Why is the RCA the best art and design school in the world?

The Royal College of Art has been named the world's best art and design school for a second year in a row

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Synonymous with extreme wealth and the British establishment, if the London borough of Kensington and Chelsea were a person it would be a portly gentleman in finest white tie.

The Royal College of Art (RCA) - a piece of brutalist architecture rudely positioned next to South Kensington’s ornate Royal Albert Hall – would, then, be a bur stuck to the gentleman’s silk handkerchief: an oddity bursting with the seeds of change.

Arch-modernists, pop artists and Young British Artists (YBAs) are among the school’s alumni, who have consistently pointed a finger at the establishment, curled that hand into a fist to break into the mainstream, and forced society to question how it views itself.

For the second year in a row, the RCA has been named the top art and design school in the world by the prestigious QS World University Rankings, beating 1,376 other institutions.

“The RCA is a worldwide institution. It’s so known and respected, it almost needs no introduction”, says Cherie Federico, director and editor of arts and culture magazine Aesthetica.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, art schools followed the atelier model, where students were taught by a maestro, or master.

“The RCA is no exception in adopting a more inclusive approach that acknowledges that one of the greatest resources students can draw upon is their peers,” explains RCA rector Dr Paul Thompson.

Radical from the start, the RCA started life as the Government School of Design in 1837, before taking the step to accommodate art students into the same faculty in 1851.

The school expanded again in the 1960s, receiving a Royal Charter in 1967.

“The ideals set out in RCA's Charter of Incorporation in 1967 remain at the heart of the RCA’s academic vision today: advancing art and design education, and creating new knowledge in art and design through research and scholarship,” says Dr Thompson.

The only entirely postgraduate art and design university in the world, students can study in one of 24 programmes available in the schools of Architecture, Communication, Design, Fine Art, Humanities, and Material.

The public is invited to view students' works not only at the end of the year but in interim shows – a rarity in art schools.

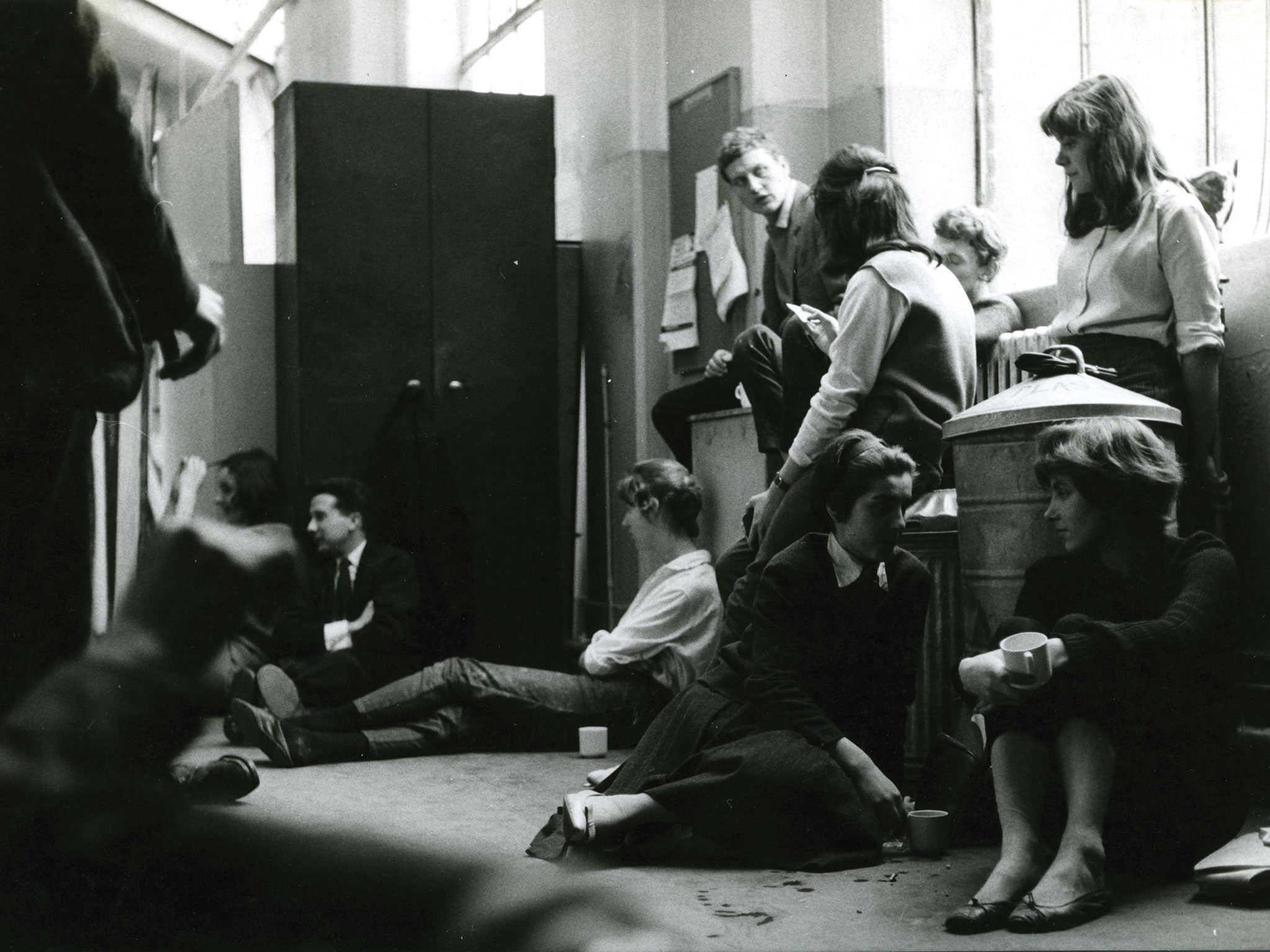

The Pop Art generation that exploded from the RCA in the 1960s is a good place to start when considering why the RCA is a world-beating institution.

That generation joined the art school after it had given birth to The New Sculpture movement, of which Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore were defining figures.

Creating art that flaunted the vibrancy and gaudiness of pop culture with a sceptical eye, the pop artists shut the door on the bleak post-war era in Britain.

Among them was Derek Boshier, of the Fine Art school’s class of 1962, who would go on to create art for The Clash and David Bowie, and work across painting, film, books, and 3D objects.

He was a 22-year-old from Portsmouth and bored by national service, so Boshier tentatively applied to the school in the hope he would catch the tutors’ eyes.

At the two-day interview in London, he chatted with two other RCA hopefuls.

One of the young men identified himself as David Hockney from Bradford. “Do you think we’ll get in?” he asked Boshier.

Drawn together by their working-class backgrounds and fascination with popular culture, Boshier, Hockney, Peter Phillips, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield became friends, and later behemoths in the international Pop Art movement.

He and his provincial friends were thrilled by the excellent library, the niche film society, and the opportunity to mingle with students from other disciplines that was “not common in other art colleges”, Boshier writes in a letter of thanks to the university in 2015. Among the then-unknowns he met were designers Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell, and filmmaker Ridley Scott.

Boshier’s letter describes an environment where students unafraid to experiment, became confident with different media, and were open to thinking in new ways.

The RCA is so known and respected, it almost needs no introduction

“Those days and it [the RCA] had [a] profound influence, not only on my art, but on my life”, Boshier says.

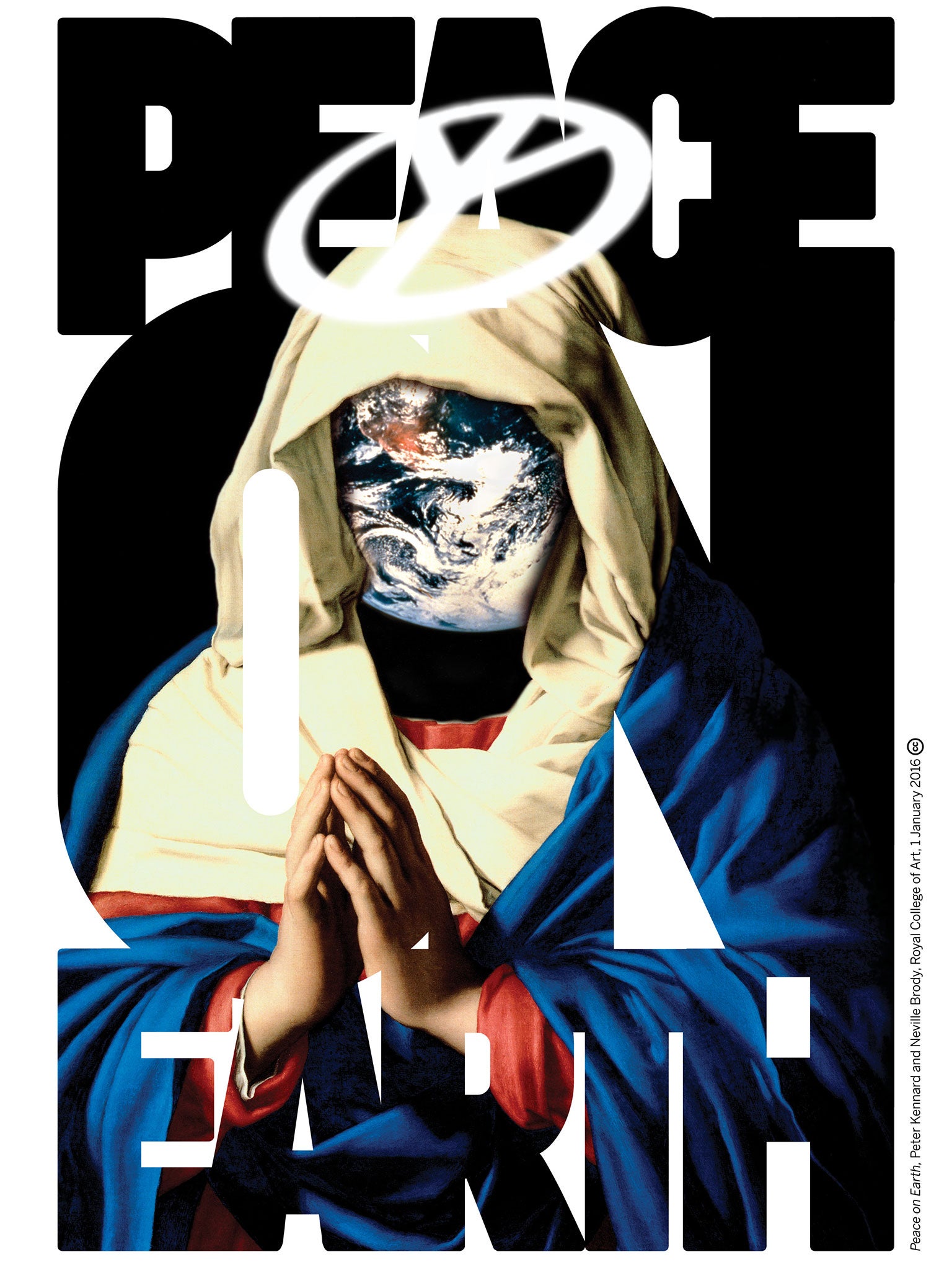

Peter Kennard, a photomontage artist known for his image of Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of a blazing Iraqi oil field, joined the school in 1977 as a painter. He is now a senior research reader in photography, art and the public domain and a senior lecturer in photography at the Fine Art school

Exposed to other departments when he arrived, including metalwork, he later specialised in photography.

As a lecturer at the RCA, Kennard is given the freedom to work outside the school. Students are therefore taught by tutors active and well-respected in their fields. And the school's collaborative spirit means that tutors and students often work together.

Last year, Kennard, Communications Professor Neville Brody and senior publishing manager Octavia Reeve came together for a project called “Peace on Earth”.

The commitment to interdisciplinary work also enables students to work with the Victoria & Albert Museum and Imperial College, London, and masters programmes in partnership with universities in Beijing and Tokyo.

“[The RCA] is based on critical thinking. It allows people to develop their ideas not just based in the material that they originally think that they are working in”, explains Kennard, who is now a senior research reader in photography, art and the public domain and a senior lecturer in photography at the Fine Art school.

As a student, Kennard realised the school pioneered the rejection of the canon when an external examiner assessed his final degree project and questioned whether photography qualified as fine art.

“It had got through to the RCA that art was everything you named as art”, he says.

The college attracts students uninterested in the romantic notion of the artist as a pained, isolated figure, and who understand that their art has an importance beyond themselves, he says.

“[What we're looking for] is someone who really needs to make work”, he says, adding that students grow by “going back to basics”.

Acknowledging that the pop artists were important, Kennard disagrees that those were the college’s golden years. In fact, as students become more aware of the social impact of their work, art is more vital than ever, he says.

Kennard argues that Assemble, which last year became the first architecture or design studio to win the prestigious Turner Prize for art for a housing project on a council estate, exemplify how the art world is changing.

“Society couldn't exist without this creativity, and you're part of that creativity.”

Such ideals attracts some of the most talented and ambitious students in the world to the school. But the departure of senior members of staff last year put the school’s future in doubt. Is the RCA unravelling?

Cherie Federico doesn’t think so.

“With a 180-year history, I do believe that the RCA will survive.”

“I think especially in recent years the RCA has responded very well to the changes in art in design.

“The courses on offer reflect a true understanding of the current developments.”

To push the school forward, Dr Thompson will focus on continuing innovation. In the next decade, the RCA will open new research centres in design and computer science; in design and material science; in 'intelligent mobility' – or driverless vehicles.

“The most fruitful and exciting areas of human endeavour are currently occurring at the crossroads between art, design and the sciences,” he says.

“We want to encourage artists and computer scientists, designers and material scientists to collaborate together in addressing some of the key global challenges of the future.”

It is clear that pressure to preserve the school’s legacy while continuing its revolutionary spirit is not lost on current students, and the collaboration and commitment to unique thinking that made it great hasn’t died.

“Knowing that so many amazing people have come from the RCA is an inspiration, and being part of such a historical institution is humbling,” says Josie Tucker, a designer studying at the School of Communication.

“One of our tutors said once that students are chosen because the tutors want to work with them, and like them as people.”

Emma J Shipley, who has launched her own luxury clothing and accessories label since graduating with an MA in Textiles in 2011, says the most important lesson she learned there was to “follow your own path, to find out what is unique about what you do. To do everything with soul.”

She sums up her experience at the RCA in three simple words: “Intense, unique, magic.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments