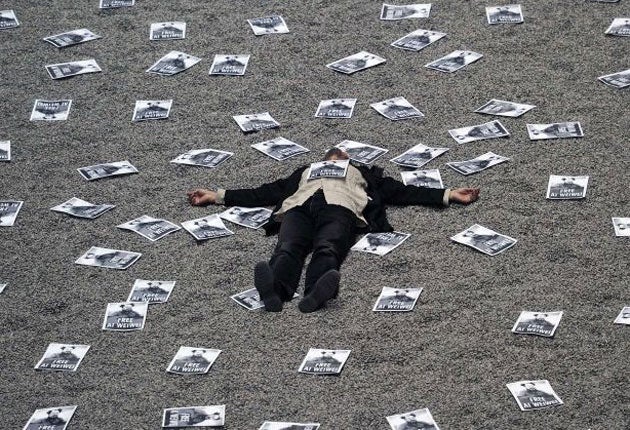

People power: It's the taking part that counts

The jailed Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei is part of a new cultural movement that's using people power to challenge society's vested interests

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 12 May 2008, an earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale shook the Chinese province of Sichuan. Among the dead were thousands of children whose schools – shoddily built as a result of corruption – collapsed around them. Despite widespread anger and grief, government officials refused to investigate the disaster fully.

That was when the artist Ai Weiwei stepped in to launch his own inquiry, organising 200 volunteers to go door to door, talk to bereaved parents and record details of their deceased children online. "Everybody knew something was wrong, but nobody knew any facts or looked carefully to find the names of the children who died, which school they were in, at what level, how old they were, female or male," said the artist, whose volunteers eventually uncovered the names of over 5,000 pupils. "Whatever we found out, we posted on the blog. That caused a revolution in the minds of the people."

In the outcry surrounding his arrest by the Chinese government last month, it's sometimes hard to make out exactly what kind of artist Ai Weiwei is and why his work is so lauded by supporters and treated with such suspicion by Chinese authorities. We know him as a trenchant critic of the Chinese state. And we have seen the Sunflower Seeds, albeit from behind a barrier. But we're unsure about the connection between the two. Especially because the commonly applied description of him as an artist and activist suggests his artworks and his politics run on parallel tracks.

Yet the key to the kind of artist he is – and what makes him such an incendiary figure to his government – is the fact that, for all practical purposes, there is no distinction between his personal life, his art and his political principles. An exercise like the Sichuan campaign is, for him, as much of an artwork as any of the more formal experiments in photography, sculpture or architecture he has carried out over the years. As, come to that, is his prolific use of Twitter – he has over 80,000 followers and, pre-arrest, would sometimes post comments dozens of times in a day – and the films of his everyday life he uploads to his YouTube channel.

What's common to all these activities is his desire to reach beyond the cloistered environment of a gallery or a museum and connect with ordinary people about real social issues. And a belief that, in doing so, art can trigger political awareness. Referring to the work of Marcel Duchamp, who famously bestowed the status of art on commonplace objects like a bicycle wheel and a urinal, Ai has talked of subjecting the repressive environment in China to the same process of artistic transformation. "I take the political situation in China as a ready-made. I transform it in my own way to show people the possibilities of this reality and a way to change. That, I think, is directly related to my art; it's the same thing to me."

Ai Weiwei is not alone in the conviction that artistic projects carried out in public with the participation of ordinary people can trigger meaningful change in society. Across the course of the past decade a growing number of artists have eschewed the physical business of painting or sculpture in favour of working with the public to create moments and experiences of heightened social or political awareness. They include significant British figures like Jeremy Deller and, with his Fourth Plinth project for Trafalgar Square, Antony Gormley. And respected international names like Francis Alÿs, Thomas Hirschhorn, Carsten Höller, and of course Ai Weiwei himself. The result has been ambitious, strikingly imaginative artworks that have corralled hundreds, even thousands, into action while asking sometimes searching questions about the state of culture and society.

Well-known projects include Deller's The Battle of Orgreave, a restaging of a pitched conflict between miners and police at the height of the miners strike in 1984, played out 17 years later with members of English civil war reenactment societies. For Francis Alÿs's epic When Faith Moves Mountains, the Belgian artist recruited 500 Peruvian volunteers to shovel a gigantic sand dune on the outskirts of Lima, shifting its position an almost imperceptible four inches, in a commentary on the halting progress of Latin American government and civil society. And, invited to take part in the prestigious Documenta festival in Kassel, Germany in 2007, Ai Weiwei arranged for 1001 volunteers from across China, none of whom had ever left the country before, to visit the town and wander freely for eight days. Ostensibly a mass excursion, the trip took on a more pointed resonance when read in the context of questions of migration, globalisation, the use of labour and the role of the individual in China.

In addition, there are a considerable number of socially engaged works by less high-profile artists. Among these are the all-day disco-dance marathon for teenagers in Ramallah staged by Turner Prize nominee Phil Collins; Polish artist Pawel Althamer's relationship with a group of adults with mental and physical disabilities in Warsaw, who have been both the subject of his work as well as his collaborators; and the floating abortion clinic designed by Dutch group Atelier Van Lieshout that is operational in international waters.

Diverse as these projects are, they share a number of common features. They are staged outside a gallery. They are hard to classify: are they performances, durational works, popular spectacle? And they are reliant for their success on the enthusiasm and involvement of the public to bring an artist's ideas to life.

The emergence of this participatory art movement has attracted major attention in the art world. It was the subject of a group show, The Art of Participation, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2008. Next year's flagship commission in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall will feature the British-German artist Tino Sehgal, who creates what he calls "constructed situations" between performers and ordinary people. And the influential critic Claire Bishop has said of leading lights such as Deller and Höller that "their work arguably forms what avant-garde we have today: artists using social situations to produce dematerialised, anti-market, politically engaged projects that carry on the modernist call to blur art and life."

If this is a new avant-garde then it's operating on a different set of aesthetic rules to previous generations of political art. Typically, artists have wanted us to be as outraged as they are in the face of war or great injustice. Their pictures – angry, provocative, shocking – reflect this. Think of Picasso's Guernica; the shrieking heads and spewing blood in the imagery of feminist artist Nancy Spero; Richard Hamilton's Bobby Sands, naked beneath a blanket in his befouled cell at the height of the dirty protests.

By contrast the likes of Deller and Alÿs prefer dialogue to polemic. Rather than conjuring visceral imagery or bludgeoning slogans they wield art as a form of "soft power": a means to bring people together, to stir emotions and nudge participants towards a new understanding of the social and political order.

The rising prominence of their work also sits in contrast to the glitziness of the pre-financial crash art market, when top sellers like Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons were being snapped up by an international moneyed elite, eager for trophies that affirmed their wealth, not critiqued it.

The irony is that, if ever there was a time for art to challenge and provoke it should have been during the past decade. September 11, the War on Terror, yawning inequalities between rich and poor and North and South, the failure of the Copenhagen climate talks – these have been troubled years. Yet you wouldn't have known it from wandering through most galleries, where the accent was firmly on commerce not conscience.

But in its attempts to more deeply consider the condition of society, participatory art raises questions of its own. Are participatory projects really classifiable as art or are they closer to a form of applied social work? And, if we accept them as the former, is it anyway possible for art to effect the kinds of transformation purported? Is it possible for art to change the world?

Champions of the genre, like the French critic Nicolas Bourriaud, describe the virtues of the movement in utopian terms, as an opportunity to create occasions when people can meet, establish bonds of trust and cooperation and to, as a consequence, begin looking at the world with new eyes. As he puts it, this is art as "a state of encounter".

That rings true with regard to Deller's recent road trip across America towing a bombed-out car from Baghdad. Pitched up in town squares, the car's presence triggered heartfelt conversations among local people about the rights and wrongs of the Iraq war and America's place in the world, post 9/11.

But the outcome of such encounters is perhaps less certain with a figure like the New York-based Rirkrit Tiravanija, who's chiefly known for staging exhibitions that consist of him cooking Thai food for gallery-goers.

Maybe the question to ask then isn't if participatory art can change the world, but whether it succeeds in transforming our perception of the world and our place within it. The current, uncertain fate of Ai Weiwei highlights the heavy personal cost that can result from merging art and politics in this way. The artist's words, speaking about his Sichuan campaign, make clear what the worth of doing so might be. "This investigation will be remembered for generations as the first civil rights activity in China. It directly affects people's feelings and their living conditions, their freedom and how they look at the world. To me, that is art."

Ekow Eshun was the director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts from 2005 to 2010

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments