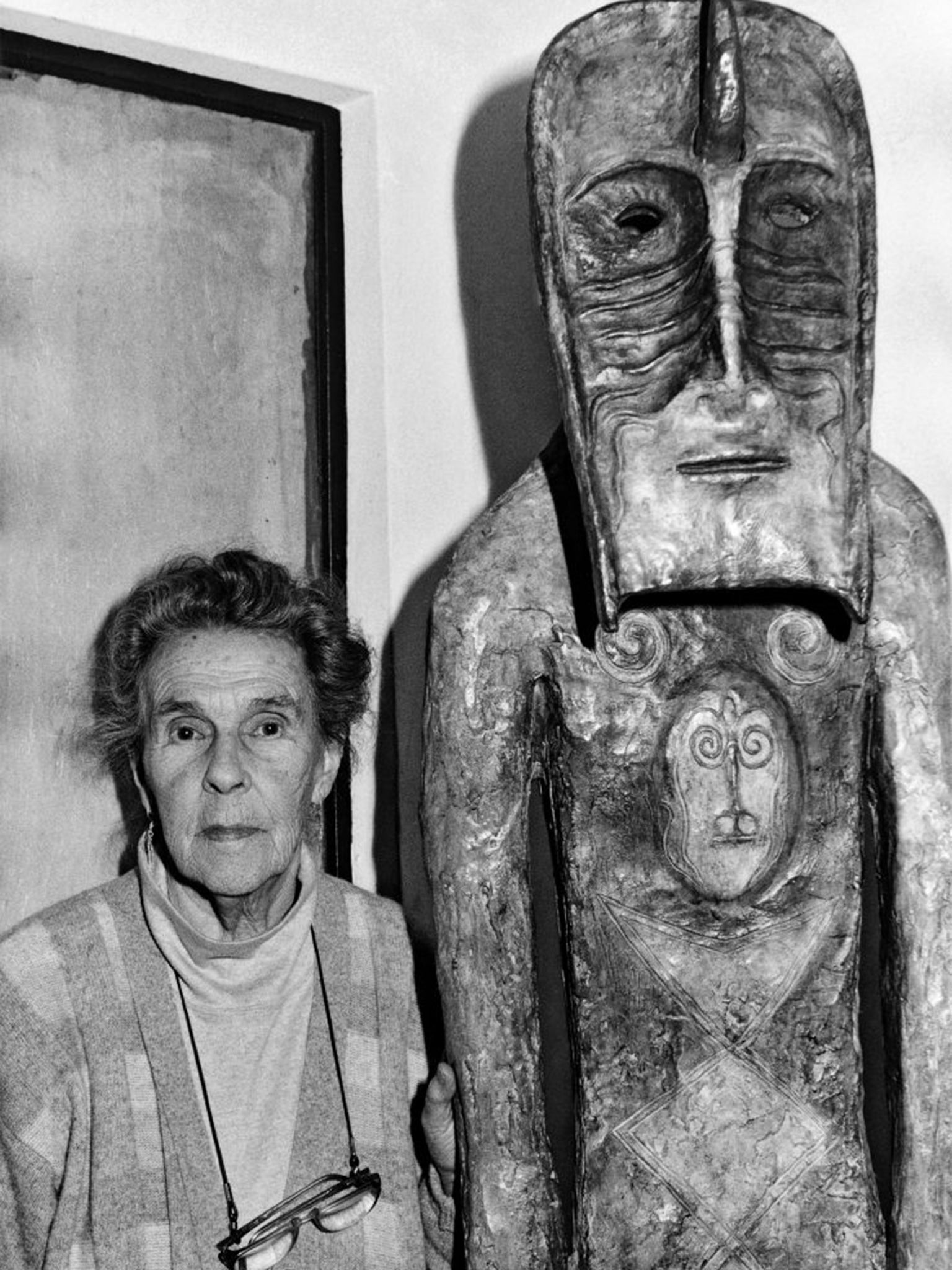

Leonora Carrington transcended her stolid background to become an avant garde star

Leonora Carrington revolted against her bourgeois background in Thirties Lancashire, eloped to Paris with Max Ernst and became a record-breaking Surrealist artist. Ahead of a new show at Tate Liverpool, Boyd Tonkin tells the story of a remarkable woman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The life of Leonora Carrington can sound quite as surreal as her art. Presented to Queen Mary as a debutante in 1935, this Lancashire industrialist's daughter became, 70 years later, the most valuable living Surrealist when her Juggler painting sold for a record price. The child of textile wealth she would elope with Max Ernst and later, in Mexico City, join a multi-talented circle of artistic émigrés. In 1963, this visionary fabulist was commissioned to paint an epic mural of Maya mythology for Mexico's National Museum of Anthropology. At home, she kept her revered boxes of PG Tips tea under lock and key.

Carrington's 94 years of upheaval and re-invention (1917-2011) added an improbably colourful chapter to the history of modern culture. She wrote as well as painted, publishing short stories, a novel (The Hearing Trumpet) and a devastating memoir (Down Below) of the wartime breakdown that preceded her flight from Europe to Mexico. However, her art – from paintings and murals to stage designs, sculptures and costumes – stands at the heart of her vision. Drawing on Celtic, Catholic, Jewish and Mesoamerican legend, lore and ritual, it weaves these mingled sources into an ecstatic, enigmatic bestiary.

Hybrid creatures, chimerae from hallucinations that tremble on the edge of nightmare, surge from the depths of some collective unconscious, objects of dread and of desire. They throng scenes in which vegetable, animal and human forms morph from one state to another. Via this fantastic zoology, Carrington fashioned what she called her "personal geography". When she was 20, André Breton – the pope of the Surrealist movement – first saw her art in Paris. "Quel desir d'extravagance!" Breton enthused. That extravagance, along with the discipline to give it an ever-changing shape, persisted through her almost seven decades in Mexico.

Co-curated by the writer Chloe Aridjis, a family friend from Mexico City, a major solo show of Carrington's work opens at Tate Liverpool on Friday. One of its highlights will be the Magical World of the Mayas mural, travelling abroad for the first time as a taster of the cultural exchanges that will punctuate the Year of Mexico in the UK in 2015. Aridjis has also uncovered smaller works from private collections, such as the unearthly papier-mâché masks that Carrington devised for a production of The Tempest.

As Aridjis notes, "these masks are some of the few survivors of her theatre collaborations. And the fact The Tempest is about enchantment (and disenchantment) is very fitting." To coincide with the Tate exhibition, Serpent's Tail has published Leonora by the eminent Mexican author Elena Poniatowska: a biographical novel, half-dream and half-documentary, by a close friend of the artist.

Chloe Aridjis's parents knew Carrington, and on Sundays they would often visit her house in Colonia Roma for that sacred tea. "My first impression," Aridjis recalls, "was of a formidable woman from another era, wise and somewhat mischievous. She was extremely intuitive, and nothing slipped her attention. She watched everything like a cat."

As for her art, "I was familiar with Surrealism but her paintings went beyond what I'd seen in museums in Europe. They were much more layered and mysterious and mesmerising." Although Aridjis remembers "something distinctly English about the space" of the house, which even had photos of the royal family taped to cupboards, she feels that "in some respects, Leonora was a foreigner wherever she was". Nonetheless, "she seemed very much at home in her house in the Colonia Roma".

Leonora's long, strange trip had begun in rebellion against the cramped horizons of new money in Lancashire. She studied art in London, where she met Max Ernst. By 1938, she had conquered Surrealist Paris, and the (married) Ernst himself; the couple presided over a creative menage at Saint-Martin d'Ardeche in southern France.

War brought Ernst's arrest, fractured their partnership, and propelled Carrington first into psychosis, then a medication-induced delirium. After a cloak-and-dagger escape from a clinic in Spain and a marriage of convenience to the Mexican diplomat Renato Leduc, she found refuge and recovery in Mexico City. At their home, she and her second husband – the Hungarian-born photographer Chiki Weisz, with whom she had two sons – gathered an exiled community of artists that included Remedios Varo, Luis Buñuel and her patron and fellow-Surrealist, Edward James.

Aridjis considers Carrington "one of the greatest painters of the dreamworld, and the unconscious: its landscapes, its inhabitants, its foreign language. I also think she was one of the most authentic artists of the 20th century, someone who created an utterly unique personal universe."

She hopes that the Tate survey "will put her on the map once and for all". If she had to select just one favourite work from the exhibition, which would it be? "I think it would be And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur: for me, it's one of her most stunning and enigmatic creations. All kinds of species are depicted (human, canine, minotaur, and the minotaur's petal/butterfly-faced daughter), and they're taking part in a ritual of divination with crystal balls. Like much of Leonora's work, its world is in a state of transformation".

Leonora Carrington, Tate Liverpool (0151 702 7400) 6 March to 31 May. 'Leonora: a Novel' by Elena Poniatowska (translated by Amanda Hopkinson) is published by Serpent's Tail (£12.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments