Leonora Carrington: The most dramatic moments of the Surrealist's remarkable story

After Carrington fled her aristocratic family, her extraordinary exodus would take in lunch with Man Ray in Cornwall, drinks with Picasso in Paris, confinement in a Spanish asylum and a daring escape from Hitler, before she fled to a new life in Mexico. Ahead of a major Tate exhibition, the Surrealist’s cousin, Joanna Moorhead, recalls the sentimental five-year journey she spent taking in the painter’s footsteps

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The traffic is solid at 3pm on a July day in 2011 in Tacuba, Mexico: the exhaust fumes are relentless, the air is grey. It's the same old story, the story known only too well to Chilangos – residents of Mexico City – and regular visitors. I'm in a taxi edging along a three-lane highway, I've been in the car for an hour, and it's just beginning to dawn on me that the driver is even more clueless than I am about where we're going. "Panteon Britanico?" British cemetery? I ask again, wearily. "Usted sabe?" You know?

"Well, what did you expect? This is Mexico, remember?" That's what Leonora would say, if she were here now. She would raise her eyebrows and give me an exasperated look. Mexico is all about chaos and adventure and the unexpected. Some call it surreal; the poet André Breton called it the most surreal nation on Earth when he visited here in the 1930s. But I never heard Leonora, the last of the Surrealists, call her adopted country surreal. Mostly, she thought it was funny: we laughed about it, a lot.

But I'm not laughing today. I'm frustrated. Leonora isn't with me in this taxi, because she's dead. She died two months ago, in May 2011, and this is my first trip back to the city where she spent the bulk of her life, the city where I've been visiting her regularly for the past five years. I'm trying to find her grave. I want to say goodbye.

Lambe Creek, Cornwall, 1937

We're on holiday, and I've persuaded my husband and our children to make a detour. "Oh Mum, it's not about Leonora again, is it?" they moan. Everyone knows I've become a bit obsessed with my exotic cousin since I got to know her in 2006. So here we are, driving down the narrow, hedge-fringed lanes south of Falmouth. We're looking for Lambe Creek, which is tucked away on the southern shore of the river Truro. It turns out to be a handsome, whitewashed house (now a private residence, so we cannot look inside), with an ancient church nearby, and a good pub over the water at Malpas.

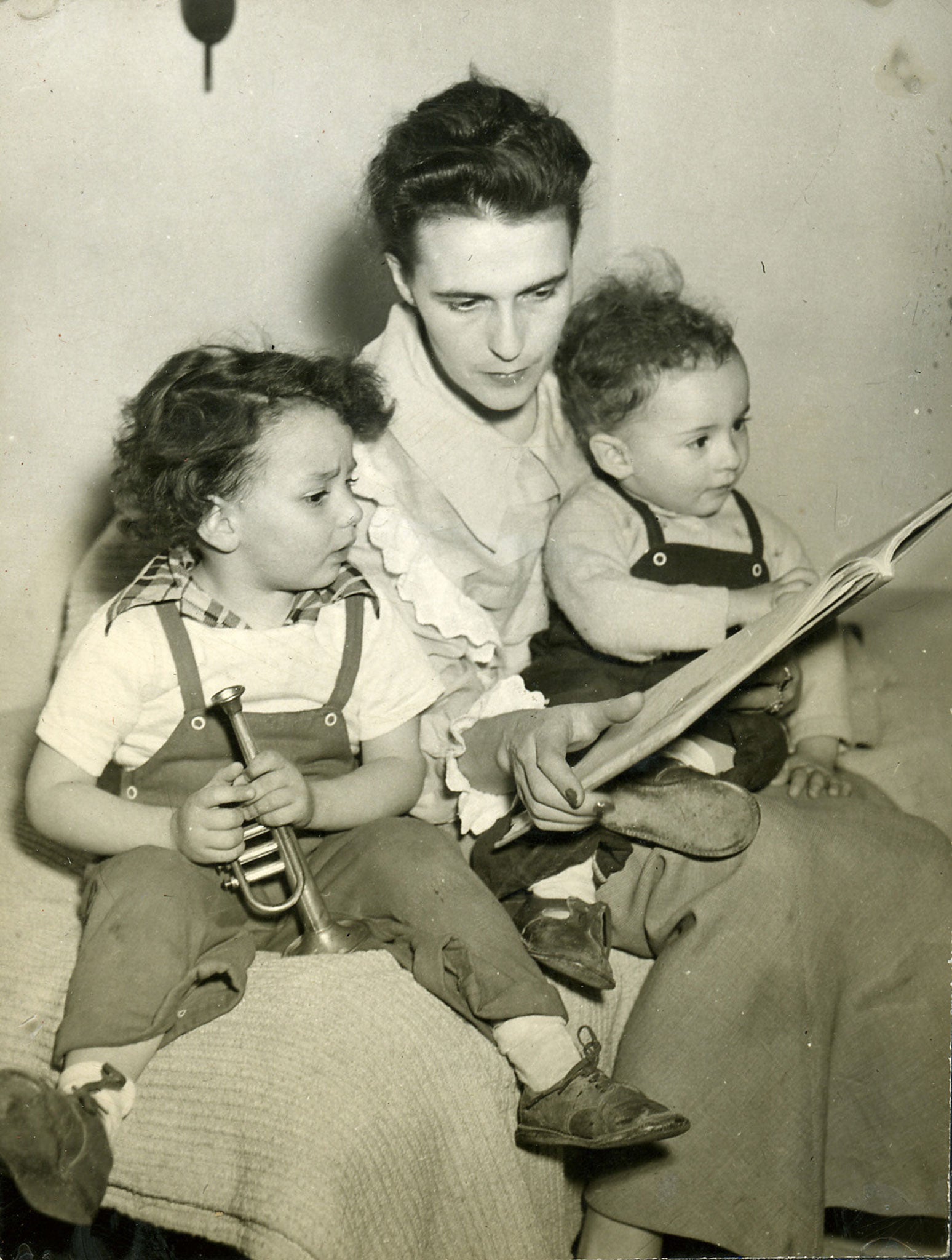

The 20-year-old Leonora and her lover Max Ernst visited the church, and they drank in the pub. It was 1937, and they were hiding, on the run from Leonora's father, Harold, who, incandescent at his daughter for eloping with a married artist almost his own age, rather than bagging herself an aristocrat during her debutante season, was trying to have Max arrested. His paintings, he told the police, were pornographic.

The couple spent three weeks in Cornwall, surrounded by some of their greatest friends: Lee Miller, Roland Penrose, Man Ray, Paul and Nusch Éluard, Eileen Agar. Henry Moore joined them one day for lunch. Another day they all signed a postcard to Éluard's ex-wife Gala, now living with Salvador Dali in Paris. Love was like that, for the Surrealists.

For Leonora, who had been raised in our financially advantaged but culturally impoverished family, the weeks spent in Cornwall were her inauguration into freedom, her first experience of an existence that wasn't bounded by the narrow expectations of her clan and her class. A new and fascinating world was starting to bud, a world with wide horizons and books and art and, more than anything, ideas, and she was rushing towards it with both her arms open wide.

Café de Flore, Paris, 1937

It's a sunny lunchtime and I'm having a glass of wine at one of the busiest cafés in St Germain. We're jammed in like sardines: this is the place to see and be seen, just as it was when Leonora sat here and raised her glass to her lips, back in the winter of 1937. She had left England, for ever as it would turn out, a few weeks earlier: left her family (happily), left her inheritance (she wasn't always so pleased about that), left her predictable, cossetted future (nothing delighted her more). And now she was free, in France with Max, and at the centre of the Surrealist group that included Picasso, Duchamp, Dali, Breton and Leonor Fini (Leonora would never forgive me listing only male artists and omitting one of the less famous but hugely talented women among them).

But there was a problem: Max had a wife, Marie-Berthe, living in Paris. One night she followed them to the café, told them she would never let them be together, and threw a few cups and plates at Leonora before leaving. At the Café de Flore, where passion was as much a feature of the menu as champagne and canapés, I doubt if anyone batted an eyelid.

Saint-Martin-d'Ardèche, 1940

My friend Catherine and I are swimming in the river in the Ardèche in the South of France at 7am. Leonora used to do this; for a while, she and Max camped on its banks. This was their escape from Paris, their hiding place from Marie-Berthe. They had no money, but eventually Leonora's mother, Maurie, sent some cash, and the couple bought a farm on a hillside. Later that day Catherine and I visit it. The place is eerily intact, almost exactly as it was on that day in 1940 when Leonora decided to flee, leaving behind Max, imprisoned as an enemy alien.

The house she left was imbued with their story: they had painted the walls with their love, impaled it on the stairposts, carved it into the cellar floor. As a hidden Surrealist treasure trove it was remarkable; but as the legacy to a great romance it seemed more extraordinary still. And this was the romance that made Leonora, the love that shaped the artist she became.

All her life she fought against being defined by her affair with Max; perhaps she might even have stayed with him if she hadn't begun to sense the same veil of constraint she had first encountered in her childhood. Leonora wasn't a woman who was going to be suffocated by anyone: not her family, and not her lover either. Staying with Max would have clipped her wings. Freedom always was her guiding star.

Santander, 1940

It is the school holidays, and I have brought my daughter to the beach. One day we get a bus to a park on the edge of the town. Miranda, 12, is bored by its vast, rolling, green grassiness. Near the road there is a gate and a little stone grotto.

I have never been here before, but I already know this place. Leonora drew a map of it: "Down Below", she called it. This was the scene of the hardest time in her life, a time she struggled to talk about even 70 years later. This is where she was incarcerated in the mental hospital that once stood here, and where she was tied down and injected with a drug that brought on fits. It terrified her – yet the thought of that dreary, monied, pampered future in England terrified her more.

She refused to go when my great-aunt and uncle sent the nanny in a warship to bring her home. They were that kind of family; one thing the art historians have taken a long time to twig is that, conventionally uncultured though our family undoubtedly was, the surreal had its roots far further back in Leonora's life than her meeting with Max. It was the most terrifying place she had ever known, but when the offer of safety came, she dug in her heels and stayed put.

Lisbon, 1941

It's February in the Portuguese capital, but the pastel-coloured city is bathed in warm, bright sunlight. I'm standing outside the house where Leonora lived in 1941, at the top of a hill, and looking down at the rows of huge, ocean-going liners in the harbour below. She would have done this, too: she would have hoped, day after day, that the time would come when she had a ticket to board one of them, to escape from Europe and Hitler and her family and everything she was desperate to get away from.

By this stage she had her passport, in the shape of a Mexican diplomat called Renato Leduc. Picasso had introduced her to him, back in Paris: they had met again in Madrid, after she escaped from the asylum. They had a few drinks together; she told him her story. She was on the run: no money, no family, no direction. She had left her lover and she had run out of friends. Renato raised his glass, smiled at her over it, and gave her his solution. "Marry me," he said.

But there was one more twist. Walking in the refugee-strewn city one day, Leonora saw a familiar figure: Max Ernst. He had gone to Marseilles and met the wealthy art collector Peggy Guggenheim, who quickly fell head over heels in love with him. Max spotted his exit visa. As a Hitler-hating German, Europe in the early 1940s was an increasingly dangerous place for him, and he and Peggy hurried to Lisbon, "the great embarkation point" as it's described in the movie Casablanca.

Max adored Leonora, and seeing her again was devastating for him: Peggy knew that, and writes about it movingly in her autobiography, Out of this Century. But as for reigniting their affair – forget it, Leonora told me. "You can't imagine how terrifying it was, how desperate we were to leave." Part of Max would always belong to Leonora, and part of Leonora would always belong to Max; but a future together was impossible. Max and Peggy left first, by Pan Am clipper. A few days later, Leonora and Renato departed by ship. Leonora's European odyssey was over.

Mexico City, 1942-2011

Unexpected things happen all the time. I didn't expect to meet my father's cousin, who had disappeared from our family 70 years earlier and who had hardly ever been heard from since; I didn't expect the mapless taxi driver to find the cemetery. But just as I was about to give up, there we were, turning into the gate, driving along past the rows of gravestones dotted with flowers and photographs, parking in the far corner towards the back where Yolanda, Leonora's housekeeper, had told me I would find her grave.

"Like a strong, blinding light of imagination you came, and you left us," say the words on her stone. I left my flowers; I shed my tears. But most of all I thanked her for showing me how to live; how to embrace life; how to be brave (she always worried she wasn't brave, but perhaps that's the hallmark of those who truly are); how to be true.

My relatives had warned me that when I first came to Mexico to find her she wouldn't welcome me, wouldn't let me in, didn't want her family back in her life. But it turned out that she was simply waiting for us: we had to come to her, not the other way round. And now, because I did come to her, I have a little part of her in my heart for ever. I cherish it, and I am proud to carry it there.

'Leonora Carrington' is at Tate Liverpool (tate.org.uk) to 31 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments