From Da Vinci to Degas: How famous artists were affected by their eyesight

Degas suffered failing vision from 1860 to 1910, with his style becoming increasingly rough as his eye disease progressed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Was Leonardo Da Vinci’s genius helped by a vision disorder? That’s certainly what new research suggests.

Analysis of the Renaissance painter’s face from paintings, drawings and sculptures have revealed he may have suffered from a squint – known medically as a strabismus.

Da Vinci is believed to have suffered from a type called intermittent exotropia, a condition which causes one or both eyes to turn outward and affects around one in 200 people.

Researchers have suggested that the disorder may have helped him because it would have given him the ability to switch to monocular vision, in which both eyes are used separately, and allowed him to focus on close-up flat surfaces.

“It is hard to tell which eye was affected from the paintings,” visual neuroscientist Professor Christopher Tyler says. “But it would have been particularly useful for getting the whole scene geometrically correct.”

His study, published in JAMA Opthalmology, saw him scruitinise surviving images of Da Vinci – of which there are very few. They included he Vitruvian Man sketch and the bronze sculpture David, reputedly a depiction of the young Da Vinci.

In all cases, the eye misalignment was measurable, though not severe and averaged a -10.3 degree deviation from the focused eye across the six pieces. The negative number means that the eye would typically look outwards (exotropia) and Professor Tyler argues that Da Vinci’s strabismus may have been non-existent when focusing intently on an object, but would come in when he relaxed into painting – giving him the best of both worlds.

“The weight of converging evidence suggests that Da Vinci had intermittent exotropia, with a resulting ability to switch to monocular vision,” he said. “This would perhaps explain his great facility for depicting the three-dimensional solidity of faces and objects in the world and the distant depth recession of mountainous scenes.”

Multiple studies published over the past four or five decades have assessed how eye conditions have changed the work of great painters in their later lives, most notably those of Dr Michael Marmor, author of several books on the subject.

Here are some of the most prominent artists whose work was affected by their eye conditions.

Degas

Degas suffered failing vision from 1860 to 1910, with his style becoming increasingly rough as his eye disease progressed.

In 2006, Dr Marmor concluded that his central vision, where acuity is sharpest, had weakened in his later years. As it grew blurry, his painting style became more coarse, losing the refinement of his earlier work.

Mamor suspected that his later work looked smoother and more natural to Degas than it does to viewers with healthy eyes, because it was filtered through his own visual pathology.

Rembrandt

In 2004, neuroscientists Margaret S Livingstone and Bevil R Conway, both then-students at Harvard Medical School, observed that the 17th-century Dutch painter’s eyes were often misaligned in his self-portraits, so one appeared to look directly at the viewer, while the other looked off to the side.

Livingstone and Conway believed that, assuming Rembrandt had painted himself with unforgiving accuracy, he had poor stereovision – which could have been advantageous as he would have struggled to see depth with stereoscopic cues.

Stereo blindness, or the inability to use the horizontal shift between our eyes to allow us to see in 3D, can aid artists painting in two dimensions.

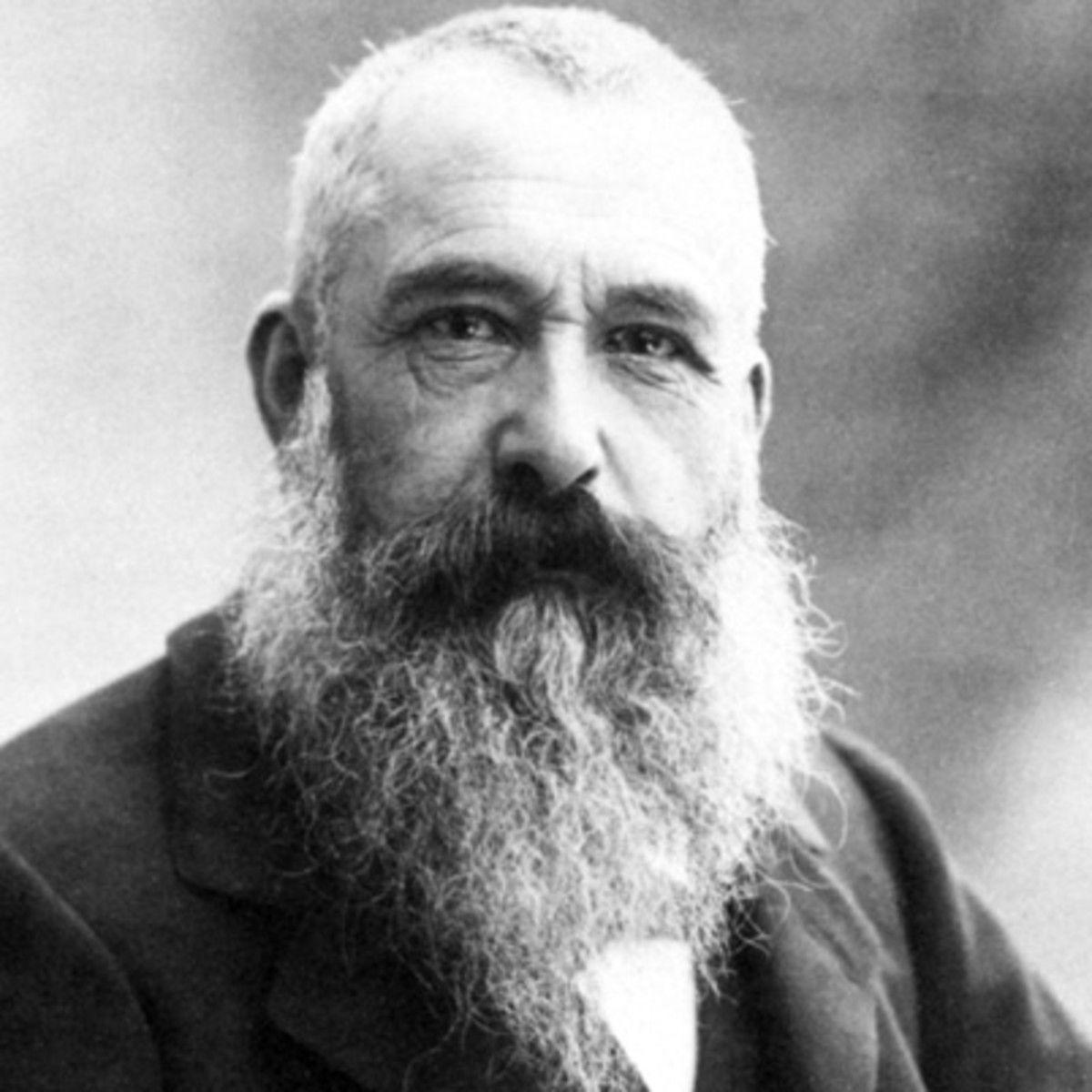

Monet

Claude Monet wrote about his growing frustration with his declining vision in 1914, noting that colours no longer had the same intensity.

“Reds had begun to look muddy,” he wrote. “My painting was getting more and more darkened.”

After undergoing cataract surgery in 1923, Monet was able to return to his original painting style, and even threw out much of the artwork he had completed during the 10-year period when he suffered from eye disease

Georgia O’Keeffe

The celebrated 20th-century American painter was best known for her canvases depicting flowers, animal skulls and south-eastern landscapes.

Suffering from macular degeneration – a medical condition which can result in blurred or no vision from the centre of the visual field – O’Keeffe completed her last unassisted oil painting in 1972.

However, her diminishing eyesight did not extinguish her will to create art. When she was almost blind, O’Keeffe returned to art with the help of several assistants and created favourite visual motifs from memory, and from her vivid imagination.

In 1977, the then 90-year-old observed: “I can see what I want to paint. The thing that makes you want to create is still there.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments