Knock Knock, South London Gallery review: A show about humour that’s as funny (weird) as it is funny (ha ha)

South London Gallery's new exhibit is more likely to leave visitors scratching their heads than laughing out loud

The clown dozes peacefully on the gallery floor, his flabby gut exposed. He wears a shiny red nose and an exaggerated grin. Yet there’s nothing terribly cheery about him; he’s a vision of gloom.

The clown is a fibreglass sculpture from 2002 by Ugo Rondinone called If There Were Anywhere But Desert. Friday, and is a highlight of Knock Knock: Humour in Contemporary Art at the South London Gallery in Camberwell. The show celebrates the 127-year-old institution’s reopening after a major expansion.

Visitors might come expecting gags, pranks, and laugh-out-loud moments to share on social media. But Knock Knock is more likely to leave them scratching their heads. The humour is often oblique – conveyed through irony, paradox, double meaning, and opaque cultural references.

The two-part show is staged in the spacious main gallery and in a new multistorey building across the street, a former Victorian fire station. Perched on the main gallery’s ceiling beams are a group of stuffed pigeons by Maurizio Cattelan.

Other lighthearted displays include Lynn Hershman Leeson’s image of a woman with a clock in place of a torso, Biological Clock 2, from 1995, and Matthew Higgs’ Portrait (Landscape), from 2006, an all-red canvas bearing the inscription “NO OIL PAINTING” across the middle.

The humour in many other works in the exhibition is even more elusive. Barbara Kruger’s 1988 image Untitled (We Don’t Need Another Hero) shows a chubby man peeling a banana. A sculpture by Basim Magdy is a glass basketball hoop titled Good Things Happen When You Least Expect Them, from 2010.

“Everyone is going to come here and say, ‘But that’s not funny work, and this isn’t about humour’ – and I want people to do that,” says artist Ryan Gander, who co-curated the exhibition. “For me, the best shows are the ones that, when you’re on the bus on the way home, you still think about, even if you didn’t like them.”

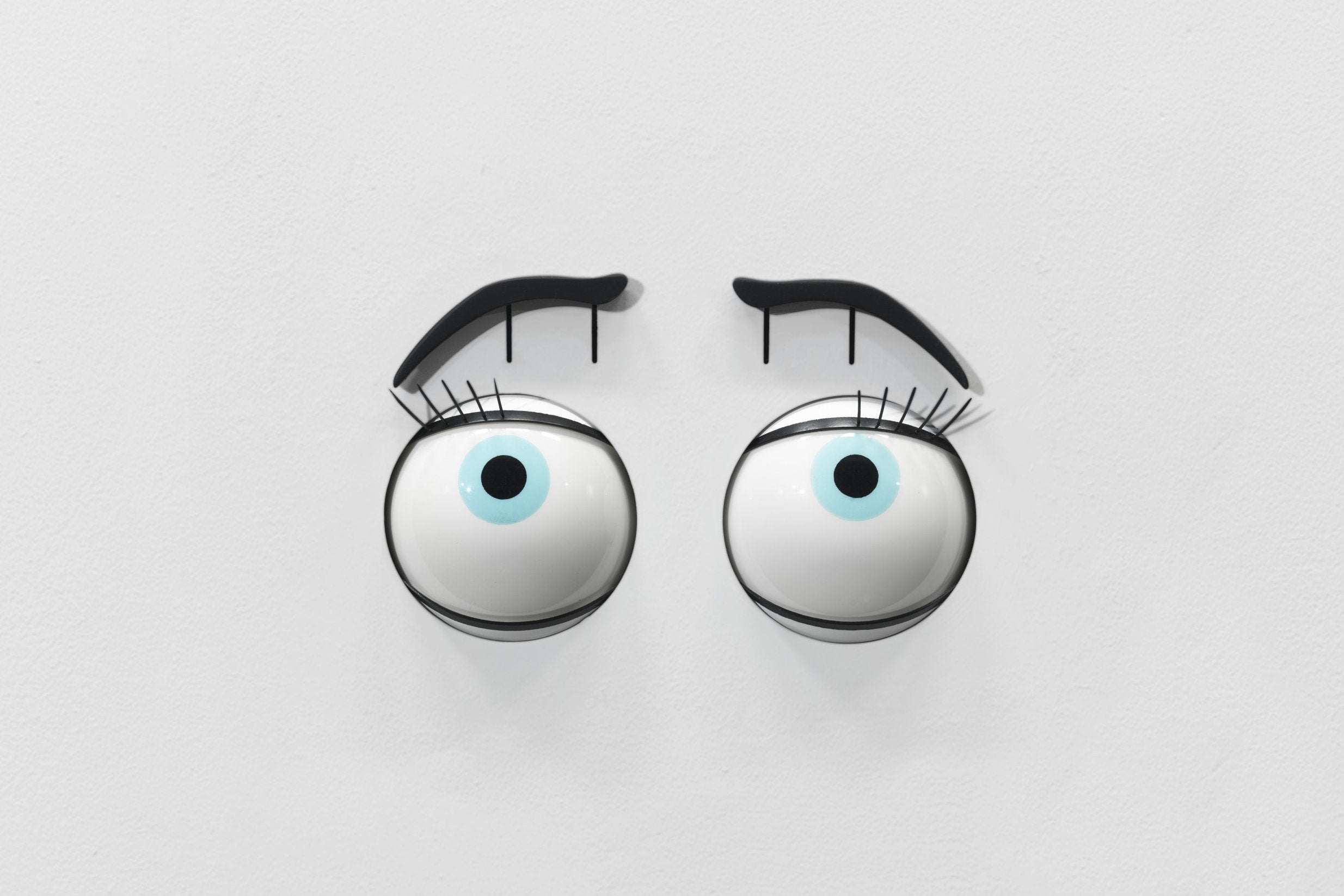

“If you curate an exhibition that makes people laugh, it’s just a theme of entertainment. This is not what exhibition-making’s purpose is,” adds Gander, who also has a work in the show: a pair of large, animatronic eyes set in the wall that react to the viewer in a manner that’s both droll and spooky.

The exhibition is “intended to be quite thought-provoking about what humour is, what makes us laugh and what doesn’t, and why,” she said. “Artists use humour as a device, as a mechanism to achieve something else, which isn’t about laughter. It’s about prompting people to think about other issues. That’s the defining characteristic running through most, if not all, of the work.”

One artist in the exhibition whose work has met with mirth (not all of it good) is Martin Creed. He won the 2001 Turner Prize after being nominated for a work that involved the lights in an empty gallery switching on and off every five seconds. It led one visitor to throw eggs at the wall and prompted The Sun to start a mock competition called the Turnip Prize.

Creed has also exhibited a crumpled piece of paper and presented videos of people vomiting and defecating. His stated aim is to make art that, like life itself, is “stupid”, or devoid of meaning or explanation. His Knock Knock contribution is a row of potted cactus plants and a wall painted with diagonal stripes.

Creed says it is not his intention to be humorous. “The problem of laughter is, it’s gone in a second. If you’re living with your own work, you can’t laugh all the time: it’s a momentary thing. If some of my work makes people laugh, that makes me happy. But to me, the worst possible thing is a person who thinks that they’re funny, or wants to be funny and isn’t. Basically, I don’t want to run that race, because I don’t want to lose the race.”

The focus of Knock Knock is contemporary art, but humour has been present in art for centuries. Hieronymus Bosch crowded his paintings with farcical-looking creatures, and William Hogarth amused the viewer with his crude cautionary tales. It became a much more important subject in the 20th century, as the author Sheri Klein explains in her 2007 book Art and Laughter.

Klein argues that the artist most directly responsible for that was Marcel Duchamp, who famously submitted a porcelain urinal to a 1917 exhibition in New York. Two years later, he presented a painting of a moustachioed Mona Lisa labelled “L.H.O.O.Q.” (which means “she’s hot to trot”, in cruder language, in French).

Decades later, pop art provoked amusement by using banal everyday items as a subject, like Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, Jeff Koons’ vacuum cleaners and Claes Oldenburg’s giant sculpture of a hamburger.

Later in the 20th century, artists used nudity as a vehicle for humour. Paul McCarthy’s Spaghetti Man (1993) is the sculpture of a standing rabbit with an elongated penis that coils like a noodle on the floor below. Sarah Lucas’s Two Fried Eggs and Kebab (1992) evokes the female anatomy by laying those foods on a table. (Lucas is in the Knock Knock exhibition with a new work titled Yves, a sculpture of a female nude made of stuffed tights.)

Despite those examples, art and humour make awkward bedfellows, Klein says, and they are not often examined together as a subject.

“There is a stigma about laughter as a response to a work of art: if it arouses laughter, then it must not be serious,” she says. Humour is also “associated with low-class behaviour. If an artist is evoking laughter, then it must mean that it’s a low-class piece of work”.

Klein says that in the immediate postwar period the United States had plenty of artists who made pun-filled, laughter-inducing art, such as the Chicago Imagists, a group of artists in the 1960s whose surrealist-inspired work made use of word plays and puns. But today, “the culture at large is a more joyless culture,” she says. “We are in a time of great pessimism: Humour is not being used as a form of resistance anymore.”

Heller says the exhibition deliberately showcased “artists you haven’t heard of or seen, or who haven’t had exposure”, rather than rolling out the usual suspects. “It’s more of an essay, going through it: a little winding journey through diverse approaches.”

Knock Knock: Humour in Contemporary Art is open until 18 November at the South London Gallery southlondongallery.org

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments