Julie Christie in Billy Liar: The girl who showed the way to the future

Some 50 years ago, Billy Liar became a cinematic hero – but, argues John Walsh, it was Julie Christie's Liz who hinted at a new way of life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British cinema of the early 1960s was a relentlessly downbeat affair, studiedly realist in a manner pinched from the French New Wave, cautiously unflashy and obsessed with failure. The key directors of the period were British intellectuals – Jack Clayton, Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger and Karel Reisz – whose chosen subjects were working-class dramas set in the provinces; not worlds with which they were wholly familiar.

The films explored British lives stuck in ruts of post-war hopelessness and looking for a way out: Clayton's Room at the Top (1958) dramatised social climbing in Yorkshire; Reisz's Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) portrayed a Nottingham machinist determined to escape a life of domestic drudgery; Richardson's The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) saw Tom Courtenay, a young bank robber, refusing to play ball with the Borstal authorities; Schlesinger's A Kind of Loving (1962) watched a Mancunian draftsman (Alan Bates) becoming trapped in marriage and domestic ennui.

Click here or on "View Images" for Julie Christie films in pictures

In British Cinema: the Lights That Failed, James Park argued that all the “kitchen-sink” movies were broadly similar, “a cycle of films with proletarian heroes who, for all their bluster, see their dreams shrivel into melancholy and their little rebellions crash to the ground. Defeat is built into the genre.” But in their midst was one movie which, while sharing the same glum subject matter, is an enduring triumph. Billy Liar features a blustering proletarian hero full of dreams – but it's altogether a different quality of film. Both its realist details and the hero's rebellion are played for comic, rather than tragic, potential. And, far from defining a world in which characters were fixed immovably, Billy Liar shows a world on the cusp of change. It's a movie that vividly heralded the Sixties world of freedom, romance and escape.

It's 50 years old this spring. A digitally restored DVD is out on Blu-ray on 6 May. It screened last week at the Bradford International Film Festival where its hero, Tom Courtenay, the festival's guest of honour received a lifetime achievement prize. There's a screening at the British Library on 26 April introduced by Michael Parkinson, a friend of Billy's creator, Keith Waterhouse, who published the original novel in 1959 and later adapted it, with Willis Hall, as a play, a musical and a TV series.

The plot concerns 19-year-old dreamer Billy Fisher (excellent Courtenay, boyish and desperate) who responds to the dullness of his Yorkshire town and his terror of being “ordinary” by telling tall stories about his parents and his circumstances to everyone he meets, and fantasising about a heroic life in his imaginary kingdom of Ambrosia. He dreams of going to London to work as a scriptwriter for an awful comedian called Danny Boon (catchphrase: “It's all happening!”) And he's uncomfortably engaged to two awful girls: Barbara, virginal, yappy and as wholesome as the oranges she obsessively eats; and Rita, a beehive-wearing harpy whose every word drips condemnation and attack. (We assume she has let Billy sleep with her and is demanding she be made an honest woman.)

In a single day, Billy must leave his job at the local undertakers, clear up a misunderstanding about missing calendars and purloined postage money, find a way to stop either fiancée from visiting his parents, then catching the train to London and a new life as a writer. But it's not that simple…

Schlesinger's camera moves restlessly through the modern townscape, noting (in the brilliant title sequence) how old urban England is being demolished, to be replaced by new styles of faceless architecture, anonymous high-rises, the coming of supermarkets, the idiocy of TV-celebrity culture. An eloquent elegy for the Old Ways is delivered by the dignified Councillor Duxbury (Finlay Currie), co-owner of the funeral parlour where Billy works. But the emergent modern world has its embodiment too, and she nearly steals the film.

It's Liz, played by Julie Christie, in her third screen role (after gamely playing unlikely girlfriends to Leslie Phillips and Stanley Baxter in Crooks Anonymous and The Fast Lady). She plays Liz, a local beauty of a kind never seen before. Though she joins the narrative in the movie's last third, we see her in a key early scene when Billy (Courtenay) tells his friend Arthur (Rodney Bewes) about her, after glimpsing her in a lorry's passenger seat. “Where's she been?” asks Arthur. “I dunno,” says Billy in admiration. “She goes where she likes. She's crazy… She works as a waitress, a typist, last year she was at Butlins – she works until she gets fed up and goes somewhere else. She's been all over.”

It's not her (vivid, glowing) beauty or her (natural, un-beehived, Bardot-ish) blonde hair that attracts him; it's her freewheeling restlessness. She's a girl who can't be pinned down and won't get stuck and, in 1963, this was a crazily unconventional position. Schlesinger celebrates it in a justly famous tracking shot, in which a long-lens camera watches Liz walking through her northern home-town, in a simple white shirt, skirt and jacket. We see her from inside shops, as she passes by, unselfconsciously swinging her handbag, smoking a cigarette, running her fingers along railings, her face smiling, grimacing at her own reflection, showing impatience at a pedestrian crossing. We watch her as an objectified consciousness: an emblem of independence.

It's a great cinema moment because she's being watched, not by Billy (who only caught a glimpse of her in a lorry) but by Schlesinger, who draws our attention to this natural beauty like someone showing off a lover. And that insistence on her life being in transit – well, a whole Sixties dream of unfettered behaviour, of hippie wandering and road movies, was about to unfold from right there.

One could argue that Kerouac and On the Road got there first. You could bring up “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”, James Thurber's 1939 story about a chronic fantasist, which is Billy's distant ancestor (it was filmed in 1947.) But Billy Liar enunciates a very specific moment in the British psyche, when a desire to escape the humdrum homogeneity of the present meets a terror of the wild freedom that beckons in the future. It's a touching drama of Hamlet-like indecisiveness amid the social comedy, the machine-gun rebellions and the dreams of victory.

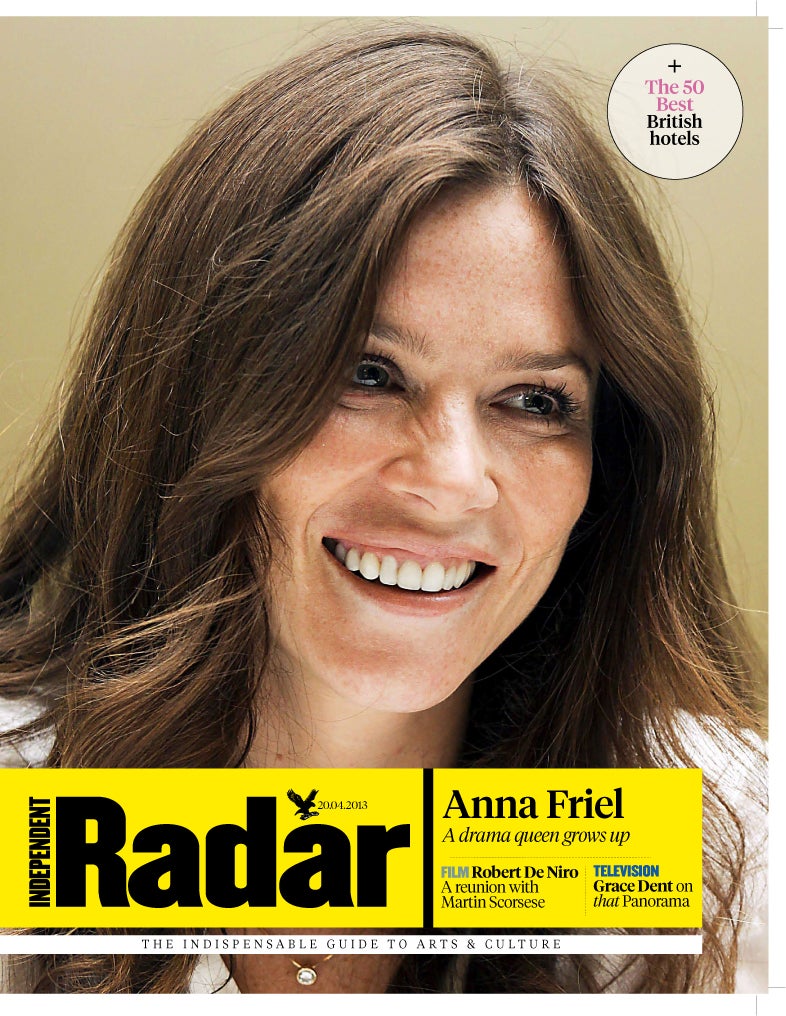

This article appears in tomorrow's print edition of Radar magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments