Jeff Koons: Paris Pompidou Centre retrospective exposes artist's shallowness and narcissism

Koons' kitsch work sells for record-breaking sums

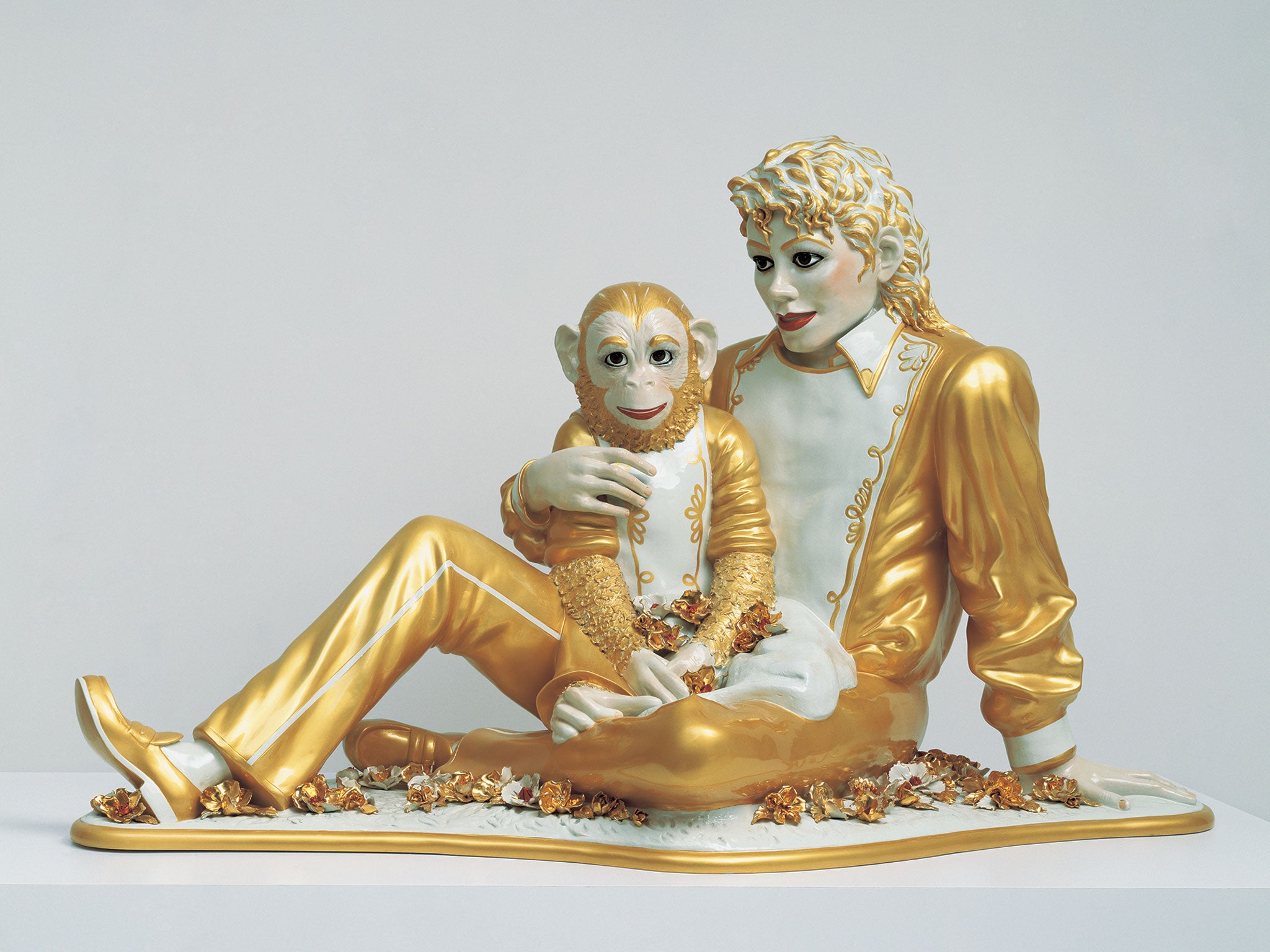

Jeff Koons’ retrospective has arrived in Paris after a critical and box-office success at the Whitney Museum in New York. Popeye, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, and the Incredible Hulk have taken up residency in the lofty galleries atop the Centre Pompidou where Bacon’s screaming Popes previously lived.

The Pompidou has unashamedly placed him next to a retrospective of Marcel Duchamp, arguably the most influential figure of the 20th century, a juxtaposition that allows the viewer to see the entire arc of Duchamp’s oeuvre – including his painting and most importantly in this context the trajectory of the ready-made, the cornerstone of Koons’ career.

Jeff Koons was born in 1955, the son of a furniture dealer who owned a houseware/ decorating shop. He studied painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He arrived in New York in 1976, selling membership subscriptions at MoMA, a job he embraced with unquestioning zeal. By the 1980s he was working on Wall Street. There has been a lot written about this period of his life, but what it shows is that the messianic Koons can sell anything.

His early work like New Shelton Wet/Dry Triple Decker (1981) involved taking ordinary household objects – vacuum cleaners and the like – and placing them neatly in towers on top of neon tubes. It’s a heady mixture of minimalism, incorporating Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, mixed with Pop art’s co-option of everyday objects. So far so good. The series Equilibrium followed: vitrines filled with basketballs in a prescient comment on the love of sport as the new religion of America.

At the same time, Koons was co-opting his signature items of knick-knacks and inflatables – symbols of bad taste or “kitsch”, a word that unsurprisingly he dislikes. He prefers the word banal. There’s a nod to Duchamp’s ready-mades in the shape of real blow-up toys and plastic bouquets of flowers placed in front of mirrors. There are several examples here. The commercial success is undeniable: Balloon Dog (Orange) recently sold for $58m, the highest price for a living artist.

What Koons had from the start was immense self-belief, and the backing of several fascinated dealers and collectors who supported his work. One of them, Jeffrey Deitch, went to the brink of bankruptcy, as he tried to get Koons’ Celebration series made.

Koons’ personal life has also played out in a spectacular fashion. In 1991 he married the porn star and politician Ilona Staller, aka Cicciolina, and fathered a son, Ludwig. At the Pompidou, his Made in Heaven series (1989-1991) is displayed in a separate room manned by a guard to prevent anyone under the age of 18 from entering. Inside, with unflinching directness, Koons portrays his couplings with Staller, transformed here into Violet-Ice (Kama Sutra) (1991), a purple glass sculpture made in Murano that leaves nothing to the imagination. The union between Koons and Staller was not long-lasting – they divorced in 1994. Koons spent money chasing custody of his son without success.

A series of blow-up pieces, including Lobster (2003), had Parisian children gasping and touching. Alarms blared as viewers were unable to resist satisfying themselves that the works were not plastic but metal, with every crease, pucker and visible seam perfectly replicated. Popeye (2009–2011), a mirrored gleaming work, is reproduced to perfection, down to the can of spinach. Koons has said, “There’s no experience or information that’s pre-required of them – the work is accessible.” If it is the intention of this art to be accessible then there is certainly a resonance with the audience here – what you see is what you get.

On the walls, paintings add little to the argument. Koons has a studio/factory employing artists as assistants to paint his works. He married one of them – Justine, with whom he has six children. Unlike Warhol’s infamously rackety factory, Koons’ is run with military precision.

If the exhibition ended here, I might have simply felt, “OK, I get it”, but the last works expose Koons’ fatal weakness: his narcissism makes him incapable of self-editing. He has talked about working in Henry J Koons Decorators, his father’s shop, and growing up in the suburbs in the Sixties where blue mirror balls were a design choice for the middle classes. The last pieces in this show are the “Gazing Ball” works from 2013, in which Koons and his studio cast sculptures from different museums in Paris, Berlin and Munich and “then nestled the gazing balls” on them. When these were exhibited in New York his gallerist David Zwirner said: “Koons says, if you’re critical, you’re already out of the game.” Evoking art history as subject matter is fair game but the placement of the balls seems deliberately ludicrous. As I look at Gazing Ball (Ariadne) (2013), with its awkward juxtaposition of classical heroine and sliding blue glass, Koons’ words slip into my mind: “I like to think of art history as putting a needle through kernels of popcorn and stringing them together”.

Luckily, art history has both more durability then popcorn, and nothing shows this more clearly then the juxtaposition of Koons and Duchamp, with a nod to Brancusi on the side. Brancusi’s reductionist sculpture Leda (1926) has reflective surfaces that prefigure those of Balloon Dog by decades; its perfection of surface relates to the infinite and indefinable.

Scott Rothkopf, the curator of the exhibition, acknowledges Duchamp’s influence on Koons: “Some people might say that Jeff is Duchamp’s greatest interpreter in sculpture, but it’s an almost perverse understanding of Duchamp. Jeff would basically spend all this time and energy to re-create things when Duchamp showed that you didn’t need to do anything other than find an object and claim it as art.” It is the choice of object that dictates success and failure. There is almost a cruelty in comparing the shallowness of Koons’ Bourgeois Bust – Jeff and Ilona (1991), to Duchamp’s erotic study of women, culminating in his magical work Etant Donnés.

Koons is now at the apex of his career. In 2007, President Jacques Chirac promoted him to the Officier de la Legion d’Honneur. A major exhibition at Versailles followed in 2008 showing his work in the grand apartments. His work is in prestigious private collections like the Prada and Pinault. His jaunty pink balloon dog has bobbed on a float down Venice’s Grand Canal. And yet, I leave this show feeling saddened.

Rothkopf says: “What he is selling is not just a painting or an optimistic dream of youth and love, but the dream of a perfect object … an extremely arduous and expensive process, and his paintings are about that, too … They are also about the people who are willing to pay for them.” Perhaps it is significant that Koons’ show at V ersailles was so successful. Is it time to have a revolution in the art world, or will we the viewers continue to be told to “eat cake”?

Jeff Koons: a Retrospective, Centre Pompidou, Paris (centrepompidou.fr) to 27 April; Marcel Duchamp: Painting Even, Centre Pompidou, ends today

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies