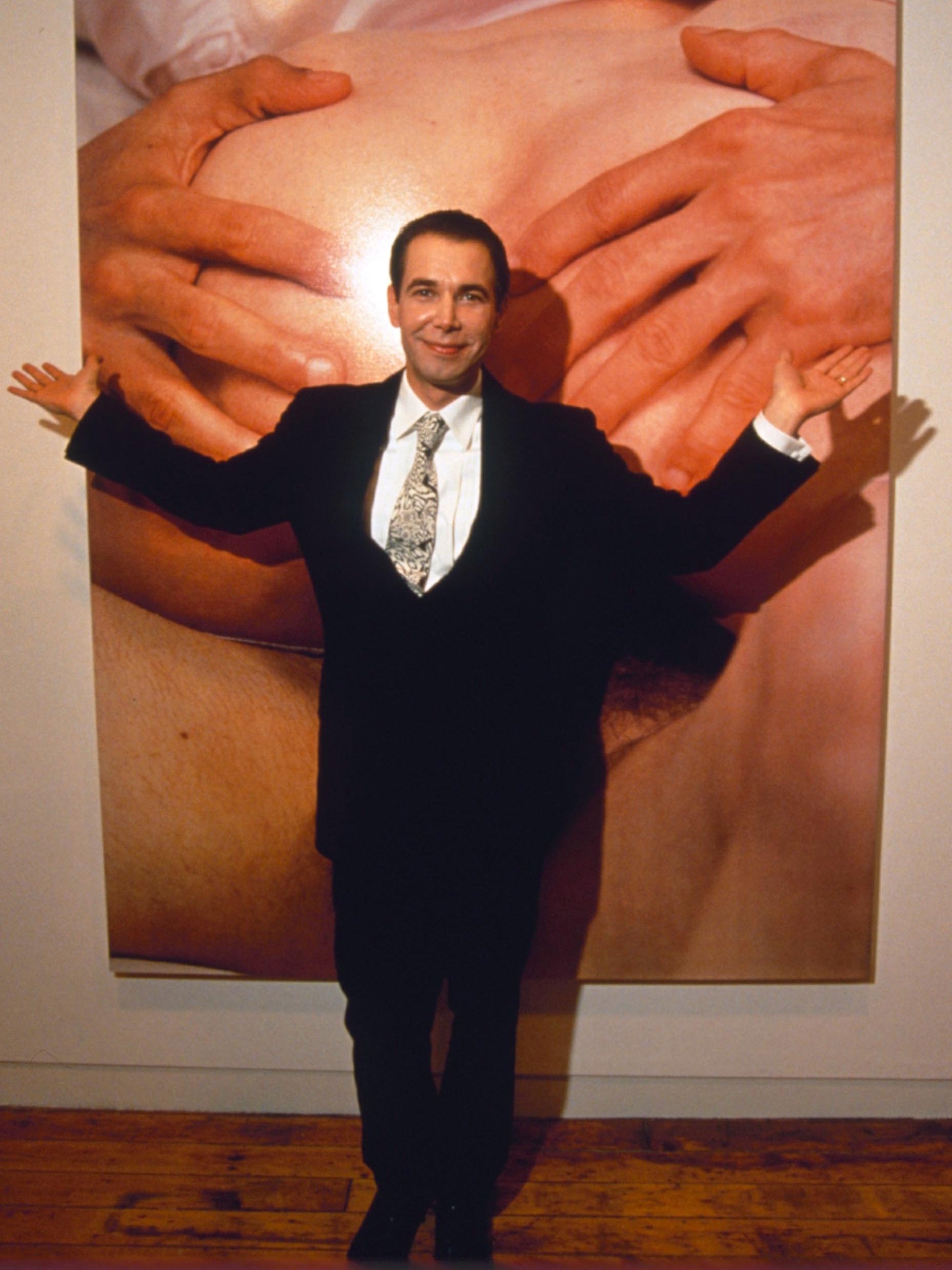

Jeff Koons interview: 'Some people certainly think that my work is kitsch, but I never see it that way'

Extract from an interview conducted by Robert Storr with Jeff Koons at the artist’s duplex in New York in early June 1990. First published in Art Press (October 1990) in French translation only, it appears for the first time in English in the anthology 'Robert Storr, Interviews on Art' (Heni, 2017)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Robert Storr: As we’re sitting under a painting by Ed Paschke, who taught both of us in the mid-1970s, why don’t we start there – looking back to the past and the time when you trained as an artist.

Jeff Koons: It makes my head spin just trying to remember. Let’s see... I went straight from high school to the Maryland Institute College of Art, where I took courses for three years with Albert Sangiamo, who helped me with my practice by teaching me what discipline really means. He’d make you work forty to sixty hours a week on the same drawing. And I always liked being forced to see things through to the end. But they didn’t really have professional draughtsmen there in Maryland. There were artists who in theory came from New York, from a professional context, but no one who was really a top-notch draughtsman.

In my final year, before my degree, I moved to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and that was where I met Ed Paschke. In Ed, I found someone who was making a genuine effort and trying to participate. Ed really let me into his inner life, and he showed me where he drew his material and his inspiration from. He also gave me a frame of reference, a basic strategy: how to avoid being self-destructive, how to put yourself in a situation that allows your work to really develop and to obtain political support. That doesn’t mean that you become some kind of sycophant or anything like that – simply that you don’t do anything that could damage you, which was very important for me.

. . .

RS: Do you see yourself as part of the Chicago funk?

JK: That’s what drew me there and I still appreciate the movement. Ed made phenomenal work, and I like what Jim Nutt and Karl Wirsum do. I do feel close to it, but it was too subjective for me. Little by little, I got the feeling that what I had dreamed the night before, or what I found interesting or exciting in visual terms, didn’t mean anything at all within my frame of thinking. It was too subjective. And then I stopped painting; I saw it as a kind of masturbation. I wanted to be done with painting.

By moving to New York, I could free myself, and even make a clean sweep of my past as a painter. I could start over again. I felt that I was getting rid of my sexuality, that I was detaching myself from it. But it was still a lingering presence, so I kept on cleaning things up. The ensemble I titled “The New”, with the vacuum cleaners arranged in vitrines is definitely the most desexualized work I’ve ever made. And then again, I think that the vacuum cleaners, enclosed in such a way, have a feminine sexuality, whereas a kind of masculine sexuality is suddenly highlighted in the containers. But the interface between these two ensembles is remarkably devoid of sexuality.

RS: In other words, you associate the act of painting, as well as the Chicago surrealist movement, at the time when you were painting, with a contestable subjectivity?

JK: Painting represents a very subjective practice in my artistic evolution: it’s more about tackling things that touch me personally than about the sort of stuff you’d hope might have greater social significance.

. . .

RS: Did you grow up among certain elements that are somehow related to the objects or images you reproduce in your oeuvre?

JK: My father was an interior decorator and had a furniture store. The store was spread across several rooms. There was a fake living room and a fake dining room, and then the kitchen, the study, and so on. My father used to sell a lot of French rustic-style furniture, and colonial style too. So I grew up with the notion of esthetics, the sense that certain things are beautiful. And also, I suppose, with a certain anal element. You wanted your surroundings to be uncluttered, to let objects find their voice and speak.

RS: When you install them, with what kind of voice do the objects you’ve selected speak to you?

JK: Some people certainly think that my work is kitsch, but I never see it that way. What I’m saying to people, actually, is that they shouldn’t erase their past, that they should blend together everything they are and move forward... My work simply tells people not to reject any part of what they are, to take their history on board. Their richness comes from what they are; they can feel free to become.

. . .

RS: One of the political aspects of your work that is often addressed in interviews is the relationship between what you call the middle class, and what you refer to as the bourgeoisie, by which I assume you mean the prosperous bourgeoisie, the powerful bourgeoisie, the ambitious bourgeoisie. Do you think that you are positioned somewhere between these two groups, or do you identify clearly with one or the other? Did you feel like a prisoner of the class you were born into?

JK: No. It’s not easy to say, but as a child I always felt like I was a little prince. And funnily enough, Ilona (Cicciolina) always felt like she was a princess. My mother never worked, but she encouraged me enormously and helped me during my years at university. That kind of thing, very middle-class. My parents have always lived comfortably. I grew up in a very large house, a Georgian-style mansion. We had horses, we had dogs. My parents were very, very 1960s, I think. They were members of a sports club. There was always an adventurous twist to their lifestyle. They didn’t accumulate money, they didn’t hoard. They tried to live their lives to the full at their social level.

As a result of that, I’ve always had a sense of floating within a class structure. I’m all the more disorientated as now I also belong to several cultures, to three cultures in fact. I spend part of my time in Germany, part of my time in Italy and part of my time in New York. That makes it all even more confusing. I think that in a sense I feel more and more of an outsider, and I’m starting to realize that my lifestyle is a bit different from the average. For a long time I refused to admit that, but it has become blatantly clear, even though I have the same pressures and responsibilities as other people do.

RS: One of the factors that motivated the appearance of the bourgeoisie as you define it – the class that aspires to upward mobility – was anger. Anger at not being able to progress, and anger towards an established patrician class that took its power for granted. Does that anger resonate with you?

JK: I’m sure that my motivation, at some primordial level, stems from anger or something very similar. Not anger towards an individual or a group, but the desire to keep moving forward. Perhaps I take the edge off it by putting this progress in the category of becoming. It is linked to the quality of life that I demand, which I want to be the best possible. I’m not thinking in economic terms: I’m talking about an intellectual,spiritual, biological quality of life. The economic side is just the icing on the cake.

When I decided to become an artist, I didn’t particularly enjoy just scraping by, living with very little money, and having to do a job that wasn’t the one I wanted to be doing, and spending my time doing something that wasn’t what I wished to be doing. That never appeared gratifying to me and I think I felt a certain kind of anger, not a deep-rooted anger, more a sense of tedium because life didn’t really fulfil me. In any event, what motivates me isn’t anger or revenge, but wanting to participate and make my life as beautiful and wonderful as possible. I don’t want a bigger slice of the pie than everyone else, but I want to be able to see that pie.

. . .

RS: And you are very controversial.

JK: Yes, but it is not intrinsic to my work. It is a reaction to it. My work never has that aim, it never puts itself in a position to produce that reaction, for the good reason that it has no political alliances. If it were to align itself politically on something, that dimension would become essential to it and its future would, of course, be very uncertain. But a future is the only thing that my work has.

RS: So, in moving from one group of works to another, you want to explore the limits of each successive practice?

JK: The important thing is to free myself. It is about being able to separate myself from Jeff Koons at this precise moment and from the limitations of this moment,and trying to broaden my horizon. After that, I get bored. Once I’ve tackled something and tried to push this exploration to its limits, throwing myself into it 100 percent,giving absolutely everything I have, why would I repeat myself? That’s one of the reasons that led me to make multiples. If I have to repeat myself, I want to do it precisely when my work provides me with the requisite material to define a program and participate in the cultural scene. It’s not like making a unique piece that people should make a pilgrimage to see. How many people would have a chance to see it? Whereas, this way, there are enough objects to see that it produces an effect. After that, I can move on to something else. Many artists fool themselves, believing that they create unique pieces, whereas their entire career ends up being nothing but one big multiple.

. . .

RS: You once said that if there were someone else you wanted to be, it would be Michael Jackson. He has remade everything, not just his physical appearance but also the world around him, creating his own personal Eden. Is that what you were thinking of?

JK: I respect Michael. He’s extreme. Michael has a lot of things to say, and he isn’t afraid of anything or anyone. I see a symbol of this intrepid nature in the radical transformations he’s carried out on himself – and he has to live with himself after those transformations. He can’t look in the mirror and know how he’ll look when he’s thirty-five. It’s terrifying. I respect his Thriller, but there was nothing especially remarkable about that record as a product. The art wasn’t his record; it was him. He was the real thriller, the man who knows no fear.

RS: Do you think that a perfectly constructed persona runs the risk of becoming grotesque or monstrous?

JK: I don’t know if I am really worried about that. I am aware of my persona as an instrument for communication but it’s not my only concern nor my sole mode of expression. I try to make objects that can communicate, I try to use my intelligence to work within this frame and find a system to respond to people’s needs. The persona of Jeff Koons is part of the ensemble, but the finished product is not just Jeff Koons. My private life, the life of Jeff, interests me much more than the life of Jeff Koons as it is perceived. Jeff’s life comes first, then comes the life of Jeff Koons the artist.

RS: And what about Warhol in all of that? Is it him you have in mind?

JK: There are a lot of other people who think about Andy and the links between us more than I do myself. OK, we’re a product of Duchampian history. [Marcel] Duchamp is the person who worked hardest to put art into the realm of the objective and I’ve never stopped wanting to follow him down that route. Andy used sexuality to communicate intellectual ideas. Many of Andy’s ideas speak to the genitals before they speak to the mind. That’s also how I try to communicate. I’m sorry to say this, because I love Andy’s work, but I’ve never felt the kind of respect for Warhol that Duchamp inspired in me. I respect Warhol more than plenty of other artists, but I think that people should look further back and link my work into what Duchamp was doing¸ instead of stopping at Andy. Is my new work Jeff and Ilona (Made in Heaven) [1990] the equivalent of the bicycle wheel? Is it the apogee of objective art since the bicycle wheel? I’d say that it is. I think that it’s more objective than the packet of Brillo.

Robert Storr’s ’Interviews on Art’ is published by Heni, £35

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments