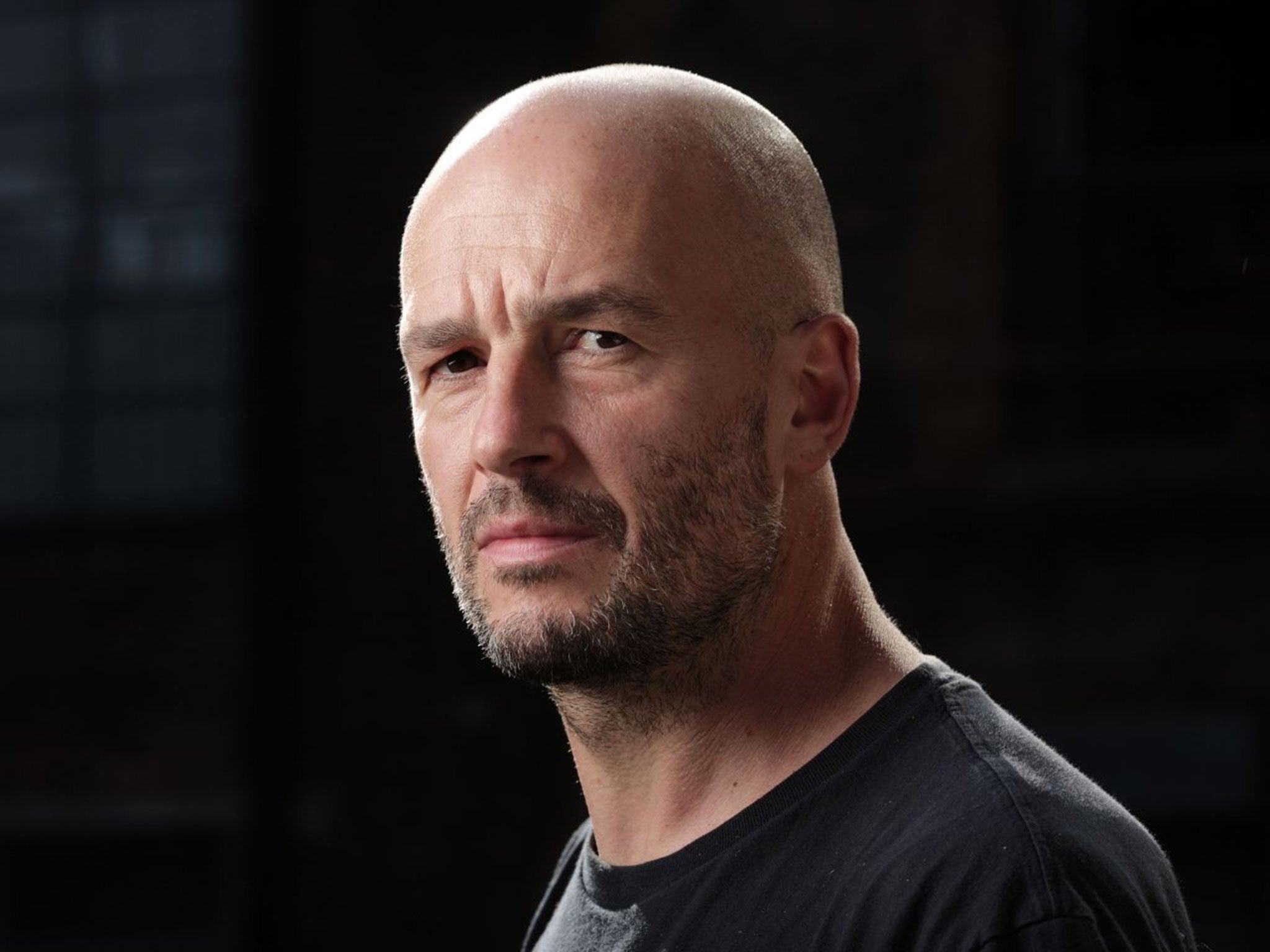

Jake Chapman: 'I'd draw the line at a Hitler's dog tattoo'

One half of art's bad-boy brother duo is famously disdainful of middle-class 'good taste,' but even he has his limits

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Talk about vintage Jake Chapman. Minutes into mulling the merits of crowdfunding an art exhibition – his and Dinos's, at Hasting's Jerwood Gallery – and he's segued into a discourse about hating "art as entertainment" and, worse, "homogenised culture", worrying about herd mentality. Jake, 47 and for ever half of the art world's notorious Chapman brothers, does not do uniform.

This gives a delicious irony to the ultimate reward possible for contributing towards the Art Fund's £25,000 target to help Jerwood pay for the October show – the chance to get a Chapman tattoo. The twist is that tattoos themselves, as the new chattering-class rebel identity stamp, have become "homogenised". And any inking that Jake does in Hastings will only exacerbate the situation. Or will it?

He grins, and he's off again, knocking the "arrogant notion that aesthetics and beauty are some kind of medallion of beauty of the middle classes". The Chapmans, whatever it might look like on paper, don't do middle class. "It's not going to happen that people get really cute little drawings." Pointing to a shaky, self-drawn line illustration of a skull on his left arm, done under the influence, natch, he adds: "Given that I'm covered in atrocious things on my arm, they're not going to get anything better than that."

All those tempted – Jerwood's director, Liz Gilmore, says interest is already "overwhelming" – might heed what happened when a Canadian gallery offered visitors the chance for some Chapman body art, this time professionally inked, at the opening of the brothers' latest Come and See exhibition. "They selected a bunch of drawings from our etchings. I asked after which was the most popular. A picture of an Alsatian dog [with] blacked-out eyes, which was a copy of Hitler's portrait of his own dog and all we'd done was blacked out the eyes. So it was essentially Hitler's dog. So people were getting Hitler's dog on their arm without knowing. If someone told me I had Hitler's dog on my arm, I'd probably chop my arm off."

Who knew? Art's bad boy – think penis snouts on child mannequins, defaced Goya prints, reworked Hitler watercolours and all those zillions of distorted toy soldiers in Hell – has his limits. Lest I think that age mellows, not to mention read too much into his family's recent move to the countryside (the father of three recently swapped Shoreditch for the Cotswolds no less), he puts me straight with a diatribe – his forte – about the need to "defend art from popularity and popularity from art".

His main qualm about getting Joe Public to help to meet gallery costs – with 28 days to go, the novel Art Fund initiative is 66 per cent in place – is "it can be manipulated". "You can engineer what kind of exhibitions you want by only crowdfunding certain things," he says. "A free market enterprise consensus means that actually your decision for certain exhibitions rather than others becomes financial." His fingers drum the kitchen table in his Hackney studio. "And I think maybe there should be exhibitions where only one person wants to go and that's OK. Rather than having this homogenised" – that H word again – "curation. Sometimes popular decisions are not always the right decisions."

Twenty years on, the Chapmans might exemplify the Young British Artists explosion that put art on a path to celebrity, riches and mass appeal, but that doesn't make Jake happy about conveyor belts of people lining up for the latest shows. "The one problem with the mass subscription to contemporary art is not the question of whether you would want to reserve it for some elite, but you want to reserve its complexity. The problem is, complexity and popularity aren't necessarily very good bedfellows. It's an odd turn of fate that, suddenly, cutting-edge radical, discursive, critical art becomes the beacon of gentrification." He loathes the notion that for the hordes "blown" off the South Bank and into the Tate Modern, "works of art become synonymous with taste rather than meaning". All told, the grin this time spreads to his eyes, he reckons it "makes us make our work even more tasteless to avoid the possibility that it can be appropriated to that gentrified sensibility".

As for the newish country abode, with its heated outdoor swimming pool and studio in the garden, well, it just helps to wind him up, the very thought of what he's become stimulating those anarchic creative juices. "The funny thing about living in the country is you really get to see your enemy. I drive from my house, past Ukip and Tory placards, listening to Radio 4, and by the time I get to London I'm furious."

This is handy given that Jerwood is promising the Chapmans' "biggest and baddest" show yet. Do they really still need to be bad? He assures me there's no "knee jerking" going on. "We're really very super serious about our work, and [it] really is torturously academic in terms of its intensity, its labour, its manufacture, its conceptualisation. So biggest, baddest doesn't really bring into focus the actual seriousness of the work. It has humour involved in it, but the humour is parasitical, and done with sincere hatred." He exhales, laughing, but seriously.

Given I must epitomise his loathed "mass subscriber", I'm increasingly happy that he's still even talking to me: after expelling a journalist from his studio in 2006, Jake told her newspaper it was entitled to "grace your readers with the meek tones of plum-mouthed Middle Englanders, but don't send them round to my studio. I'll make fucking mincemeat out of them, ha ha ha". He is typically blunt about what happened. "If I think someone's stupid, I don't really spend time talking to them."

In fact, he is blunt about everything, with an oddly compelling clarity of self-belief that makes me itch to read his school reports. His childhood is on my mind because the pair, plus their elder sister Gaby, grew up in Hastings, making the Jerwood show something of a homecoming. Not that Jake will talk about his formative years, detesting any attempt to ascribe a "regressive, confessional thread" to his work. He does admit Hastings – today "a great example of latter-day gentrification" – was a "harsh place to grow up". (His mother, whose parents were Greek-Cypriot, was a cleaner in the seaside hotels, and his father made fibreglass moulds for things like kids' slides.) He also says he "drew loads and loads and loads".

He is clear. Art is something artists do. "It's that simple. It's about intentionality," he says, nailing something that still provokes intense debate, especially when Martin Creed can win the Turner Prize for a light bulb going on and off in an empty room. And if they, as artists, say that reworking an old Goya print, or a Brueghel painting, improves the original, well, good luck disagreeing – especially when their new versions sell for so much more. Their next targets for a spot of "rectifying" will be artworks sourced from the junk shops of Hastings, or brought in by gallery goers when the show opens.

Fittingly, I leave Jake "rectifying" one of the brothers' own original works – an anatomically beautiful picture of two pigs mating etched into a copper plate. He scratches a cartoonish, otherworldly-looking guy into the new layer of wax that covers the pigs; this will be one of the limited-edition prints being dangled as a £450 reward for donating to their show. He pauses to check the spelling of Jerwood, before pressing down for the "M" of museum. Realising he's made a big mistake, he smiles dryly, adding "U", "S", "E" and "U" before scratching it all out and writing "Gallery" underneath.

Why should he care? He's Jake Chapman and, plus, if he thinks it's funny, it's funny. OK?

Curriculum vitae

1966 Born in Cheltenham as Iakovos Chapman; moves to Hastings when still a child.

1985 Studies at the North East London Polytechnic.

1988 Enrols at the Royal College of Art with his brother, Dinos, while also working as an assistant to the artists Gilbert and George.

1991 Begins his own collaboration with his brother.

1997 Great Deeds Against the Dead, Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic and many other of their collaborative works are shown at the Sensation Exhibition.

2000 Creates the sculpture Hell, consisting of miniature Nazi figures arranged in nine glass cases laid out in the shape of a swastika.

2003 Has a pot of red paint thrown over him by Aaron Barschak, a "comedy terrorist", in protest against his Insult to Injury series of works. Publishes his first book, Meatphysics.

2004 Marries fashion model Rosemary Ferguson at a ceremony at Christ Church, Spitalfields.

2007 Is criticised for saying that James Bulger's murderers performed "a good social service" which went on to cause a public media brawl with the journalist Carole Cadwalladr.

2013 Takes part in Art Wars at the Saatchi Gallery curated by Ben Moore with his brother.

2014 The brothers express their desire to open a tattoo parlour where they grew up in Hastings.

Jayna Rana