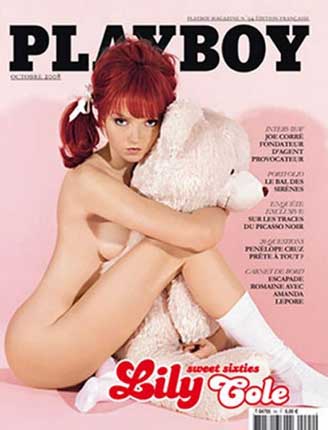

Is Lily Cole's appearance in 'Playboy' really art?

Lily Cole has said her appearance on the cover of 'Playboy' is art, but is it actually just a pornographic image of a young woman?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.YES Robin Simon

But is it art? That’s the question they asked about Édouard Manet’s Olympia when it went on view at the Paris Salon of 1865. The painting scandalised Paris. Not because Olympia was nude. But because she was naked. It’s the same difference with Lily Cole.

An artistic “nude”, so tradition has it, wears no clothes save, occasionally, for a wisp of drapery that falls, ever so artfully, and ever so obviously, across the pudenda. The naked woman, in contrast, such as Olympia or Lily Cole, wears a choker around the neck or a pair of socks.

Indeed, there is something startling about items of clothing clinging to the feet of the otherwise bare human form that stresses the naked over the merely nude. Olympia, for instance, has a shoe – emphatically not a slipper, but a shoe with a high heel – dangling from her left foot. The other lies beside her. The artist is telling us that she has taken off her clothes. In Olympia’s case, she is probably waiting for a client who has just sent some flowers in advance. She is certainly vulnerable, probably available. And, as a matter of fact, everyone knew that Olympia was one model in particular, Victorine Meurent.

If Manet’s Olympia is not art, I don’t know what is, even though it plays so daringly and successfully with expectations of what art might or ought to be. And I have not even mentioned the presence, at the foot of the bed, of the black cat, with its phallus-like erect tail. Olympia – Victorine – is, of course, posed upon a bed. And that is precisely how, suggestively, most artistic “nudes” usually appear. Manet was calling to mind earlier paintings of Venus, specifically Titian’s Venus of Urbino (Uffizi, Florence) and Venus, lest we forget, was the goddess of Love.

A bloke on a bed may or may not be your thing, but Lucian Freud is perfectly aware of the same intimations of nakedness over nudity and will show a man upon a bed wearing nothing but a black sock dangling off his toes. It is about drawing our attention, shockingly, abruptly, to the physicality and sexuality of a real person as opposed to, say, merely a personification of such an abstraction as love.

None of these intimations of sexual availability may be true of 20-year-old Lily, but the photographer is evidently, and consciously, working within the same tradition. And the images are still manipulating the same messages. It is there in the socks and, indeed, the teddy bear: not for nothing did Elvis Presley plead, “Let me be your teddy bear”.

The main point is that there are no “artistic” nude works of art of the past that do not have a sexually suggestive and arousing element to them.

That great country house, Knole, has a marvellous life-size sculpture of the ballet-dancer Giovanna Baccelli, mistress of the 3rd Duke of Dorset, at the foot of the stairs. She is lying on her stomach, bottom-up. The joke is that this very heterosexual woman is adopting the pose of one of the most famous and most collected statues of Antiquity, the Hermaphrodite. But the Duke also presented his closest male friends with small-scale models of this masterpiece by the sculptor Locatelli, so that they, too, could fondle his mistress. The fact is that if nude images are not arousing, whatever the prudishness surrounding them, then they are not very good works of art. Goya, remember, painted two versions of his Maya: one clothed, one unclothed. They were fitted upon a revolving system so that her male lover could see her naked – nude – and his official visitors with her clothes on. Both paintings are great works of art. And these snaps of Lily Cole look pretty good to me.

Robin Simon is editor of The British Art Journal

NO James Fox

Let's begin by dispelling the obviously puritanical arguments about Cole's most recent visual blitzkrieg on the European public. This isn't about whether one approves or disapproves of pornography; nor is it about whether one approves or disapproves of Miss Cole. And let us not even enter the perilous terrain of debating the propriety of having a naked model in Playboy embrace a teddy bear like a stroppy prepubescent. There aren't enough scandalised exclamation marks for that.

This is, quite simply, a matter of classification. Cole defends her latest endeavour by effectively describing it as art. "Nudity has always existed in art," she writes. "It doesn't necessarily 'debase' anymore than it celebrates ... the human body." She is no doubt correct. Nudity has always existed, and will always exist in art: the female nude is far and away the most persistent idea in humanity's visual imagination – from the Willendorf Venus of prehistory to Kate Moss's role as a muse to artists of today.

Cole is also right to argue that the display of the naked body can just as much celebrate as debase the body it displays. But it does not follow that Cole's naked body in Playboy is a nude.

The truth is she's just naked. A real nude is underpinned by a tiny but absolutely crucial distance from its audience. The nude is, and will always be, nude. She was never dressed, and will never be undressing. What's more, she will never be available to her viewers' sordid fantasies. Pornography however, is founded on the very dissolution of that distance.

It also doesn't follow that what Cole has just done is art. Art, of course, can be anything, but not anything can be art. Admittedly the last century has witnessed a fundamental overhaul of previously safe and closed categories. From where we are now, a bewildering range of objects, given the appropriate packaging, can be successfully categorised as artworks. Very few scholars would even contemplate refuting the fact that an upturned urinal (by Duchamp) is the most influential work of art of the past century.

The urinal is art not because it is beautiful – it is not; and not because it is beautifully made – it is not. It is art because its "packaging" made it art: because it was made by an artist, was exhibited in an art exhibition.

Cole's criteria are lying in shreds next to the clothes she discarded on the studio floor. If her performance is art, then what, for heaven's sake, is it doing in Playboy? Indeed, to argue that pornography is art is as nonsensical as arguing that apples, when not quite spherical, are actually pears. They are two qualitatively different products.

I wholeheartedly support Lily Cole's intention to use her naked body to celebrate and dignify the human form, and contribute to a rich and wonderful tradition in art. But Playboy might not be the place to achieve it.

James Fox is co-curator of the Statuephilia exhibition at the British Museum and consultant for 'The Story of Sculpture' on More4 tonight

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments