Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: How a married couple became Russia's most important living artists

Known for their large-scale installations and fictional personas, this first major UK show of work by the Kabakovs at Tate Modern will immerse you in their fantastical and escapist world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People not previously familiar with the work of the Russian artists the Kabakovs may well be in for a shock when they visit their large exhibition at the Tate Modern, the couple’s first major museum show in the UK. The Kabakovs, Russia’s most important living artists, are conceptual artists, seamlessly moving through various medium; painting, etching and installation incorporating a vast collection of different materials. Along the way we are asked to suspend our traditional way of looking at paintings, learn about the conflict of history and absorb what it was truly like to be an artist in a different society. Taking up a whole floor of Tate Modern, the Kabakovs immerse the viewer in the history of their past and also prospects of the future. Ironically, or luckily perhaps, they are not in the newly renamed Switch House, now the Blavatnik Building; a relabelling which, along with Blavatnik’s knighthood, attests to the fact that the main definition of services to the British nation and its institutions is now monetary.

Although they call themselves the Kabakovs, Ilya and his wife Emilia have distinctly separate roles in both their artistic practice and backgrounds – though they share the same Soviet Union birthplace, Dnepropetrovsk. Born in 1933, Ilya studied at the VA Surikov Art Academy in Moscow and began his career as a children’s book illustrator during the 1950s. He was part of a group of Conceptual artists in Moscow labelled non-conformists who worked outside the official Soviet art system. In 1985 he received his first solo show exhibition at Dina Vierny Gallery, Paris, and he moved to the West in 1987 taking up a six-month residency at Kunstverein Graz, Austria. Emilia Kabakov (née Lekach) was born in 1945. She attended the Music College in Irkutsk in addition to studying Spanish language and literature at the Moscow University. She emigrated to Israel in 1973, and moved to New York in 1975, where she worked as a curator and art dealer. Since 1989 Emilia has worked side by side with Ilya.

I first met the Kabakovs when I did a studio visit in the late 1990s. I was doing a profile for Modern Painters magazine and I drove from New York City to Mattituck, halfway out of Long Island onto the less fashionable fork. They had settled here when Ilya wanted more peace and quiet than the city could provide. Their house backs onto the water and it is in a large bright room where Ilya paints while Emilia is often in her large adjoining office, doing administration, sourcing materials and fundraising. They have now built a separate building to house their archive and models, and store Ilya’s often large paintings. They instal it as a quasi-exhibition for visiting curators and museum people. The house when I entered smelled strongly of chicken soup, a scent I associate with my childhood. Emilia had made us lunch and Ilya joined us, a quiet intense counterpoint to the more bubbly outgoing Emilia. The house was filled with work by Ilya but also by friends, many of them Russian.

Emilia is distantly related in some way to Ilya and said to me in an early interview she knew she was going to marry him when she was a teenager and their respective families would visit. Life intervened however, and it was not until 1992 that they became husband and wife, having worked together since 1989. The history is important as is the biography; Ilya started his career as a book illustrator for children and many of the early rooms in this exhibition reflect this graphic training. He also was on the outside of the official art practice, times were hard and this need to escape from the realities of their situation led to works of escapism and to the invention of various characters to project his thoughts upon. He created ten different albums, each named after a different character relating to different ideas, many of them based on his need for escapism from his often humdrum life. Each was illustrated with etchings and related to the story within. The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment is here graphically illustrated in a set of six paintings of collage and mixed media, with a gaping hole in the ceiling. Nearby is a disturbing installation, Box with Garbage, a work from 1984 and reimagined in 1994. Life is what you have, no matter how little, and anything can be precious is an oft repeated message.

Alongside the large installations, the exhibition will also contain the enchanting intricate working models that the Kabakovs construct for potential projects, including an idea for a vertical opera to be performed in the Guggenheim, imagined in 1998 and realised in 2008. Many of these ideas, including the wonderful Ship of Tolerance that will be shown in London later, contain an element of music that is partly due to Emilia’s training in music and education.

Escapism to space and flying is a constant theme; Ilya often set up works of little white men in windows in his Russian flat, trying to anticipate their escape, including the work, I Catch the Little White Men. The work from which the show’s title is taken, Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future, is a large wooden construction with paintings and a running text at the back. It relates to a recurrent dream Ilya had about running for a train and seeing it disappear into the distance with just the running text of its ultimate destination visible.

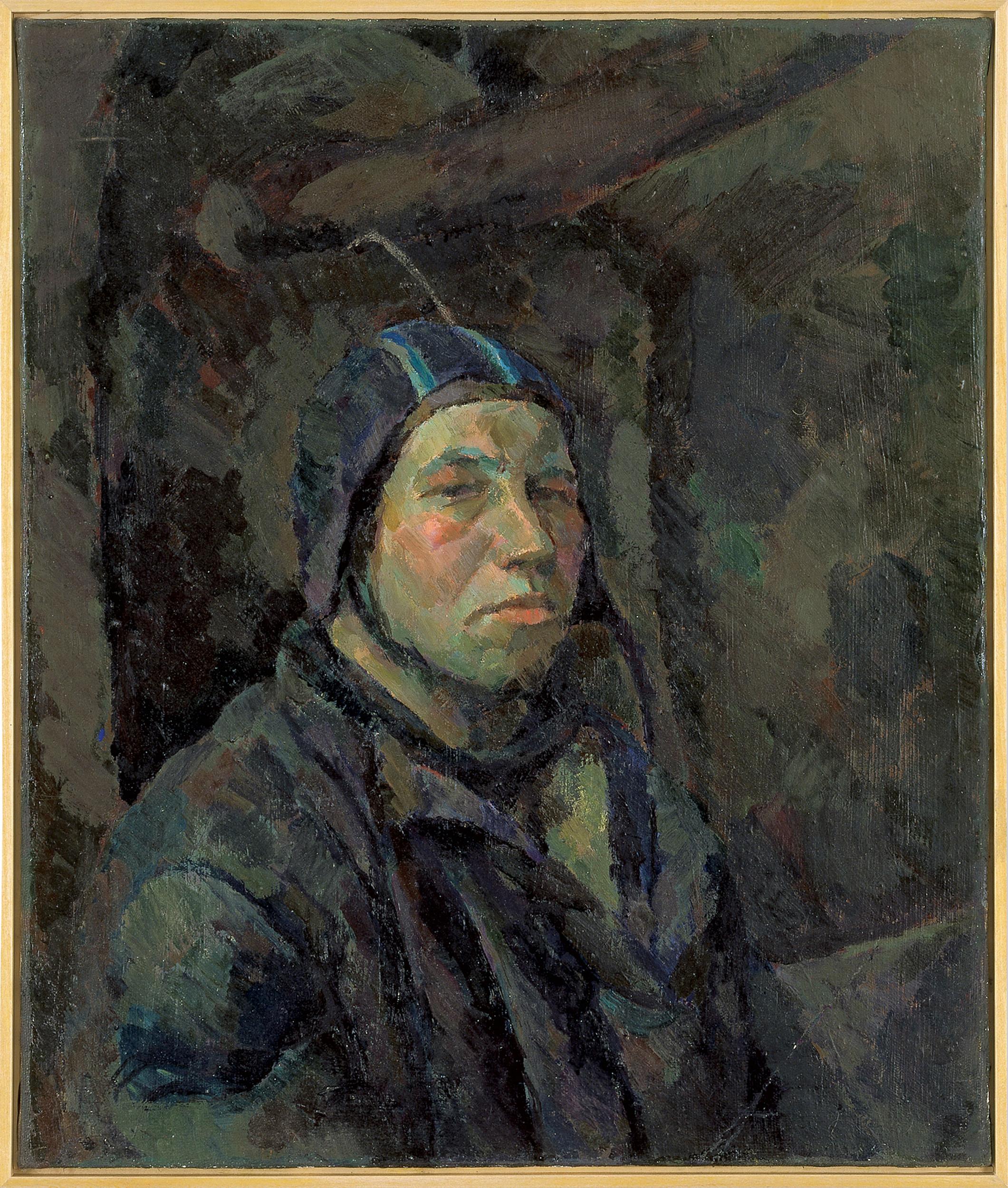

For viewers for whom installations of carefully installed garbage, pots and pans and discarded clothing are challenging, there are also a wide variety of paintings to titillate the eye. Kabakov has the ability to paint in many styles and in the past has invented several nom du paintbrush. Some of my personal favourite canvases are a group of paintings he did in the early 2000s under snow. With his fertile imagination he perceived the snow could act as a thick cover that could disguise cities and people. It was the antithesis of his flying escapes, burrowing down into the warmth of the enveloping snow. When I visited in that period he was painting in the large room overlooking the snow. I asked whether he was cold as he was wearing a coat and scarf; his fitting reply, “The paintings are making me cold.”

Ilya chronicled the tussle between the social realism, the official language of the Russian state painters, and the avant-garde school, integrating them often into one painting. Malevich meets farm workers – the past and present – distinct but bought together in a technique akin to speech bubbles or torn fragments.

When he was “reduced” to creating holiday paintings, Ilya enlivened the surface with bits of paper that on closer inspection reveal themselves as Russian sweet wrappers. The destinations might have been predictable but the paintings never become repetitive.

I went to the opening of the Garage in Moscow in 2008 as the sole press invitee. The Kabakovs had spent several months in Moscow prior to the grand opening, installing an old-fashioned museum within the spanking newly renovated former bus garage designed by the avant-garde architect Konstantin Melnikov as a bus depot in 1926.

The Kabakovs filled it with documentation and labels professing to be by three different painters, Charles Rosenthal, Ilya Kabakov and Ivan Spivak. The rooms – and there were many, the museum occupying a vast 8,500 square metre (two-acre) site, the size of a football field – had the traditional floors and strip lights of Russian museums. At the press view American curator Rob Storr refused to explain the concept of the “museum within the museum”, saying that nothing was as it seemed as all the paintings had indeed been done by one hand, albeit different, the documentation and labels were all fiction. He said when I asked why not explain it, “if the Russian critics did not realise this it was because they were lazy.” The concept seemed lost on the critics as well as the oligarchs pouring into the posh dinner, many with bodyguards, and glamorous younger women had high expectations of glamour not wishing memories of their past.

Perhaps this recounting of history explains why apparently the Kabakovs are not collected by many Russians. The explanation is because they now prefer to think of the future not the past, and how hard it was to live an artistic life within the Soviet Union.

How Can One Change Oneself, a pair of feathery wings attached to a leather harness, a work from 1998, sums up much of the Kabakovs’ work. It contains much of the pathos and ingenuity that is evident throughout this exhibition. With Kabakov’s exploration of angels ascending and also falling down, with its simple instructions and harness, the artist encourages the viewer to perhaps escape through the roof. In a world where increasingly the focus, even of institutions, seems to be about chasing money, I hope people will walk away from this show with their heads full of ideas, magic pathos and joy. They should do.

‘Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Not Everyone Will be Taken into the Future’, Tate Modern 18 October 2017-28 January 2018

www.tate.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments