How the Victorians brought famous artists back from the dead in seances

The work of spiritualist Georgiana Houghton is leading the art world's re-evaluation of 19th-century art and the dawn of the abstract

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

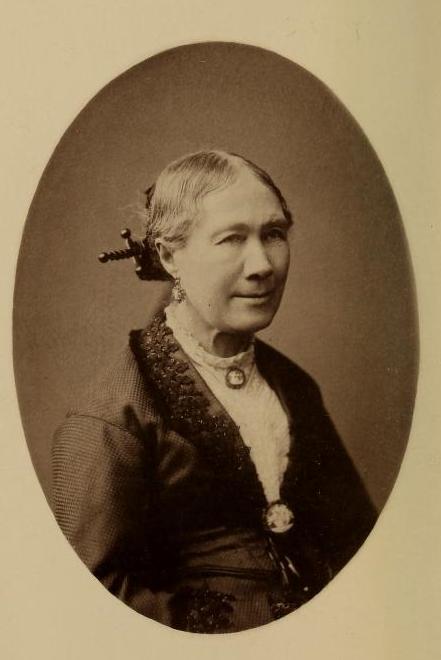

Your support makes all the difference.In the 19th century, in a dim gas-lit seance parlour, the spirits of Titian and Correggio returned to the mortal world to guide the hand of a medium artist, Georgiana Houghton. Claiming to be under the direction of her spirit guides, Houghton drew extraordinarily vibrant and colourful expressions of spiritual abstraction unlike anything seen before in art. As Houghton herself declared, her work was “without parallel in the world”.

Georgiana Houghton’s spirit drawings are pioneering examples of abstract art and a selection of these are now on display at the Courtauld Institute in London. The exhibition contributes to an emerging area of art historical re-evaluation of this period, which intends to change our understanding of 19th-century art.

A new spiritualism

Modern Spiritualism began as a movement in America in the 1840s, and its origin is often attributed to the Fox sisters of Hydesville. Spiritualists believed that the human spirit survives death and continues to take an active interest in the mortal world. Central to this movement were spirit mediums. A medium was someone who was perceived to have a special sensitivity to spirit communication, and through whom it was believed such communication across the two worlds was possible.

Spiritualism arrived in Britain in the early 1850s where it gained widespread popularity and caused a considerable cultural impact. This included a form of creative mediumship in which drawings and paintings were produced during seances.

Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) was one of many artistic British mediums. At the age of 45, she first became interested in spiritualism after the death of her younger sister and began attending seances. In 1861, she developed her skills as an artistic medium and throughout the 1860s and 1870s produced hundreds of symbolic artworks.

Only 40 of these now survive and a vibrant sample have been chosen for display at the Courtauld exhibition. In 1871, Houghton also chose to exhibit her work and she rented a gallery in Old Bond Street to present her spirit drawings to a London audience. This indicated that Houghton wanted her seance work to gain merit as art in itself, but she also used the exhibition to expose spiritualist ideas to the general public.

Among other British mediums who painted or drew in trance-states or during seances, reportedly under the influence of spirits, were Anna Mary Howitt, Barbara Honywood, Catherine Berry, David Duguid, Jane Stewart Smith, and William and Elizabeth Wilkinson. Importantly, these medium artists were significant contributors to a major 19th-century movement – Modern Spiritualism – which spanned across the globe from America to Australia, from Scotland to South Africa.

Their work ranged from abstract shapes to figurative forms, yet while their styles differed they were unified by the same goal, which was to use artistic mediumship to convince the viewer of the “truth”: that the spirit world existed and that spirits could interact with the living.

Life after death

Seance drawings and paintings were deemed to be spirit artefacts by fellow spiritualists. In order to understand both the visual language and the spiritual status of such artworks there was an emphasis on the way in which they were created. The medium would often go into a trance, during which it was believed that he or she would channel the spirit who would then author the artwork.

Experiencing the seance and watching the creation of spirit art was to allegedly witness the engagement of spirits with the mortal world, and was often deemed as evidence of life after death. Therefore, the artworks produced during seances were also thought to be evidence of spiritual interactions with mortals. These mediums’ works were intended to be understood by spiritualists who had sacred knowledge of the spirit world, and for those who did not have such an insight, the medium was necessary to further mediate the artwork’s meaning to the viewer.

An inscription on the back of one of Houghton’s drawings explicitly makes this point. On the reverse of The Eyes of the Lord (c.1866) her caption explains the concept of her symbolism: “The Trinity is represented throughout by my having always drawn three Eyes conjoined, but that will not be perceptible to those who have not seen the drawings in progress.”

Houghton was aware that viewers who attended seances gained an advantage in understanding the sacred message. The verso explanations on many of Houghton’s works and her daily attendance at the exhibition in 1871 were practical measures to help the viewer access the meaning of the drawings. It also ensured that the sacred knowledge of the spirit world was imparted to a wider audience, an audience whom Houghton hoped would become convinced of the teachings of spiritualism.

A forgotten art form

The collective work by medium artists is an overlooked area of 19th-century artistic output. It was forgotten by the mainstream mainly due to a lasting scepticism of the practices that produced the “spiritual” oeuvre. Fraudulence was often rife among mediums, and most of the British medium artists listed above attracted their share of suspicion and scandal.

The curators of the current exhibition draw attention to a 19th-century critic’s response to Houghton’s 1871 exhibition. From a position of distrust toward spiritualism, the critic stated: “We should not have called attention to this exhibition at all, did we not believe that it will disgust all sober people with the follies which it is intended to advance and promote.”

Subsequently, such sceptical views contributed to the rejection of spirit art as a subject unworthy of consideration. Instead, this genre of outsider art faded into obscurity. This was irrespective of its legacy on automatic drawings practised by French symbolists, Dadaists and Surrealists.

Despite this, there have been recent attempts to re-examine the importance of these spiritualist works as innovative and pioneering for their time. One approach is to introduce new audiences to this different type of art in gallery exhibitions, including both the current exhibition of Houghton’s drawings at the Courtauld Gallery and the recent exhibition on Hilma af Klimt: Painting the Unseen at the Serpentine Gallery, also in London.

Three decades after Houghton produced her spirit drawings, Hilma af Klint, a Swedish spiritualist and theosophist, produced large abstract paintings also allegedly under the influence of spiritual forces. These recent exhibitions in London have given new consideration to the colourful and abstract art forms of these medium artists, which precede Mondrian and Kandinsky.

A review of Houghton’s exhibition in 1871 pronounced it to be “the most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment”. If the 2016 exhibition at the Courtauld can convincingly redefine our assumptions of 19th-century art, which it is sure to do, that review is as relevant today as it was 145 years ago.

This article was first published in The Conversation. Michelle Foot is a Doctoral Researcher in History of Art, University of Aberdeen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments