How political is the new generation of Chinese artists?

Activist Ai Weiwei features in an explosive collection that showcases the major developments in Chinese art over the last 40 years, Inevitably, there is a political theme, says Karen Wright

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Whitworth gallery, part of the University of Manchester, recently named as the Art Fund's Museum of the Year 2015, is the last European venue to host the M+ Sigg Collection before it departs for the West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong. The collection will be installed in the M+ museum (due to open in 2019) with its own new Herzog and de Meuron-designed building.

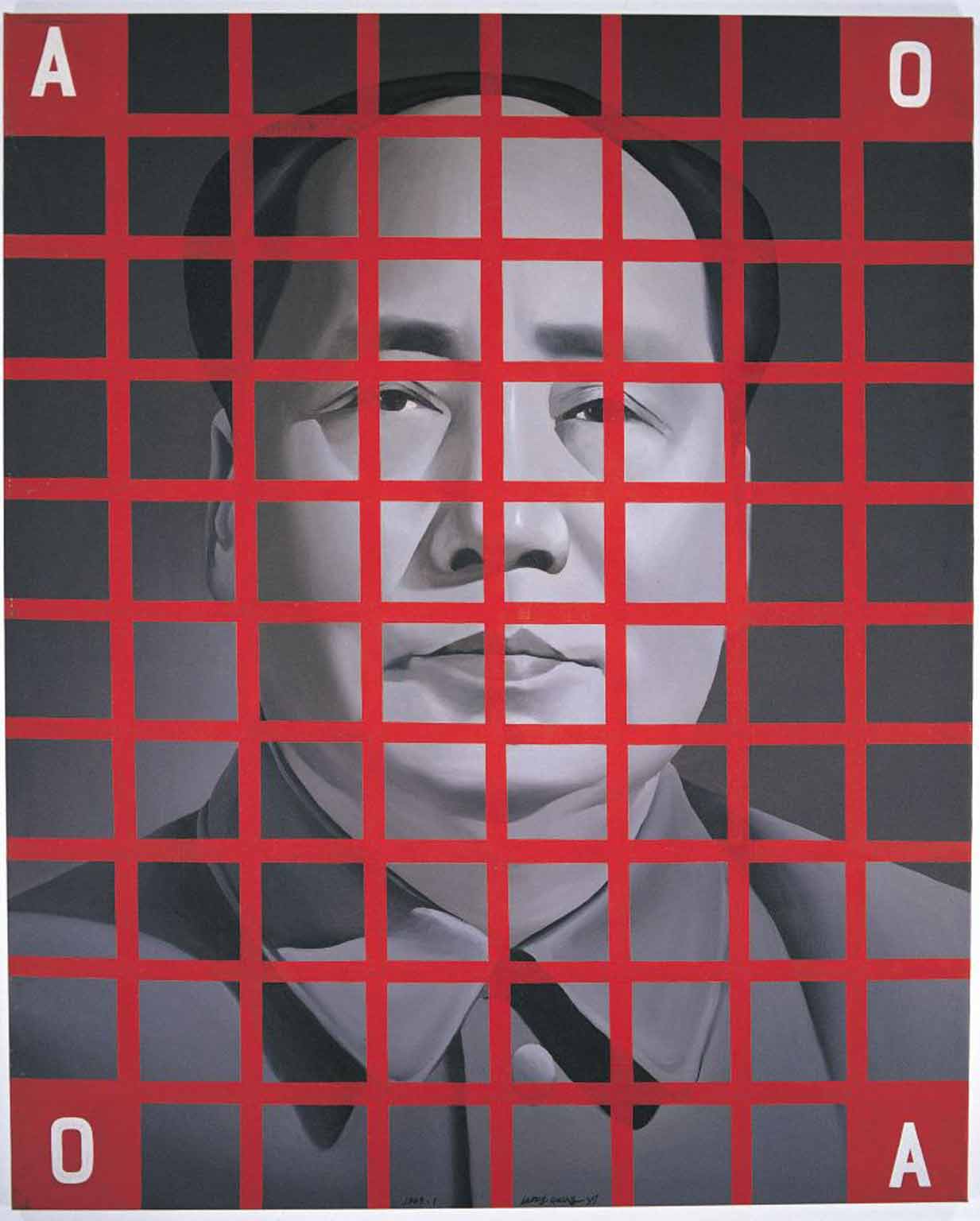

This is a totally engrossing and informative show, which engages even those like myself who, in the past, have found Chinese art to be impenetrable. It showcases the brief but explosive history of contemporary Chinese art over the last 40 years as artists dealt with a repressive regime, an outdated academy system and a new engagement with the West in the "Olympic years".

It also demonstrates that artists can raise the consciousness of the world and change the way we think. Images such as Liu Heung-Shing's Beijing – Rushing Students to Hospital (1989), the famous photograph chronicling the riots in Tiananmen Square, was flashed around the world and became the symbol of shame for China.

The work is drawn from the astounding collection of the Swiss collector Uli Sigg, who went to China in the late 1970s to set up the first joint venture company between China and the western world. He then became Swiss ambassador to China. Living there he was in a unique position to educate himself about the art, both through research and learning from the artists he sought out. The artist Ai Weiwei recalls: "I met this man who liked art so much; he was probably the only ambassador in China, in the past and in the future, who hung real quality pieces of art in the embassy, both western and Chinese."

In the first room hangs Untitled (Three Leaders), a painting by the then young artist Ai Weiwei. He was a member of the "Stars" group, the son of a dissident poet, brought up largely in a work camp with his parents. He moved to New York City in 1981 in self-imposed exile to study painting. This triptych is his reaction to the events in Tiananmen Square, implicating the leaders not the students. This is also one of the few remaining canvases of the period, as he threw out his work when he left the US in 1993 to return to China to see his sick father.

The middle room is dominated by Still Life (1995–2000) by Weiwei, an amazing collection of 3,600 stone-age axe heads, its dates reflecting the artist's ongoing obsession for collecting. Opposing the serenity of this work is the powerful Family Tree by Zhang Huan, a performative set of photographs where the artist used his own face as a canvas for traditional calligraphers to cover it with lyrics about his family. During the day, nine photographs were taken to record the various stages. By the end his mien was literally unrecognisable, the words illegible.

The final chapter of the story, after 2000, is perhaps the easiest for us westerners to understand. Here Chinese artists have been exposed to western techniques and images, and have drawn them into their own methodology of global practices. They have also been confident enough to revert to the traditional, while using their newly acquired western language.

One of the most striking moments in the show, and Sigg tells me one of his favourites, is the huge digital photographic work Looks like a Landscape by Liu Wei. The work is a huge assemblage of buttocks and body parts complete with hair and insects. From a distance the artist is seemingly referencing traditional Chinese landscape paintings, but it soon becomes apparent that he is turning the tradition upside down, and in doing so creating a powerful and disturbing image imbued with an unexpected eroticism and beauty. This is a political work in its truest sense using artistic language, referencing the past and the future.

There are several arresting videos, two of which show different uses of video/film-making at their highest levels. Yang Fudong is perhaps the best known Chinese film-maker. His Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest (Part III) (2005) uses a black and white calligraphic palate and traditional settings in odds with its totally modern storyline, which charts the problems of rapid urbanisation in China.

New Beijing, a striking painting by Wang Xingwei, takes as its subject Liu Heung Shing's photograph, replacing the injured students of the earlier image with wounded penguins, a surreal choice of animal as it is the only animal not given a mythological connection in China.

A few years ago I interviewed Uli Sigg with Ai Weiwei in Berlin. Sigg and I were talking happily about his love of collecting when I noticed that Weiwei had fallen asleep. I asked if we should wake him up and Weiwei said, "I am not asleep, I am just listening to the two of you talk", with a beatific smile. It was not long after that Weiwei was placed under house arrest. I remind Sigg of the occasion and ask him if he is still in touch. "Always!," he says. I ask Sigg why he has decided to give so much of his collection away – 1,500 of the 1,700 or so works. "I always meant the collection to be placed in a museum in China. I purchased it as a storyline of the history of its artists and its history."

This personal history of a huge country, carefully selected both by Sigg and Whitworth's curators, enlightens us painlessly to the turmoil of this amazing country.

The M+ Sigg Collection: Chinese Art from the 1970s to Now is at the Whitworth, Manchester (0161 275 7450) to 20 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments