How female artists are fighting back

'Female painters are at the forefront of exploring the possibility of the medium to an entirely new extent'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits show black women and men set in vague surroundings or against a dark backdrop. The muted tones and settings feel historical but the figures seem to belong nowhere. They might have striking features: a pair of immaculate white sneakers, faded blue jeans, a black women with bleached bright blonde hair, yet it’s not possible to locate a specific time or place.

Her subjects are fictional, people don’t sit for her, which makes it seem that these paintings are about no one in particular, and more about painting itself. She paints each portrait in a single day, in order to achieve her singular effect which she only finds before the paint dries.

Boakye’s exhibition at the Serpentine is one of a number of museum exhibitions this year dedicated to female painters who paint figures.

“I think female painters are really at the forefront of exploring the possibility of the medium to an entirely new extent,” says Daniel F Herrmann, curator at the Whitechapel gallery. “They’re using painting as a medium of subversion and resistance, which is interesting. Very different to the concerns of the 1980s which were dominated by large male figures swinging their brushes around.”

The mother of this generation is Marlene Dumas who, with her haunting and sensual images, contributed to the re-emergence of figurative painting in the 1990s. Her recent retrospective at Tate Modern filled rooms with ghostly images of men, women and children. Exploring subjects from politics to celebrity and pornography, it made for a powerful display.

“One looks for people to look up to, that’s partly why the Marlene Dumas show is so thrilling because it’s so incredibly good on every level. I think she’s the greatest living painter, whether she’s a man or a woman. Her show was breathtaking,” says artist Chantal Joffe – whose portraits of women were shown at the Jerwood Gallery earlier this year, and will be showing in the National Portrait Gallery, and Jewish Museum in New York City. Considered one of our most prominent portrait painters, Joffe was an early admirer of Dumas.

“I was aware of Marlene Dumas when I was at the Royal College of Art and I looked up to her, maybe she gave me a licence to do something,” she says. “I was very influenced by her. By that I mean that, even though I always painted figures, she gave me a freedom.’

Since the 1990s, an entire generation of female figurative painters has emerged – women who choose to tackle this difficult, history-laden medium. Younger than Dumas, there’s British artist Jenny Saville, who paints vast fleshy female figures, and fellow Brit Cecily Brown’s sensual figures hang on the edge of abstraction. Irish painter Genieve Figgis’s colourful and macabre work shows frilled Rococo women melting into their surroundings. In America, Elizabeth Petyon paints intense colour-filled portraits of celebrities.

Dana Schutz’s awkward and brutal compositions show uncomfortable situations such as a woman shaving her bikini line on the beach. Ellen Altfest’s recent exhibition at Milton Keynes gallery displayed her hyper-realist portraits of men, every chest hair outlined with unflinching detail. Lisa Yuskavage uses historical techniques in her saucy paintings of cartoon-like nudes set in atmospheric landscapes. New Yorker Inka Essenhigh paints visionary images of nature and human-like figures.

One of the difficulties female painters face, particularly figurative painters – compared to more recent mediums such as performance or conceptual art – is the weight of art history, dominated for centuries by men.

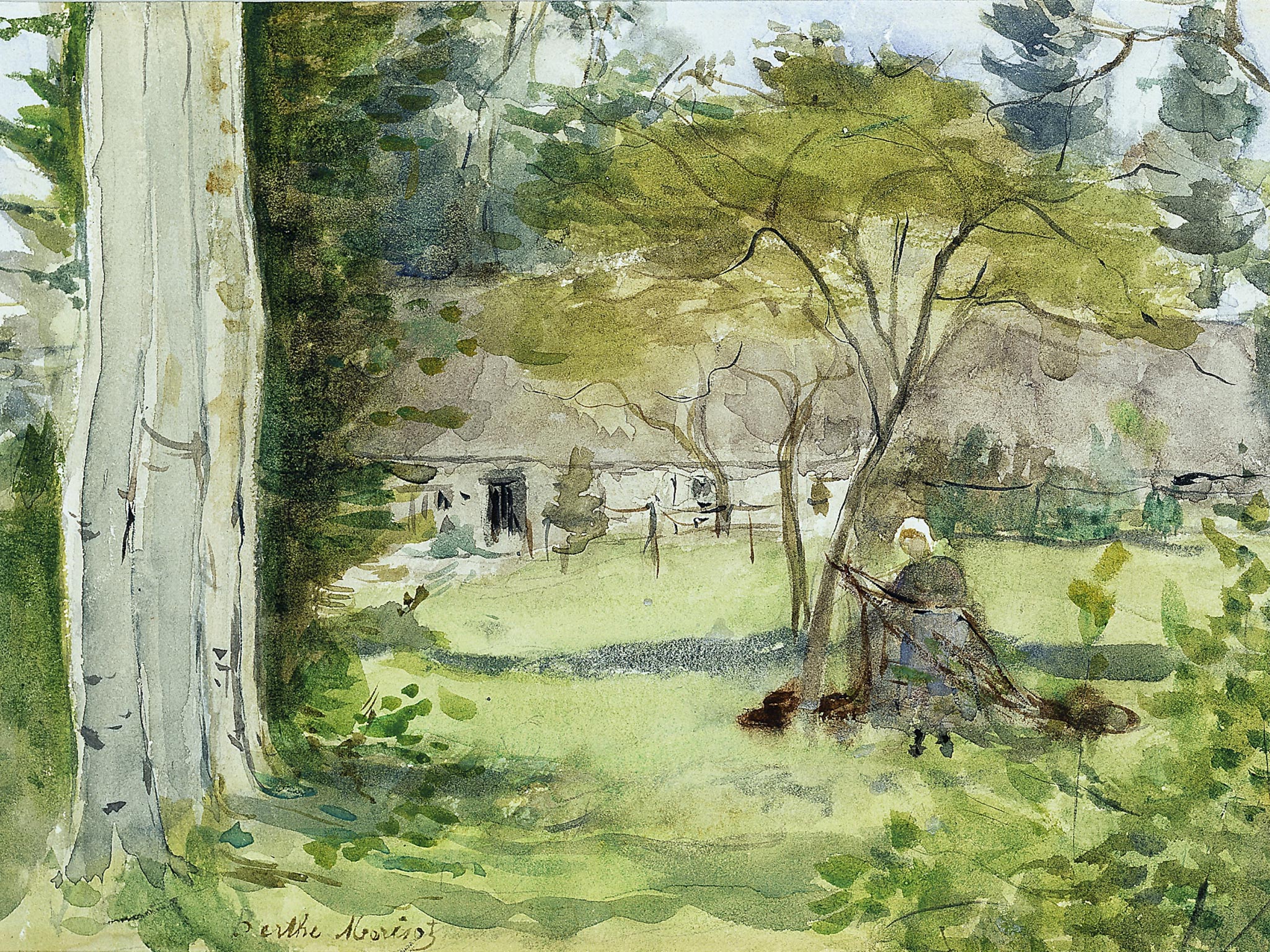

“There are a handful of female painters in art history,” says Joffe, “Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Gwen John, Georgia O’Keeffe, but not many. It does make you feel disenfranchised, because not having people to look back at is strange. They are some you have to dig them out, like Elisabeth Vijée Le Brun. Now we have a generation of female painters,’ says Joffe.

“I always wanted to be a painter,” says Inka Essenhigh. “At art school there was some talk about if could you make a living. Some people believed painting was a male thing. Women had to go and discover and claim an art that they did naturally.”

“There is a tendency even now to take male painters more seriously than female painters, in any context,” says Joffe. “If I say to someone, ‘I’m an artist’, they might go, ‘hmmm’, and presume that I’m a watercolour painter on Sundays. There’s just a prejudice, they don’t assume that I’m a serious artist.”

“I think women still have a difficult time as painters but it is certainly better than it was,” says Celia Paul, a painter of the same generation as Dumas. As a female portrait painter, she occupied an isolated position in the art world for many years. “I was very encouraged by the male tutors at the Slade and by the male artists that I knew when I was young. I felt supported and I wasn’t really aware of being looked down upon or considered lesser because I was female. That changed when I reached my thirties.”

Of course, it has never been that brilliant female painters didn’t exist, it’s just that they were blocked or hidden from public view. “The painter Alice Neel was written out of art history,” says Herrmann, “because art history was usually written by old white males. That is changing. We’re now in a position where we can look at the writing of art history from a more holistic point of view and not just the agenda of white males.”

Women painters still face challenges. Roughly 65 per cent of art students are women but only 35 per cent of artists represented by London galleries are female. A conservative art market favours men – Marlene Dumas is the most expensive living female painter but her record at auction is £3.2m for The Visitor, compared to £16.6m for a canoe painting by Peter Doig.

“There are strong obstacles for women,” says Frances Morris, Director of Collection, International Art, at Tate Modern. “The role models and infrastructure for women to come to the fore are not as present as they are for male painters.”

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Versus After Dusk is at Serpentine Gallery, London W2, to 13 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments