From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia, Dulwich Picture Gallery - review

Carr shed her stuffy Victorian upbringing and captured the beauty of the Canadian landscape while living among the country’s native people.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This is a risky show for the Dulwich Picture Gallery: its biggest budget for a single show to date and it is for Emily Carr, a female artist, almost unknown in the UK or indeed in Europe. Importing a troop of Haida dancers and a master carver chief to accompany and bless the opening was both a costly and memorable choice. Securing amazing loans of historic artefacts from various British museums took tenacity, while the loan of Carr’s fragile early drawings from Canadian museums gives an invaluable insight into her working methods. Sensitively installed in the difficult galleries, this is a beguiling show, and deserves to be one of the biggest blockbusters of the season.

Carr was born in Victoria, Canada, in 1871, the youngest of five daughters – her younger brother died tragically young. Her parents were British and proud to be Victorian in style; the house was a shrine to Britishness, and she was expected to behave decorously. She said: “I had English ways – English speech – from my English parents, though I was born and bred Canadian.” She preferred to think of herself as the “naughty one”, even though she did well enough at school. Both her parents died when Carr was in her teens and aged 18 she persuaded her guardians to send her to school in San Francisco, from where she returned a good, if uninspired, watercolourist.

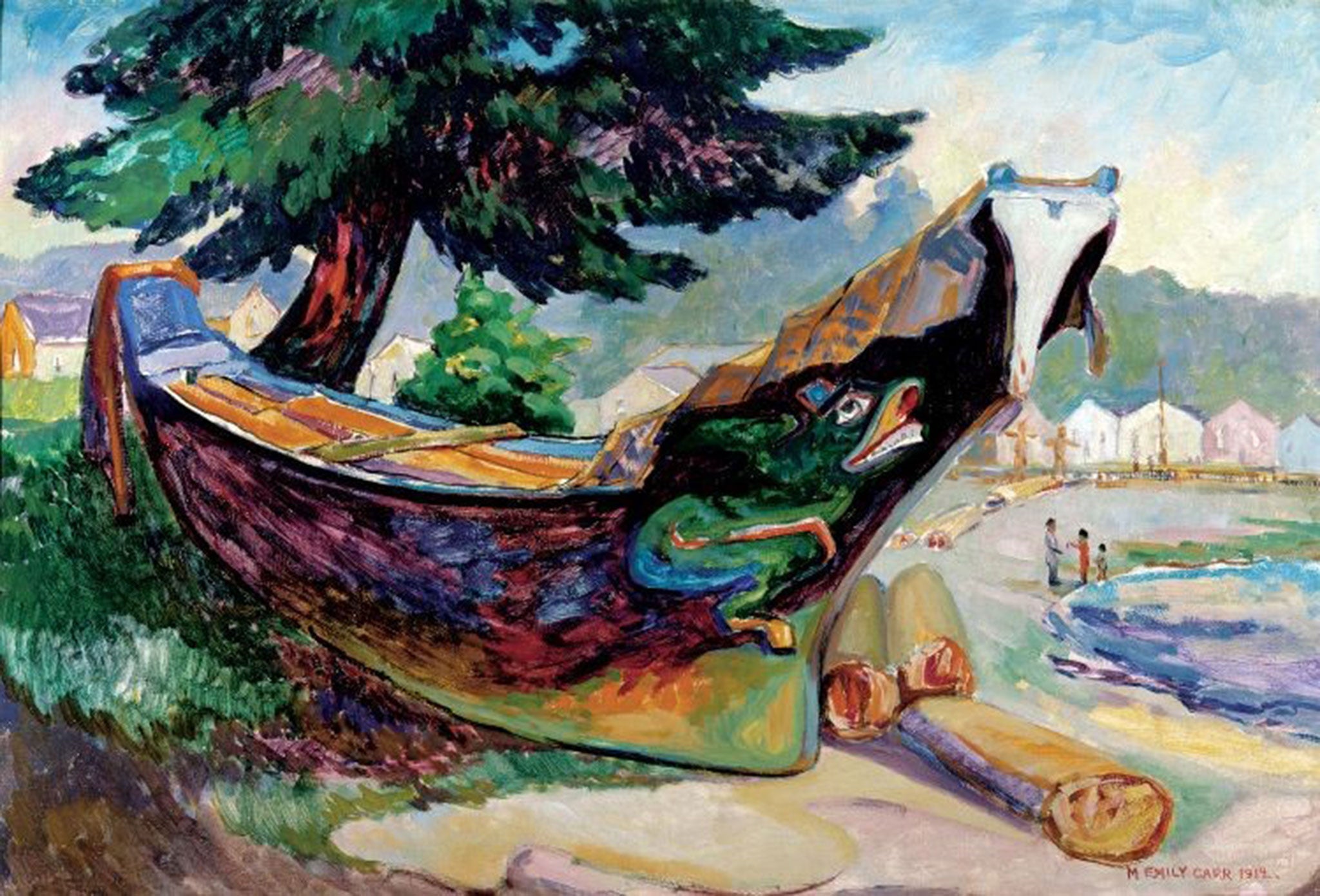

It was Carr’s determination to learn more that led to her guardian approving her trip abroad with her sister Alice as her chaperone. She came to England, studying first in London, which, like all big cities, did not suit Carr, so she decamped to St Ives in Cornwall. By 1904 she was back in Canada and made her first trip (along with Alice) up the coast to Sitka, Alaska, where she saw indigenous objects like totem poles. She kept a journal, which has only recently resurfaced, and more importantly she discovered her mission and place.

By 1910 she decided she still did not have the right artistic techniques to do justice to this work, and through an exhibition and auction in her studio raised money to return to Europe, this time to Paris (again with Alice in tow). She encountered French contemporary painting, and studied with the Scottish artist JD Fergusson; but Paris, like London, made her ill, and after a period of recovery in Sweden she returned to the northern coast of France, to Brittany, where she worked with the New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins, before returning to Victoria, arguably as the most progressively trained artist in Canada.

She travelled north, an ambitious trip along coastal northern British Columbia, and returned to hold a large exhibition in 1913 of her newly vibrant work. But it did not attract the buyers. Almost in despair, she offered to sell the work to the provincial government and it was declined. Depressed and destitute, she decided to raise money by building a lodging house, a scheme fraught with difficulties. She was notoriously irascible, preferring the company of any creature to humans. At one point, she was reduced to living in a tent in the garden and pushing a pram to the local park laden with animals – including her pet monkey Woo – returning with clay to make lumpy pots to sell to tourists (none of which, mercifully, are included in this exhibition).

This could have been the end of the story as Carr ceased painting during this period. But then Eric Brown, the English director of the National Gallery of Canada in Ontario, saw her work and asked her to send some in for a show, Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern, which he was holding in 1927. Travelling to Ottawa and Toronto she met the Group of Seven, Modernist landscape artists, including Lawren Harris, the group’s unofficial leader who had, like Carr, an overwhelming love for the landscape of Canada and saw in it the presence of the divine. She returned to the west coast restored in her belief, if not in robust health. She was 56 years old, and managed only one more extended trip into Alert Bay, the Queen Charlotte Islands and the Nass and Skeena rivers.

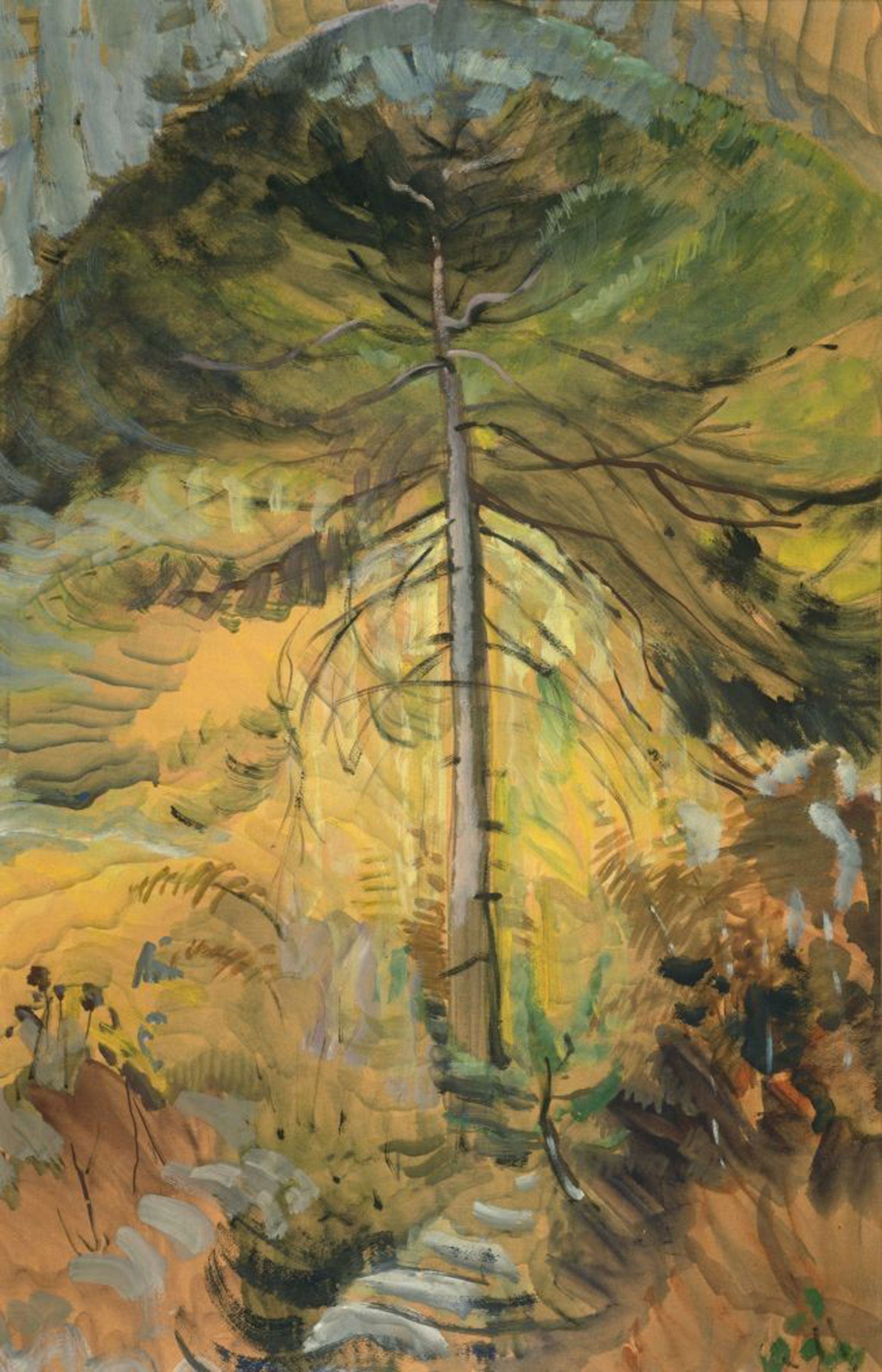

She kept up a continuing correspondence with Harris. In one letter he queried Carr: “The totem pole is a work of art in its own right and it is very difficult to use it in another form of art. But how about seeking an equivalent for it in the exotic landscape of the island and coast, making your own form and forms within the greater form?” This, along with the words of Walt Whitman, led to Carr adopting the tree and forest as the source of her artistic explorations. In 1930 she acquired the Elephant, a caravan that she could extend with tarpaulins; she could move it into the landscape and along with her furry companions could settle near the trees. Her constant drawing in charcoal resulted in extraordinary compositions like Untitled (1929-30) – formalised tree forms with totemic details – which shows a muscularity and mash-up of indigenous details and nature.

Happiness (1939), an aptly named painting, shows a singular central tree. The experience of being there is captured in both the name and in its seeming effortlessness. She invented a new technique, buying reams of cheap brown paper and using oils thinned with gasoline, allowing her to paint in a quicker, quasi-watercolour style. In Windswept Trees (1937-38) all is glimmering, swirling and twinkling, with nothing in stasis. Artist Peter Doig says of this painting, his personal favourite in the show, “You are seeing the trees but you are also hearing them.”

With her health continuing to fail, she reluctantly sold her caravan and turned to painting the sea and sky in Victoria, looking longingly at the mountains on the horizon; focusing as many artists do in their later works, on the sky. Visions of mortality fill the painfully beautiful Sky (1935-36). These works carry the spiralling marks of energy. While many compare her skies to those of Van Gogh, to me they carry more of the movement of the Futurist Umberto Boccioni.

Towards the end of her life (she died in 1945) she could no longer paint and turned to writing. In 1941 she published her first book. Klee Wyck was a series of humorous and poignant vignettes of travel, winning a literary medal and implanting her name firmly into the consciousness of Canadians, who embraced her rapturously. For them, she represents the intrepid pioneer woman who fearlessly travelled into the wilderness, lived among the native people, recorded their lives and, more to the point, portrayed the spirit of the land they inhabit.

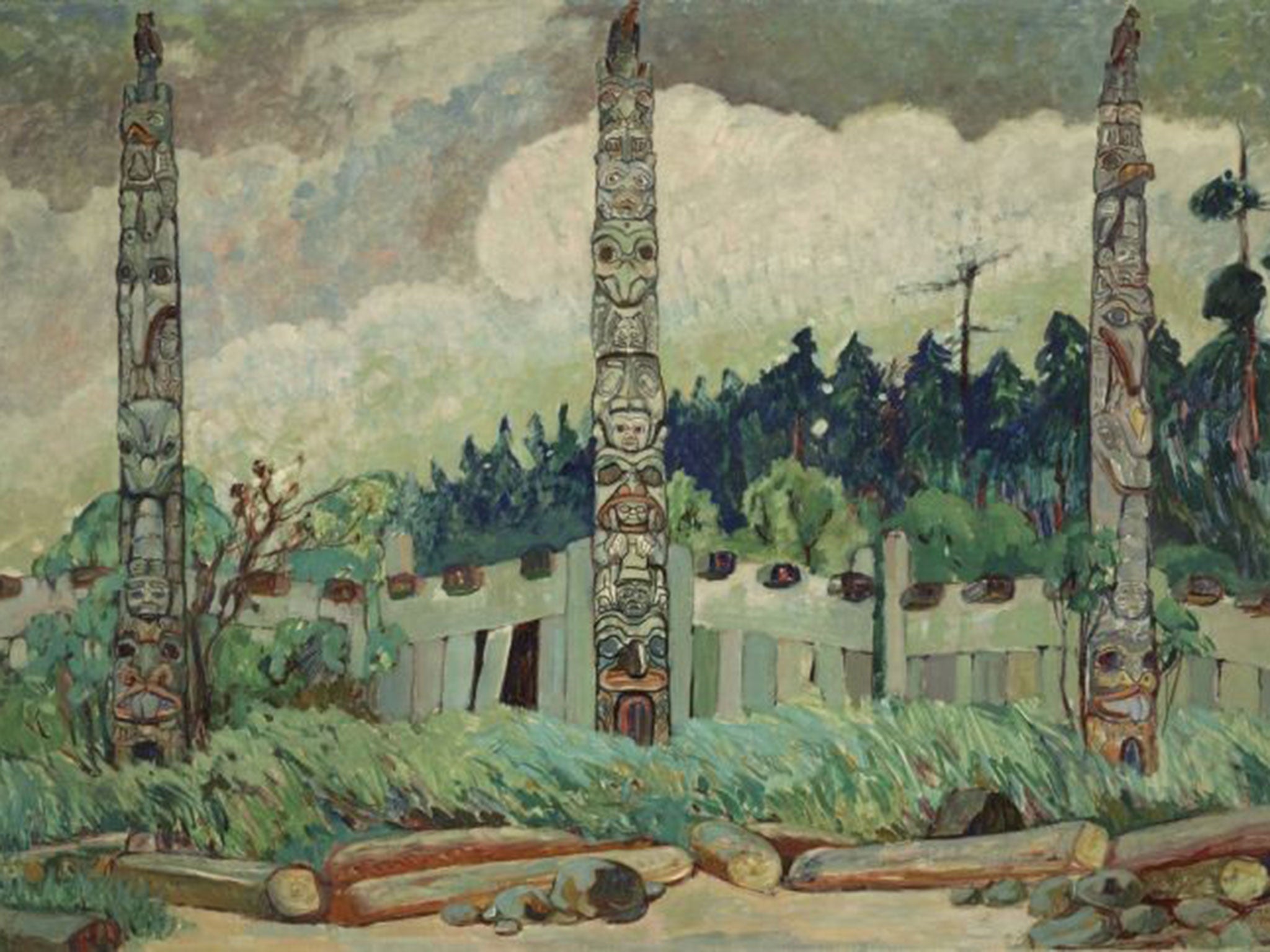

At the opening, I spoke to James Hart, the Haida chief whose members currently number a healthy 7,000. He is happy to be in London with his group of performers, “all artists”, saying that he sees this trip as a “study trip for our guys”. They are going to see all the museums, including the British Museum and the Pitt Rivers, that have loaned valuable artefacts to the exhibition. He is an artist, like the rest of the troop, and is currently engaged in planning a large totem pole, Reconciliation, to be placed in the University of British Columbia. “The cedar log is 60ft tall, they are building a road into the forest to get it out.” Carr’s powerful painting Totem and Forest (1931) shows his family totem pole, carved for his great great-great grandfather in the mid-1800s.

Indian Church (1929), one of Carr’s most famous paintings, shows a church dwarfed by the forest. Carr has compressed the scene, crowding the building into its forest setting, transporting the graves close to the flanks of the church. In reality the forest is further away; the church sitting in a large clearing and the cemetery at a polite distance. When I hear the story of her work being dismissed by local government, perhaps because of this artistic transposition, I recall asking David Hockney how he, an artist who works often en plein air, could completely rework his local village, Sledmere in Yorkshire. His terse answer was, “I am an artist. I am allowed to change things. It’s artistic liberty. I am depicting, but I am not a topographical painter.”

I love the integration of the First Nation people into Carr’s work, her respect of others and their heritage, the almost sculptural carved forms of both trees and indigenous art; but it is the room of mere trees that captivates me. Surrounded by thickets of trunks, the lightness and freshness of touch, I can almost feel the wind in my hair.

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21 (020 8693 5254) to 8 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments