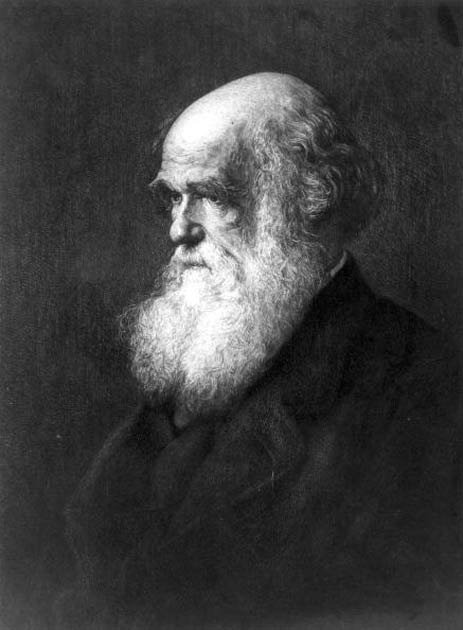

Evolution makes for inspired art

An exhibition exploring how artists have been inspired by Darwin's theory of evolution is the best of this year's anniversary shows, says Tom Lubbock

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How do you picture evolution? The images that come to mind are probably not works by any of Darwin's great artistic contemporaries. No, they're a couple of 20th-century cartoons. There's Rudy Zallinger's illustration, The March of Progress, which first appeared in the Time-Life book Early Man (1970). It shows a line of primates walking, from left to right, evolving step by step from a knuckle-dragging ape to an upright, modern, Caucasian man. You know it well. It's an image that's become proverbial, much quoted or adapted, familiar to multitudes that have never seen its original version.

The other cartoon is Walt Disney's animation, Fantasia (1940). In the prehistoric sequence that accompanies a drastically edited version of The Rite of Spring, there's an evolutionary episode. It starts with a ballet of undersea primal blobs. One of the blobs takes shape, and embarks on a journey, left to right and upwards, during which it mutates into more complex life forms – tadpole, fish, amphibian – finally surfacing as a primitive terrestrial quadruped.

These cartoons are certainly vivid and also (as it happens) highly misleading images of Darwin's theory. But they're not exactly art. And if 150 years after the On the Origin of Species there aren't any obvious examples of Darwinian art, you might suppose that there simply aren't any at all. So go to the new exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and think completely again.

Endless Forms: Charles Darwin, Natural Science and the Visual Arts is the most important and interesting of this year's anniversary exhibitions. It makes its revisionist case forcefully and sweepingly. From now on, Darwinian art will be a field of research and gradually a cliché. True, it would be odd if one of the intellectual revolutions of the 19th century had had no visible impact in its visual art, especially since it concerned things – nature, the human body – in which art had a long interest. But you weren't expecting to find, I guess, Degas, Monet, Cézanne, even Gauguin in this story?

The show takes a good look around. It begins by showing how British visual culture was already hospitable to the Origins. There were intense geology paintings (by Turner and Ruskin, among others). There were entertaining dinosaur scenes, including Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's clumpy, cuddly Extinct Animals, and Robert Farren's An Earlier Dorset (great title) displaying a battle of lake-monsters, laid out with a Look and Learn clarity. The empiricist vein in British art leads to frequent near-overlaps with scientific observation. And even Darwin himself, a self-confessed philistine, can do you quite a pretty diagram.

And then we're on to the wide repertoire of Darwinian themes, and the ways they feature in visual art. The struggle for existence, the adaptation of forms, mutation of species, links between animals and humans, facial expression, the lives of monkeys and apes, cavemen and tribesmen, sexual attraction and selection...

The argument proceeds quite straightforwardly, even though the pictures sometimes still anticipate the texts. We meet the struggle for existence in Edwin Landseer's paintings of mortal combat among stags. We see it at a social level in human destitution as pictured by Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer. And it's very striking to see these dark images of the victims of Victorian competitive capitalism, just across from Bruno Liljefors's Four Bird Studies, an image of nature's competitiveness in all its loveliness.

We then meet human-animal links, spelt out in Landseer's anthropomorphic portraits of dogs. (There's a bit too much Landseer.) And there is a clearly symbolic if clearly unhappy depiction of the whole business, in George Frederick Watts's Evolution. Humanity, a big mum, looks doomily ahead, as her babies squabble around her feet.

The missing links between Darwinism and art are sometimes a little tenuous. It's can be hard to isolate Darwinian themes from everything else. Hasn't art enjoyed a battle many times before? Hasn't it often been amused by the likenesses of humans and beasts? And as for an interest in sexual attraction, that hardly began in the Victorian age.

Or even if the connection is explicit, it can also be very free. Max Klinger's brilliant little engraving of centaurs, violently fighting in the snow over a dead hare, has a Darwinian scenario - primitive creatures, intermediate species, struggle to death – but totally mythologised. Odilon Redon's series Origines is a fantasy of metamorphosis, from blob to man, but with no apparent Darwinian pedigree in between.

The lesson of Endless Forms is that art can't be expected to strictly illustrate a theory, let alone convey it accurately. (What 20th century art did with relativity is just as loose.) We should really be talking about the Darwinesque, a dispersed cultural atmosphere, which contemporaries breathed.

Big ideas hang in the air, and artists – like most people – pick them up in a vague sort of way, and take them as support for things they like anyway. Darwin doesn't give much warrant to the cult of the femme fatale, but just enough for fin de siècle artists like Rosetti and Alfred Kubin to feel that science is behind them when they throw in peacock feathers as a mark of overt sexual display.

This gets most interesting, obviously, when the art gets good. Degas took an explicit interest in contemporary science and pseudo-science. His Little Dancer may embody ideas of degeneration and criminal physiognomy. Some contemporaries found her a bestial simian figure, even though we see her as more cute, and which way Degas felt it is hard to decide.

Or how about Cézanne's early The Abduction? Normally, this scene of a naked man carrying off a naked woman would be understood as an abstractly mythical vision. Is it really set in caveman world? (The subject was popular among other artists.) And Monet's paintings of rocks off the Normandy coast: should we see their rough and ragged profiles as poking up from the earliest eras of life on earth?

And then there's the culmination of this line of enquiry – sadly not hanging in the show, but discussed in the fine catalogue. I mean, Gauguin's panoramic allegorical picture, Where did we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Admittedly, I can't see much evidence of even Darwinesque notions, beyond the presence of primitive people. And the period had a load of ideas about spiritual progress on offer to inspire Gauguin. But still...

Perhaps the Darwinism in this picture isn't so much in Gauguin's imagery as in his colours. The show keeps its argument mainly on the level of subject matter, and understandably. Subject questions stay reasonably definite. But we should also be looking for a Darwinian look or sensibility or aesthetic. Its presence would be harder to indentify than themes, but it might be truer to the way art responds. It probably involves violence, a feeling of bursting life force.

A fusion of vitality, beauty and cruelty is something you find in Darwin's own writing – for example the words that give this Cambridge show its title: "Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death... endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved." Or there is the amazing bracketed phrase in his assertion "that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable." There is killing in nature and in the natural scientist's heart too. And Darwinism shows up in the forms of art as a marvellous murderous mutability.

I don't know how I would prove that. I don't know how I'd show that the searing colours of post-Impressionism and the breakdown of shapes in Cubism and early abstraction were part of this story, except to insist that art history must include things that can't be demonstrated; and that from the thought of Darwin these are among the endless forms that have been – and probably still are being – evolved.

"Endless Forms: Charles Darwin, Natural Science and the Visual Arts", Fitzwilliam Museum, Trumpington Street, Cambridge (01223 332 900; www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk) to 4 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments