David Hockney interview: 'I thought I was a peripheral artist, really'

The artist talks about his new paintings, distorted perspective and the afterlife ahead of his major retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in November

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When David Hockney began his career, figurative painting was considered old hat and even retrogressive. The assumption in advanced circles was that abstraction was wholly superior, raising large, lofty questions about the essence of painting instead of getting bogged down in the picayune details of postwar life. What possible wisdom could be gleaned from a painting that depicts a palm tree, for instance, or the glistening turquoise of a backyard swimming pool?

Hockney, who is often described as Britain’s most celebrated living artist, has painted those precise subjects and is well aware of the suspicions of triviality his work can arouse. Sitting in his studio in the Hollywood Hills section of Los Angeles, he recalls an amusing snub. He was visiting a gallery in New York, when he bumped into critic Clement Greenberg, abstract art’s most vociferous defender. “He was with his eight-year-old daughter,” Hockney remembers, “and he told me that I was her favourite artist. I don’t know if that was a put-down. I suspect it was.” He laughed softly, then adds in his gravelly, Yorkshire-inflected voice, “I thought I was a peripheral artist, really.”

Nowadays, in an age when the choice between abstraction and figuration is dismissed as a false dichotomy, and when younger artists imbue their work with once-taboo narrative and autobiography, Hockney is an artist of unassailable relevance. One suspects we will see as much when a full-dress retrospective of his work opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in November. An agile, inquisitive draughtsman inclined to careful observation, he has always culled his subjects from his immediate surroundings. His art acquaints us with his parents, his friends and boyfriends, the rooms he has lived in, the landscapes he knows and loves, and his dachshunds, Boodgie and Stanley. He is probably best-known for his double portraits from the Sixties and his scenes of American leisure, the sunbathers and swimming pools that can have a strange stillness about them, capturing the eternal sunshine of the California mind with an incisiveness that perhaps only an expatriate (or Joan Didion) could muster.

In the 1960s, Hockey was easy to recognise, a boyish figure with an apple-round face, a mop of blond hair and his trademark owlish glasses. Nowadays, at 80, he has grey hair, and he wears a hearing aid in each ear. “Every time I lie down, I have to take them out because they fall out otherwise,” he says. He is able to carry on a conversation amid the quietude of his studio but feels it is futile to head out with friends. “If you are going out in the evening,” he says in a slightly rueful tone, “you are going out to listen, and I am not very good at listening.”

His studio sits on a hill above his house, and the grounds are slightly riotous. As in certain Hockney paintings, large-leafed plants abound and exterior walls are painted in discordant hues of hot pink, royal blue and yolky yellow. An inflatable swan floats in a kidney-shaped swimming pool that itself contains a Hockney painting: an abstract composition with curving blue lines dispersed rhythmically across the surface, like a cartoon rendition of waves.

Hockney is still a dapper, vigorous presence. His conversation is wide-ranging and larded with literary references, and his manner is so genial and confiding that at first you do not notice how stubborn he can be. He delights in espousing contrary opinions, some of which come at you with the force of aesthetic revelation, while others seem perverse and largely indefensible.

In the latter category, you can probably include his regular denunciations of the anti-smoking movement. He smokes a pack a day and blithely discounts the hazards of cigarettes and cigars. “Churchill smoked 10 cigars a day for 70 years,” he tells me with apparent glee. “Well, nowadays, they tell you that cigars are the kiss of death. Churchill didn’t think so.”

Unlike other exiles, who typically bemoan chaos in their homelands, Hockney is still a British citizen and speaks about the Queen with unalloyed admiration. He is completing a 20ft-high stained-glass window for Westminster Abbey in her honour. He shows me his design for the window: a 10ft-tall inkjet printout inscribed with a lush floral scene. He composed it on his iPad. Its subject, he says, is the English hawthorne blossom, but to my eye, it appeared semiabstract and called to mind Matisse’s windows for his chapel in Venice.

Hockney, it might seem, is a direct heir of Matisse’s fauvism, pushing colour contrasts to trippy and hedonistic extremes. Yet when Matisse comes up, he is curiously silent. Perhaps the story of Matisse’s influence is so abundantly evident that he feels that there is nothing to say about it. Or perhaps he just feels more temperamentally aligned with Picasso, whom he does like to talk about and whose Cubism speaks to his obsession with the mechanics of vision. In 2001, Hockney published an important book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, which argues that advances in realism in Western art could not have been possible without the sly use of mirrors, camera obscuras and other optical devices.

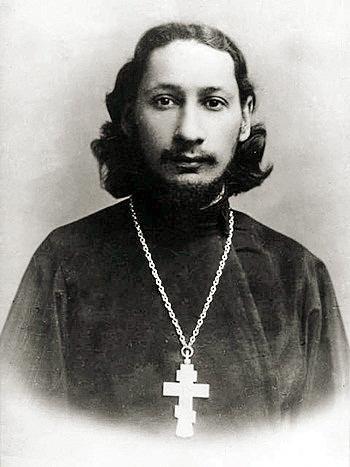

These days, in his newer paintings, Hockney is exploring the concept of “reverse perspective”, which poses yet another challenge to the accepted story of Western painting. Before my visit to his studio, he emailed me a recent discovery of his: a 105-page essay by Pavel Florensky, a now-forgotten Russian mathematician who died in 1937, a victim of Stalin’s goons. Florensky was also a gifted art historian, and his 1920 essay, Reverse Perspective, is a dazzling piece of revisionist criticism conceived in defence of 14th- and 15th-century Russian icons. He argues that correct perspective is overrated. The absence of perspective in Russian icons – as well as in Egyptian art and among the Chinese – was not a blunder but an inspired choice.

Elaborating on that theme, Hockney says: “In Japanese art, they never use shadows.” He takes out a book of woodblock prints by Utagawa Hiroshige and flipped to a page that showed a small wooden bridge arching across a powder-blue body of water. “There is no reflection,” he says. “Even with a bridge, there is never a reflection in the water.”

I looked up at the new paintings on the walls of his studio, wondering if he, too, had omitted shadow. Not entirely. The work still contains deep space and foreshortening, but the viewpoint keeps shifting. The pictures are riveting in their spatial distortions, and it’s as if they were saying, “to hell with the idea of a single vanishing point”. Most of the new works are painted on irregularly shaped canvases, whose bottom corners are sliced off, destabilising the rectangle and cultivating the rogue energy of diagonals. In one of his more engaging, not-yet-titled works, Hockney juxtaposes images of a disappearing road, a tuxedoed gentleman dancing toward you and a boxy pseudo-stage on which a portrait of a lion (a pun on “line”?) is displayed behind hot-pink curtains. “Just chopping off the corners has done wonders for me,” he says.

After a while, his chief assistant, Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, indicates it’s time for lunch. JP, as everyone calls him, is a bearded, taciturn Frenchman of 52 whose background is in music and the accordion. Hockney describes him as “my faithful companion of 15 years”. I asked them whether they intend to marry, and they replied in the negative. “Marriage is about property,” Hockney says, with his usual distrust of orthodoxy. “When you get divorced, you know...”

As we left the studio and headed down the outdoor stairway that leads to the house, the view of the garden was recognisable from Hockney’s paintings. He may like to articulate recondite theories about “reverse perspective” – OK, whatever. What makes his work memorable is not its devotion to technical questions but to lived experience. The new series began with Garden With Blue Terrace, from 2015, which captures the deck outside his living room as a giant chunk of aquamarine, angled to make it wider than life. On the right side of the canvas, jumbo-size green leaves seem to push forward from behind the railing, and the whole scene feels alive with the excitement that can come from getting closer and closer to the things you care about.

The new work was scheduled to be unveiled at the Pace Gallery in New York this autumn, to coincide with the Met show. Critics who have faulted Hockney for overproductivity should know that he didn’t finish the work in time. “I have to do the paintings!” he says.

In the meantime, a small, well-chosen show of earlier work – half self-portraits, half photographic collages – remains on view at the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, until 26 November. The show’s jarringly festive title, Happy Birthday, Mr. Hockney, can make him sound less like a daring modernist than a beneficent kindergarten teacher. But the intellectual ambition of his work is evident. The centrepiece of the show is Pearblossom Hwy, 11-18th April 1986, #1 a mural-size scene of a shining desert crossroads somewhere in southern California. A road sign admonishes “Stop Ahead”, but your eyes keep moving across the piece, which was assembled from more than 700 close-ups that Hockney took with his Polaroid camera in an attempt to extend Picasso’s Cubism into photography.

Hockney’s work is varied, maybe over-varied, but it does offer up a coherent worldview. If his entire oeuvre was buried in a mudslide and unearthed hundreds of years from now, a person looking at it might think that our age was actually an admirable one – a time when we placed a premium on our friendships, savoured nature and its splendours and promoted social tolerance. It is not irrelevant that he was painting portraits of his gay companions well before the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 decriminalised homosexuality in England.

One August evening, a few days after my visit to his studio, Hockney drives over to the Getty to participate in a panel discussion about his work, in front of a crowd of several hundred people. The event’s moderator, writer Lawrence Weschler, has forewarned the audience that there was no smoking at the Getty, unless you happened to be Hockney, who had been granted a special papal-like dispensation for the evening. Then, in a gesture that hovered ambiguously between a safety drill and a bit of surrealist theatre, a guard walks onto the stage sportily displaying a red fire extinguisher. The audience roars.

It is possible that the great subject of Hockney’s later work is landscape. He has occasionally traded the libertine vistas of California for the less sunny countryside of his native Yorkshire. In 1989, he bought a big red brick house for his mother and sister, overlooking the sea in Bridlington, not far from where he was born. “My mother lived for most of the 20th century,” he reflects, back in his studio, “and the first half was the worst half. The second half was much better. She began life rough and hard, and ended it in comfort.”

One of the highlights of the Met show is sure to be the landscapes he has painted in that area. He stayed on in the seaside house after his mother’s death, devoting himself to large-scale views of winding roads and the intricate woods of the Yorkshire Wolds. Some of the paintings have clouds and pale light, a sense of encroaching mortality, restoring the tenderness that had been bleached out of his earlier landscapes by the incessant California sun.

“My mother’s ashes were sprinkled on a lovely little road that ran from Bridlington,” he says. “At the end of the road was a Gypsy encampment, so not many people ever turned down this road. But we did. I think this life is a big mystery. And there could be another.”

Is he saying he believes in an afterlife?

“There could be,” he answers in an earnest tone. “I think about these things now. You could move to a new dimension. In mathematics, they now have 10 dimensions, 12 dimensions. Well, we only have three dimensions, four if we count time. But time is the great mystery, isn’t it? I think it was St Augustine who said if you ask me what time is, I do not know. But if you don’t ask me, I do know.”

As he mulled on time in the abstract sense, the day was getting on. I was curious to ask him whether he thought his new works represent an official “late style”, with all that implies about a break from the past.

“You don’t know what a late style is, actually, until it is finished,” he replies, taking another drag on his cigarette. “And the work is finished when you fall over. That’s what is going to happen. I will just fall over one day.”

The David Hockney retrospective is at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 27 November to 25 February 2018

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments