Why Damien Hirst's new Colour Space Paintings don't work: They are awful, and they look awful here, displayed amongst all this ancestral clutter

What is the problem with this arrangement? It is not that Hirst is hands off to the extent that he has chosen to be. It is that his ideas are not good enough

How do you draw the crowds to an old, landlocked house deep in the Norfolk countryside? Perhaps call on Damien Hirst. The seventh Marquess of Cholmondeley, Lord Great Chamberlain of England, owns Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s very first prime minister, commissioned it from celebrated architects Colen Campbell and James Gibbs. It was finished around 1750. The place looks and feels frozen in time.

Making art, ancient and modern, a feature of the house’s appeal began some years ago, when many works sold off by George Walpole (the first prime minister’s grandson) to Catherine the Great of Russia – she was assembling her great collections for what would become known as the Hermitage in St Petersburg at the time – were brought back to the house for a few months, and displayed in the great state rooms of Houghton Hall all over again, in the very places on the walls where they would once have been seen. That sale – an early example of the flogging off of “our national heritage” – caused a terrible stink in Parliament. George Walpole did it anyway.

The visiting season has just started all over again – it goes on for six months of the year – and Cholmondeley, all nervy smiles, in his slightly distressed brown corduroy suit and brown suede shoes (the laces are undone by the time he takes his leave of us a few hours later), with his grey, ageing, crotch-curious whippet in tow – is waiting by the door for the coach which brought the journalists up from King’s Lynn – there’s no easy way here by public transport. The coach is a luxury model, Mercedes-Benz, gold in colour, with a royal crest or two on its flank. Where is Hirst though? He pops by an hour or so into our visit, choppering down from the skies, though he doesn’t stay for lunch with the rest. His presence is felt a bit earlier on too, when someone is spotted getting this, that and the other out of the boot of a black, soft-top Bentley, which is parked, casually side-on, near to the stable block. Is that yours? I ask Cholmondeley, as I am gathering up my desert at the end of lunch. “I would it were,” he replies.

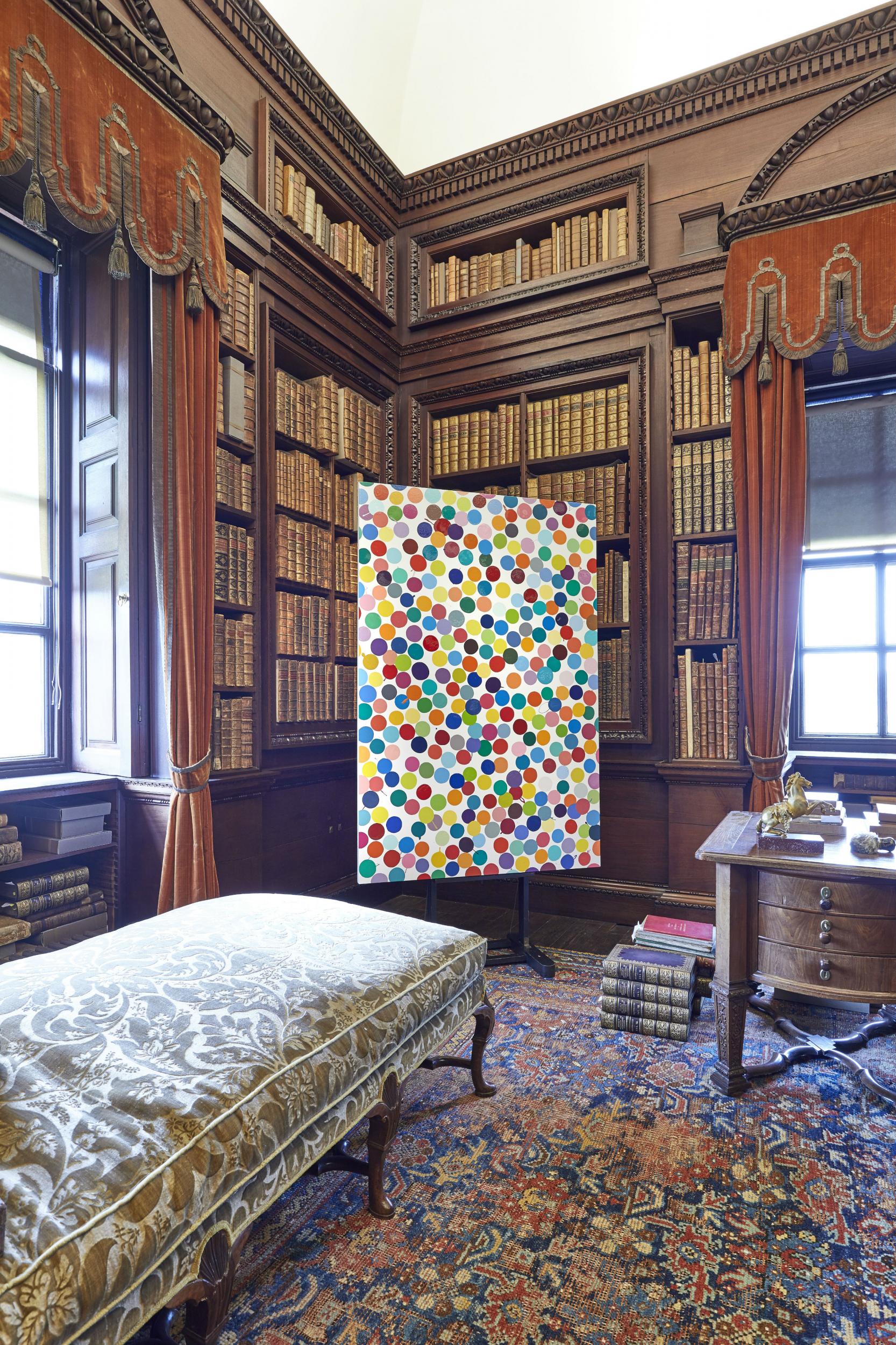

The presence of the art of Hirst here is manifested in two ways, through paintings and sculpture. The sculptures are indoors and out of doors, the largest of them – large enough to claim their slot on Easter Island – sited on man-made hillocks within a breezy walk of the house. They are fairground-freaky, upscaled giants in colours to shock and amaze. All the paintings are indoors, in the state rooms of the house, which turn in a square about the Stone Hall, the central courtyard. He calls them his Colour Space Paintings, and there are 270 of them in all (only a small selection of them are here) – a finite number, you see. You could call them the younger offspring of his Spot Paintings, which are potentially infinite in number because he has decreed that the series shall never end. This series does end. In fact, it has ended.

When I look at them, hanging on the walls of these rooms, occupying the spaces that the family portraits usually occupy, although often much smaller (which means that you can often see behind, to random hooks and pin marks against grubby canvas backings), peeking out beside grand, four-poster beds or jostling for our attention with a suite of tapestries in praise and commemoration of the Stuart kings, I feel rather relieved that the series is finite in number.

Why? Because they are awful, and they look awful here, displayed amongst all this ancestral clutter. They are utterly uninteresting as works of art. They are both like and unlike the Spot Paintings. In fact, they are Spot Paintings of a more rough-and-ready, slightly more anarchic, pinball-machine-ricocheting-around kind. There are no grids to hold them together. The dots, slightly imperfect circles of varying sizes, fabricated in paint which possesses an outstandingly ugly sheen, sometimes overlap each other a bit. They jostle around. They crowd each other out. They drip a little when the mood takes them. All these works were made in one or another of Hirst’s three studios, by one or another of his anonymous studio assistants. Successful artists have often had studios with assistants. The quality of the work is entirely dependent upon the quality and the nature of the artist’s input. What is the problem with Hirst’s arrangement? It is not that he is hands off to the extent that he has chosen to be. It is that his ideas are not good enough.

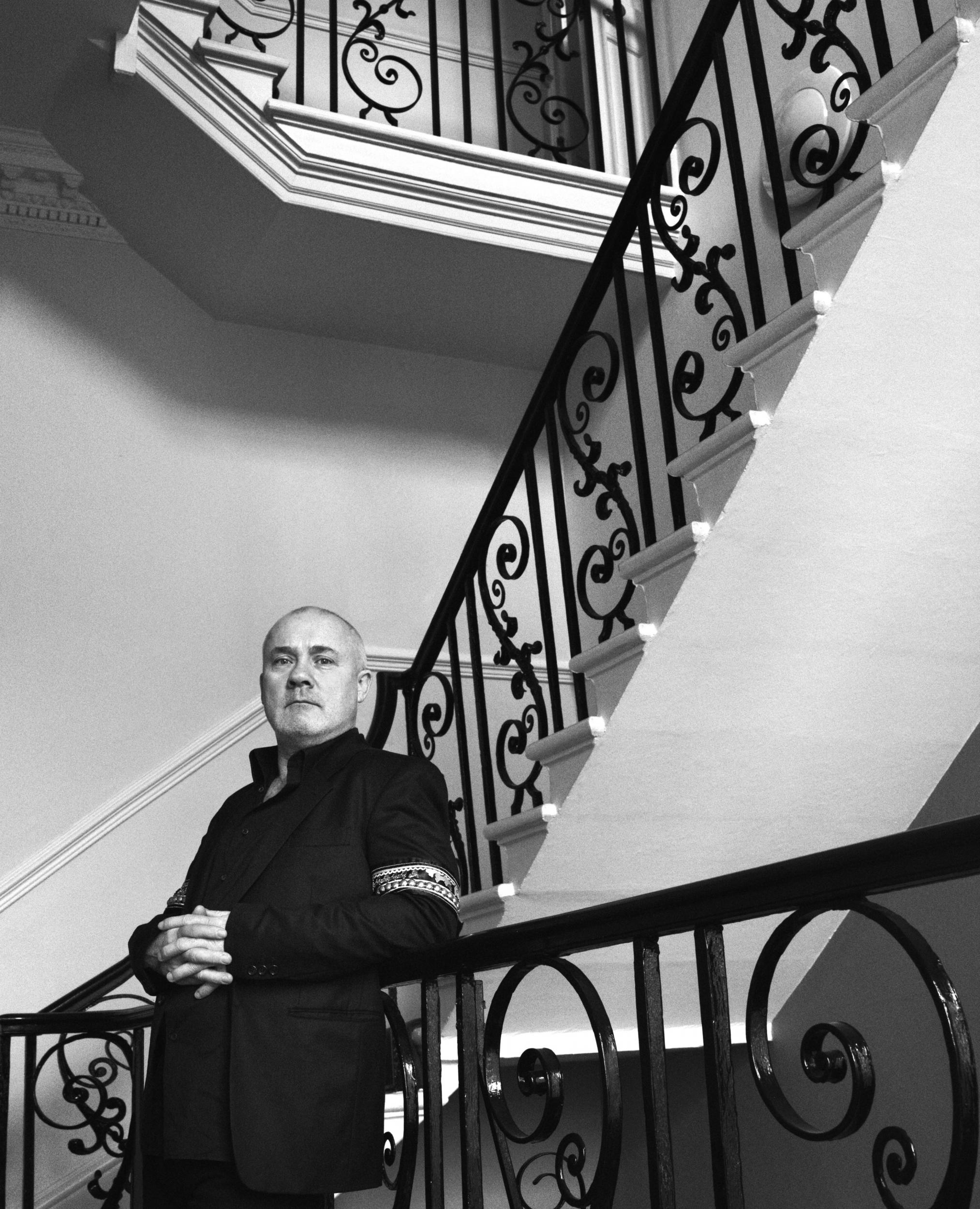

We stand with Hirst and listen to him praising them. He is as good-humoured as ever, bullishly confident, with long, heavy chains around his neck, blue shoes, and, well, almost hairless these days too, no longer the enfant terrible, more the homme vieillissant assez terrible, a man in his sixth decade, powering along towards infinity.

You don’t want perfection when you are getting old, he quips. We are all falling off the grid a bit.

“What did you think?” Cholmondeley asks me as I leave the table with the buffet. “I think it’s a hoot,” I tell him. “That’s it, yes,” he replies, it’s a hoot. He looks terribly pleased that we can shake on that. He’s put on a good spread too, bless his ancestral suede shoes: Houghton Hall Traditional Claret courtesy of Berry Brothers of St James’s Street, fresh pressed and bottled apple juice from the trees in the walled garden of the house. The monogrammed porcelain luncheon plate from which to smooth-lift the ham to the mouth. The gilded coach.

It’s all almost guaranteed to raise a huge critical cheer.

‘Damien Hirst at Houghton Hall: Colour Space Paintings and Outdoor Sculptures’ until 15 July (www.houghtonhall.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments