Court artists: Quick on the draw

A slew of celebrities in the dock has put the spotlight on the arcane art of courtroom sketches

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Priscilla Coleman woke up early yesterday morning and got on the train to Preston. As one of the three main court artists in the UK, she was to sketch the scene at the trial of Bill Roache, the Coronation Street star accused of sexual assault. The day before, Coleman had been at the Old Bailey for Jude Law's appearance as a witness in the phone-hacking case, followed by a quick dash to Southwark Crown Court for Dave Lee Travis's trial (again, for alleged sexual assault).

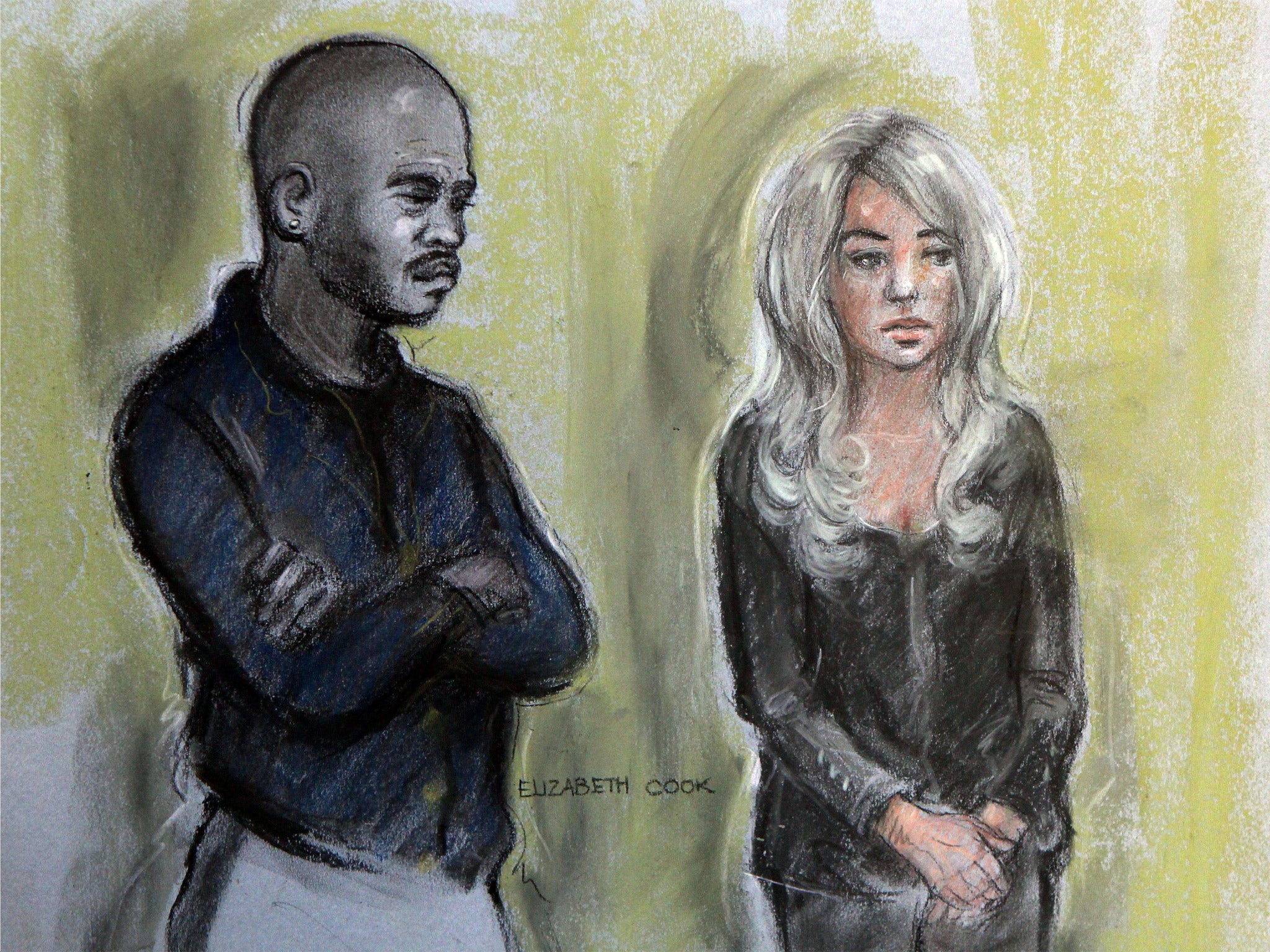

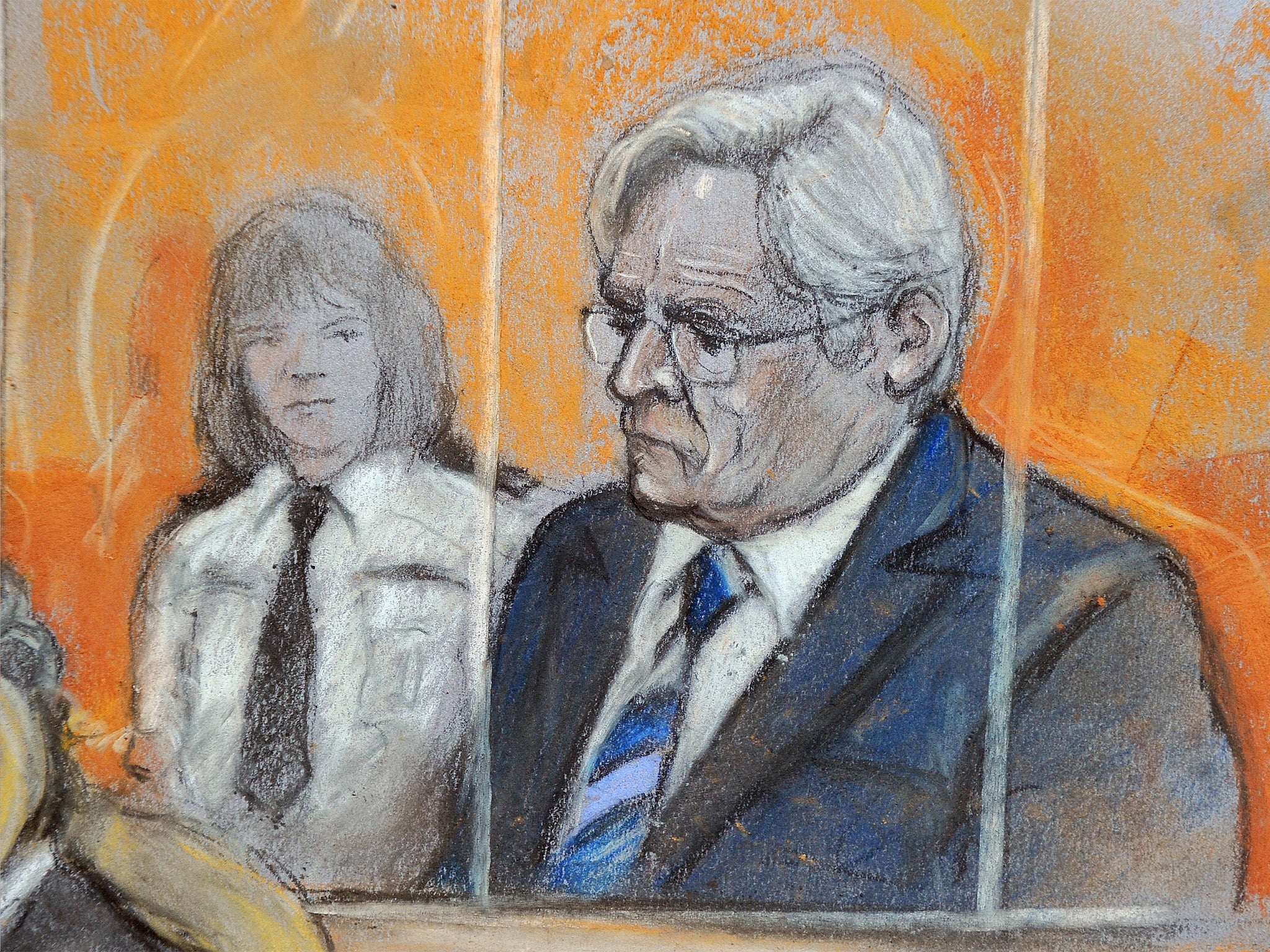

With both the phone-hacking trial and Operation Yewtree hogging the headlines, Coleman and the other two artists, Elizabeth Cook and Julia Quenzler, are much in demand. But it's not always this way; a major story outside the realms of the courts can mean that the media won't cover cases and have no need for sketches. Not great news when you're being paid by the day.

"During the Gulf War, no one was interested in anything else," recalls Coleman, a court artist for more than 20 years. "There were fascinating, important court cases going on, but the news couldn't really fit them in."

However, with plenty of famous figures now appearing in court, it follows that artists' impressions are in wide use in the media. This week, many observers found the drawings of Jude Law to be rather amusing, with Twitter users likening sketches of him by various artists to "Gary Kemp as Tintin", "some guy who hates his job at Telstra", and "Tony Blair".

What most don't realise, however, are the conditions in which the drawings are completed. Artists are not allowed to sketch in the courtroom; they spend a little time observing (usually from the journalists' bench) before leaving to begin the image, using written notes and memory. Cook, a court artist since 1992, might spend a few moments in court ("I can be in and out in a couple of minutes") before taking about 15 minutes to sketch each person.

"It's rolling news, so it demands instant pictures," she says. "The media outlets want them stuck outside the Old Bailey as quickly as possible. My work is very fast."

And working on an already familiar face does not make it easier for artists. Celebrities, Cook says, are the hardest to draw. "We're used to seeing them smiling on television, all animated," she explains. "When they appear in court, they don't have the same demeanour. It's quite hard to make the person recognisable as the bright and smiling celebrity that everybody is used to seeing on screen."

Court illustrators often make little mistakes and judges and barristers will joke that the artist gave them the wrong glasses, or extra chins. And it would seem that these kinds of jokes are welcome. "Light-hearted moments are few and far between," notes Cook. "I attend trials that really are the most extreme. I hear the worst things as the evidence unfolds. I'm constantly aware that I'm sitting in on someone else's tragedy."

Of course, advances in technology are changing courtrooms. Cameras were allowed into the Court of Appeal last October and are expected to be used more frequently. Artists are under no illusions about the threat this poses to their livelihoods. "I'm assuming it's going to happen soon – they've been talking about it for years," says Coleman. "I'm not sure what I'll do. There's always a need for artists, though, isn't there?"

As Cook points out: "The judge doesn't write with his pen and ink any more. He taps away on his computer. Stenographers were phased out in 2012. All the barristers bring in their laptops. Journalists are allowed to tweet in court. We're becoming so technologically aware that some might view the person who goes in to do a drawing as a little outmoded. But there's a charm to the pictures."

There is indeed. And if Jude Law feels a little hard-done-by in his courtroom pictures, he should take comfort from the fact that, according to Cook, "good looking people are surprisingly difficult to draw."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments