Cartoonist Art Spiegelman: 'I don’t want to spend another 13 years on a book'

The American cartoonist, whose graphic novel ‘Maus’ won a Pulitzer Prize, has been determined not to let comics fade as a mass medium. Now he has written an introduction to Si Lewen's wordless novel ‘Parade’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

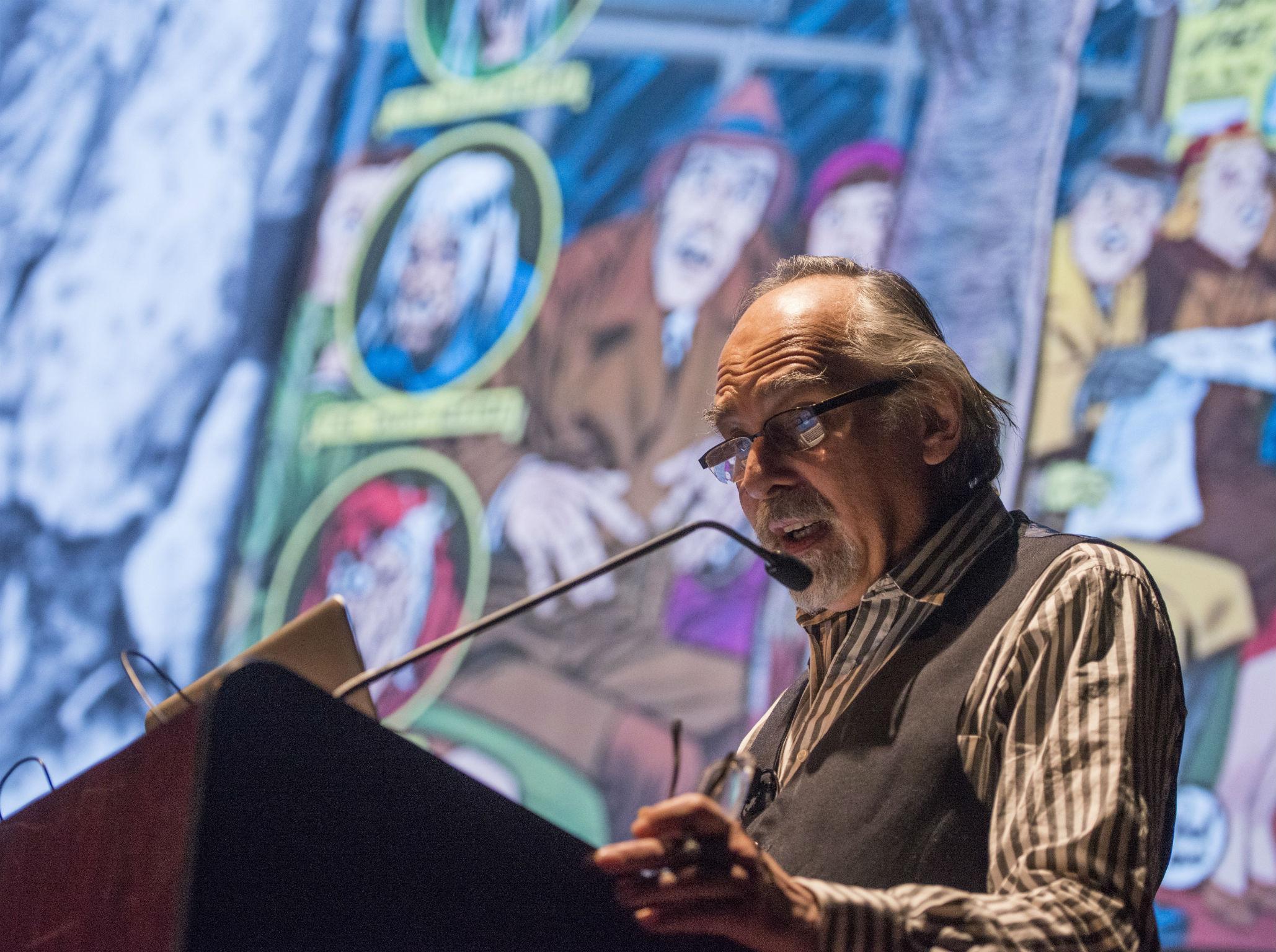

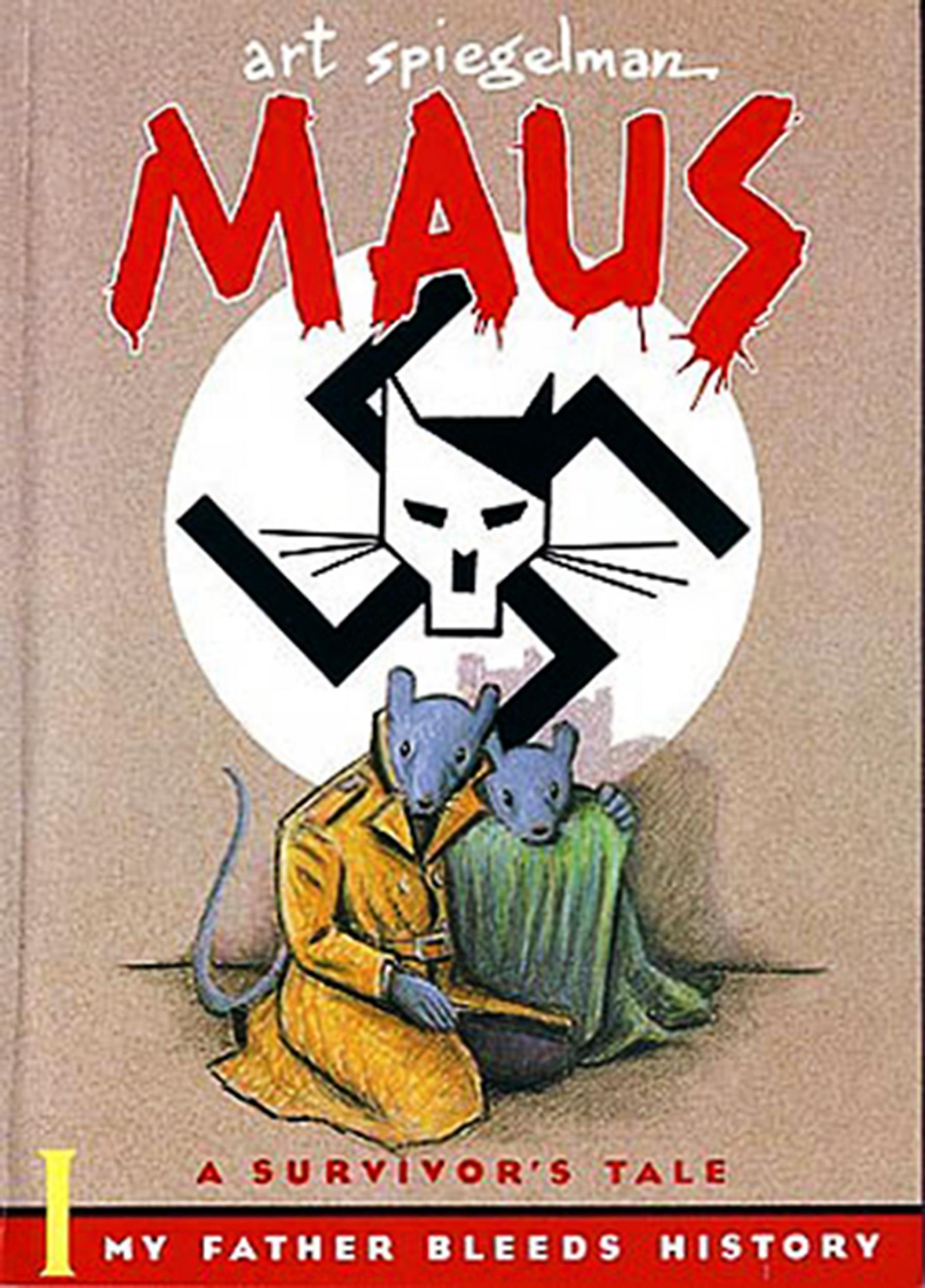

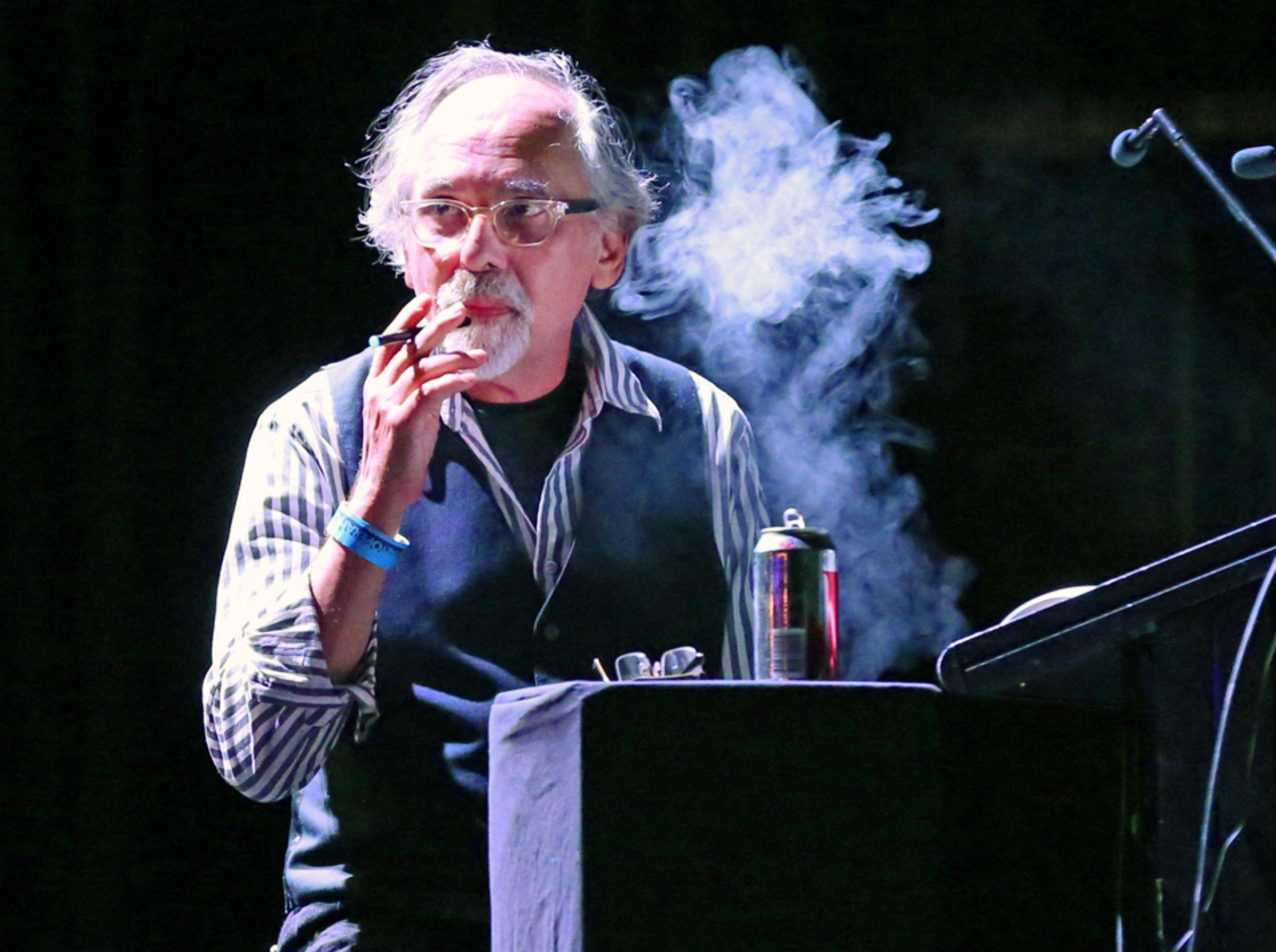

Your support makes all the difference.“I seriously worry all the time,” the cartoonist Art Spiegelman says, days after Donald Trump becomes President-elect. “It’s my nature. But here – eureka! – I’ve finally found something worth worrying about!” He laughs grimly. “And I also can’t help but see parallels to the Thirties and Forties wherever they’re to be dug up, to a degree.” Still, the “underestimated, clownish” Trump seems a horribly familiar phenomenon to Spiegelman whose Pulitzer-winning graphic novel, Maus, described his father’s survival of the Holocaust.

“I see something similar to Hitler,” Spiegelman continues, “in that it’s gone very fast to things that seem surreal to me, like Trump supporters shooting four civilians at a polling place in California – one of them died. And there’s the slide towards uncivility, from what I read on the internet. For the first time I got to see my name with three parentheses signs around it. I don’t think it was a secret that I’m Jewish, but they were making sure that the alt-right people would know that I was Jewish. That’s just something I saw a couple of days ago. ‘Oh, I see. OK, it’s a new day.’ And at this point we don’t care about refugees’ lives. They’re not white lives. So yeah, sure, I’m worried.”

We’re talking in Spiegelman’s London hotel, a warren where he gets regularly lost. His words have a gently eager flow, taking pleasure in intellectual communication laced with quick, dry wit, and a refusal to mollify what he thinks. These same qualities make the tough subjects of his best-known comics, from Prisoner On Hell Planet's memoir of his mother’s 1968 suicide to In the Shadow of No Towers, which explored the 9/11 attack 10 blocks from his family’s home and their flight from its toxic black cloud, effortlessly readable.

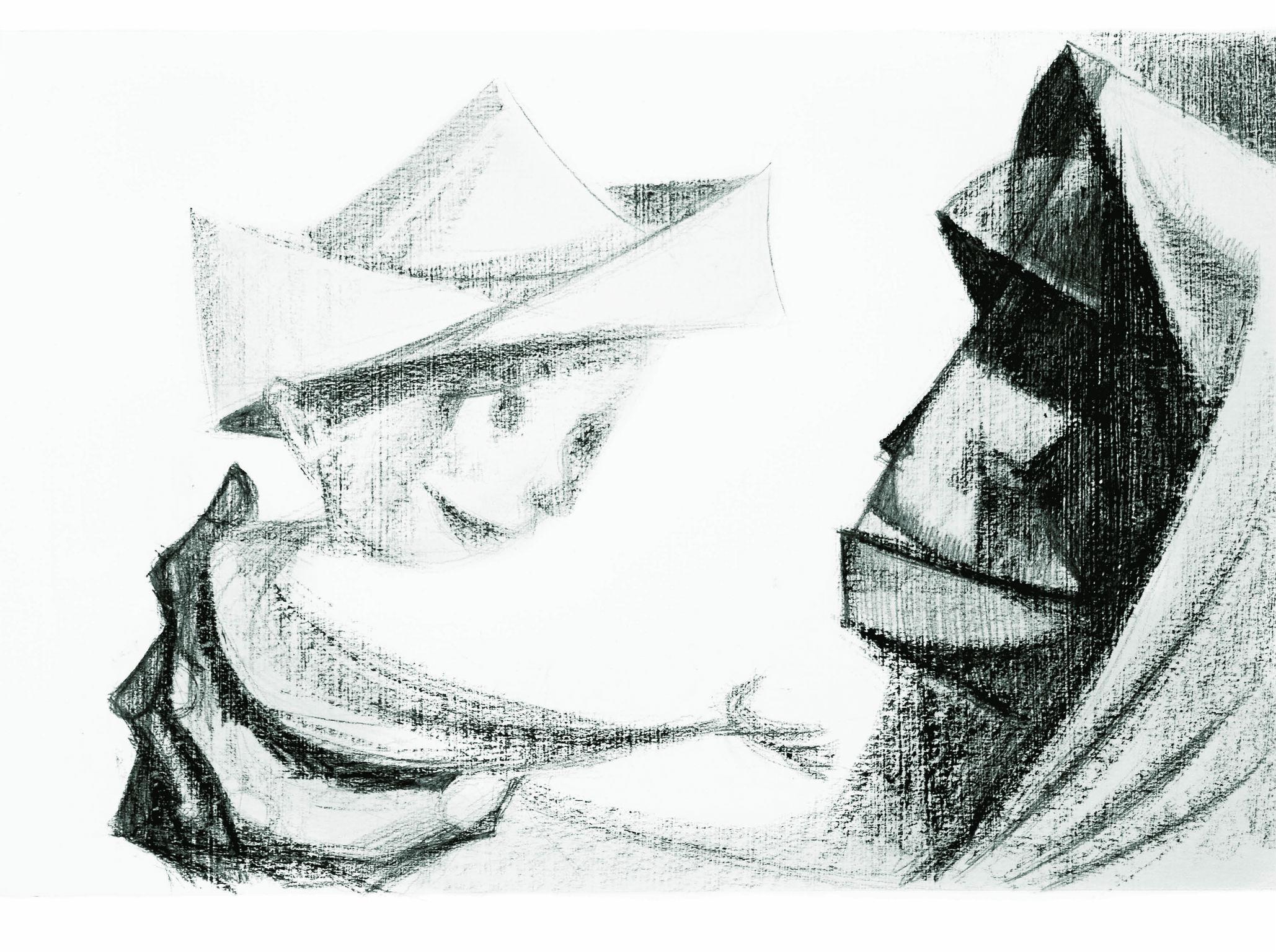

He hands me his latest project, Si Lewen’s Parade, a slip-cased book which concertinas out, with Spiegelman’s essay on Si Lewen lavishly illustrated with the artist’s paintings on one side, and the Albert Einstein-endorsed The Parade, Lewen’s 1951, wordless novel on the other. “The Parade’s about our generational dance through war toward death,” Spiegelman says, lovingly turning its pages, “and exhausted, we drop out of the dancefloor to get enough energy to kill each other again. It feels especially important at the moment.”

Lewen died this year, just short of his 98th birthday, leaving Spiegelman, now 68, time to befriend a man he found much in common with. “For one thing, absolutely his traumatic life,” he laughs, “which included being at Buchenwald a few days after it was liberated. He had gone from Normandy to that, and then with all the concussions and internal bleeding that he had, he came undone. He had been moving on Schnapps the whole year.” Back in the US, Lewen compulsively sublimated the horrors he’d seen in gorgeous, bright paintings which made him rich, till he turned his back on the commercial art world. “I also feel a kindred connection to Si in the fact that he didn’t do what was expected of him. I really admire the courage and eccentricity it takes to say, ‘Well screw that, I want to do this.’ And even in the old age home, he was painting all the time. I miss him, but I’m glad we made this book together.”

We’re a stone’s throw from the Barbican, where hours later Spiegelman and a jazz band, Phillip Johnston’s Silent Six, will help open the London Jazz Festival with Wordless!, in which they explore wordless novels, the graphic novel’s respectable ancestor. The packed-out crowd for a lecture about this now entirely obscure work shows the stunning triumph of the “Faustian pact” Spiegelman says he made in the 1970s, when he saw comics fade as a mass medium and, to ensure their survival, resolved to get them into museums and bookshops. Maus, which interwove his strained relationship with his dad Vladek with his parents’ experience of the Holocaust, culminating in Auschwitz, ensured his success.

He couldn’t find the time to participate in The Last Laugh, a new documentary about changing attitudes to jokes about the Holocaust, as it slips from lived experience into history. “I remember hating [Roberto] Begnini’s film [Life is Beautiful],” he considers. “He said he’d been inspired by Maus, and I thought, ‘Oh, shit. I wish someone would’ve taken the book away from him.’ That film’s obscene. And more and more, there’s a freedom to hallucinate on the Holocaust because it’s become an abstraction, not a real event. Maus, oddly, was using abstractions [by drawing its characters as animals] to make it real. I never did it to make the world better. It didn’t occur to me that it even could be made better, because it just does its own horrifying thing over and over, and thereby becomes lived experience again. But I was hoping, if one has an empathic response through art, that it allows one to absorb an experience so it’s no longer somebody else, but it’s you.”

“I don’t want to spend another 13 years on a book,” he says, reflecting on the lack of a real follow-up to Maus since its 1991 completion. “I don’t have that other book obviously in me. I spent the first few years after Maus trying to figure out what that might be.” Now, after that 300-page, epochal work, he’s contemplating “the one-page graphic novel…more filled with implication than any page has a right to be”.

Spiegelman’s French-born wife, Françoise Mouly, has been a relatively silent partner in his creative life since their 1977 marriage. She published, co-edited with her husband and personally printed parts of Raw, the influential comics magazine which serialised Maus in the 1980s, and since 1993 has been art editor of The New Yorker, where Spiegelman was a brilliant and controversial cover artist and cartoonist. They seem creatively symbiotic. “Absolutely. Symbiosis doesn’t mean lack of quarrels,” he laughs, “but we’ve become more ourselves, and more extensions of each other. I’m grateful not to be doing weekly New Yorker covers any more, I’m glad that she’s doing such a great job on it, and I can afford to get lost in follies like Si Lewen’s Parade. There’s no difference between our political and personal lives, so we have a lot to talk about. David Sedaris once said this funny monologue about him and his partner being worried they won’t have anything to say to each other, so they fill out index cards, with interesting places to go conversationally! Françoise and I don’t have the time or need for index cards, and that’s kind of swell.”

Spiegelman’s sensibility was forged by his mentor Harvey Kurtzman, whose creation Mad introduced the satiric attitude which, Spiegelman believes, let his generation question the Vietnam War. The 1960s, though scarred for him by a nervous breakdown just before his mother’s suicide, began his involvement with Robert Crumb and others in the taboo-smashing underground comics scene, whose attitude he’s kept. Is he nostalgic for those days?

“There’s something important that got lost. It came back with Occupy Wall Street for a second – that belief that change, not necessarily nihilistic change, is possible. Idealism, I think that’s the word I’m looking for. I suppose it’s coming back as its monster, Portrait of Dorian Gray double with Trump. I’m still trying to figure out what that Sixties thing was. There was an auction of rare underground comics the other day. And I was looking at it and I couldn’t remember the impulse that would have made us do it, because if you did it now, you’d just burn it immediately. It's racist, sexist, you’d be put in the stockade. I can’t really remember why we even did it – except I do remember how good the release felt of getting those things out of our heads.”

Spiegelman is in outspoken, considered despair at the tone of movements such as Black Lives Matter, “this PC vigilance and self-righteousness, often born of really good intentions, which just fed into Trump’s smears and this yahoo thing [going on] in America now of, ‘They can’t tell us what to do.’” The British left’s fear of offence meanwhile led to the New Statesman deciding not to publish a Spiegelman cartoon. “I had two little stick-figure drawings. One said, ‘OK,’ and the other, with a turban and the word Mohammed, said, ‘Not OK’. It’s not the obligation of a society that lives on and breathes icons to give fealty to the anti-iconic.”

Spiegelman passionately advocates desperately needed visual literacy instead, “a missile defence system” against the internet’s unparalleled bombardment. “The internet’s a Pandora’s box, you can find anything in there – well, maybe not hope,” he laughs softly. “But it does take anything to be true, in the most useless way. Man, it’s horrific,” he says, considering the times we now face. “Because in all of these things I see genuine echoes of the Weimar years, and that turned into something uglier and uglier.”

'Si Lewen's Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey' by Si Lewen with an introduction by Art Spiegelman is out now from Abrams ComicArts. The London Jazz Festival continues until 20 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments