Cadmium: The rare paint pigment faces a Europe-wide ban and artists are seeing red

Animal studies have shown that cadmium pigments can be potentially toxic if inhaled or eaten

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s the paint pigment that brightened Monet’s autumn leaves and Matisse’s red studio.

But there are dark times ahead for cadmium, which was also beloved of masters including Cézanne, Dali and Bacon. The rare metallic element faces a Europe-wide ban thanks to its potential toxicity, and modern artists could be denied the power and vibrancy – cadmium’s colours soar from pale to golden yellows, fiery to deep oranges, and from scarlet reds to maroon – of the hues used by past masters.

Allia Rizvi, the brand director of Winsor & Newton, which makes fine art products including cadmium paint, says: “Cadmium is of historical and modern day importance. It was developed at a time when some pigments were toxic, and it was quite a revolution.”

Cadmium was discovered by Friedrich Stromeyer, a German chemist, in 1817, but it did not become commercially viable for another two decades. The pigment was used sparingly because of the scarcity of the metal, which was reflected in its prohibitive cost.

“It was seen as revolutionary as it was so powerful. As soon as it became commercially available it was quickly adopted into the artist’s palette. And it still is a very strong part of professional artists’ palettes today,” Rizvi says.

The pigment is associated with oils, the medium largely used by the masters, but it is available in acrylic and watercolour paints as well. It remains one of the more expensive pigments: a 37ml tube of cadmium costs £17.85, (compared to a basic black or white at £7.15).

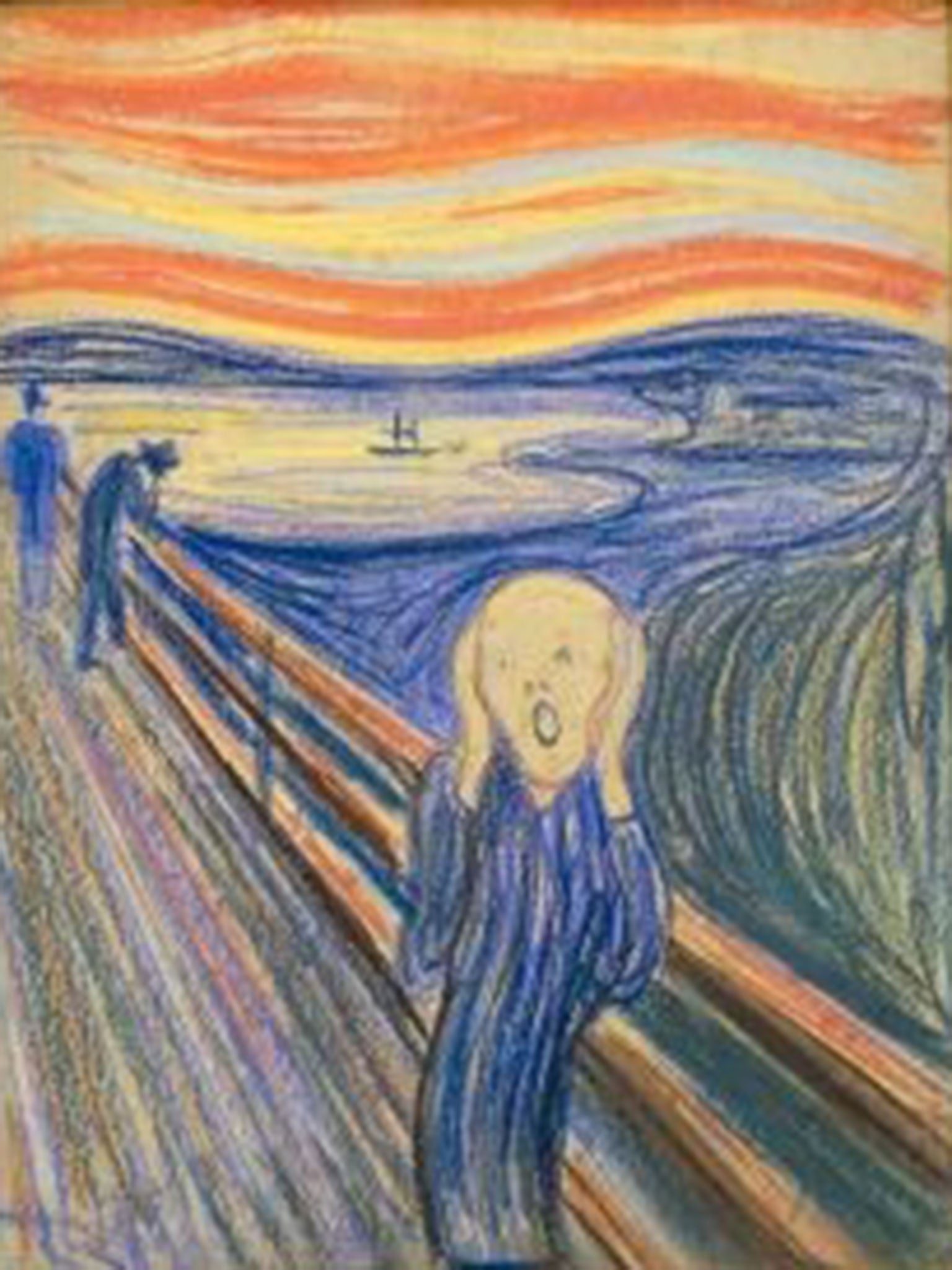

While Max Ernst, Joan Miró, René Magritte and Paul Gauguin used cadmium paint, Monet was particularly associated with the pigment in such paintings as Autumn at Argenteuil and the Water-Lilies and Irises that hang in the National Gallery. He was especially keen on it as he believed it would help his work last longer. “Cadmium pigments are light fast which generally means they won’t fade for 100 years or longer,” explains Rizvi. Yet experts have pointed to the fading in Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and Edvard Munch’s The Scream, with some blaming the cadmium pigment’s reaction to the air.

Meanwhile, cadmium and its adherents face a bigger problem as it faces a ban in the European Union while the European Chemical Agency considers a complaint from one of the member states. Sweden called for the ban, the Art Newspaper has revealed, over fears that when artists rinse their brushes in the sink, cadmium enters the water treatment plants and thus seeps into the waste sludge. That sewage is then spread on agricultural land and the Swedish government fears people will become exposed to cadmium through food.

Animal studies have shown that cadmium pigments can be potentially toxic if inhaled or eaten, but Michael Craine, the managing director of Spectrum Artists’ Paints, says that the cadmium used in the art world is not classified as hazardous and is of low solubility “to make the small risk smaller still”.

The public consultation that ran for six months into the issue closed last week. Craine says: “The worst-case scenario is that cadmiums could have disappeared within a couple of years, which in the view of many of us in the industry is both distressing and entirely unnecessary.”

Craine says that cadmium had found its way into landfills and water courses but this was because of nickel cadmium batteries. “Cadmium will have been banned unnecessarily; artists have been hit by a punch that was intended for a bigger fight. Cadmium is not used by amateurs, it is used by professionals who take great care and the product is expensive. Artists are not polluters, it is coming from other sources,” he says.

Many artists have signed a petition against the ban. The landscape painter Emily Faludy says that it would be a “disaster” if she was unable to use cadmium paints. “Often they are simply essential” she says, adding that it is “sunshine in a tube”. Fellow artist Michele Del Campo agrees, saying there are no valid alternatives.

The only organic alternatives – dubbed “cadmium hues” – largely fail to measure up to cadmium’s vibrancy. Janice Robinson, of the European Council of the Paint, Printing Ink and Artists’ Colours Industry, says: “They are indispensable to artists to create works of art with bright colours. Many of the beautiful Impressionist paintings of the 19th century would look very different today without their cadmium-based yellows, oranges and reds.” And a world without such works would be a very dull place indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments