‘There is a lot of hard work to be done’: How the art world can step up for Black Lives Matter

Events following the death of George Floyd have motivated the creative industries to look within, but many galleries and cultural institutions have stayed deafeningly silent. How can they move forward? Curator and writer Aindrea Emelife writes a powerful mission statement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dear art world, we have a problem.

In the days after the death of George Floyd, my Instagram feed began to fill with images that were different to the usual fluffy skirts of Monet or Koons’s jewel-tone balloon dogs, posted by art-world chums. They were replaced with frequent appearances of powerful artworks by black artists: David Hammons’s African-American Flag or Glenn Ligon’s neon light spelling “America”. But curiously, these images seemed not to be coming from the institutions where these artworks are held. The cultural institutions, the galleries and museums, were largely silent; many taking up to a week to respond to the social debate, some still yet to respond at all.

The resurgence of Black Lives Matter is inspiring many industries to look within and do better. After various calls to action from activists and artists, promises for change rippled through the art world. Hauser & Wirth, a blue chip gallery with a diverse roster of artists, posted their commitment to searching for solutions; other galleries vowed to audit their systems and evaluate steps for change. Tate posted a picture of Chris Ofili’s No Woman No Cry painting while outlining their duty to speak up for human rights and anti-racism.

Some settled for Martin Luther King quotes.

But a week past the announcement of Floyd’s death, as protesters marched in the streets, I still saw museums posting William Holman Hunt paintings as if the world wasn’t on fire with humanitarian debate. What was, and is, happening was impossible to ignore. It is a difficult and uncomfortable issue to address on social media, but putting in the time and research on how to address these issues is important. The art world can do better than virtue signalling – after all, doesn’t art hold truth to power and justice?

“I don’t think all institutions are being performative,” says Jasmine Wahi, the Holly Block Social Justice Curator at the Bronx Museum in New York. “But I do think that there is a lot of hard work to be done. I’d rather see the fruits of that labour later than hear about a plan ahead of time.”

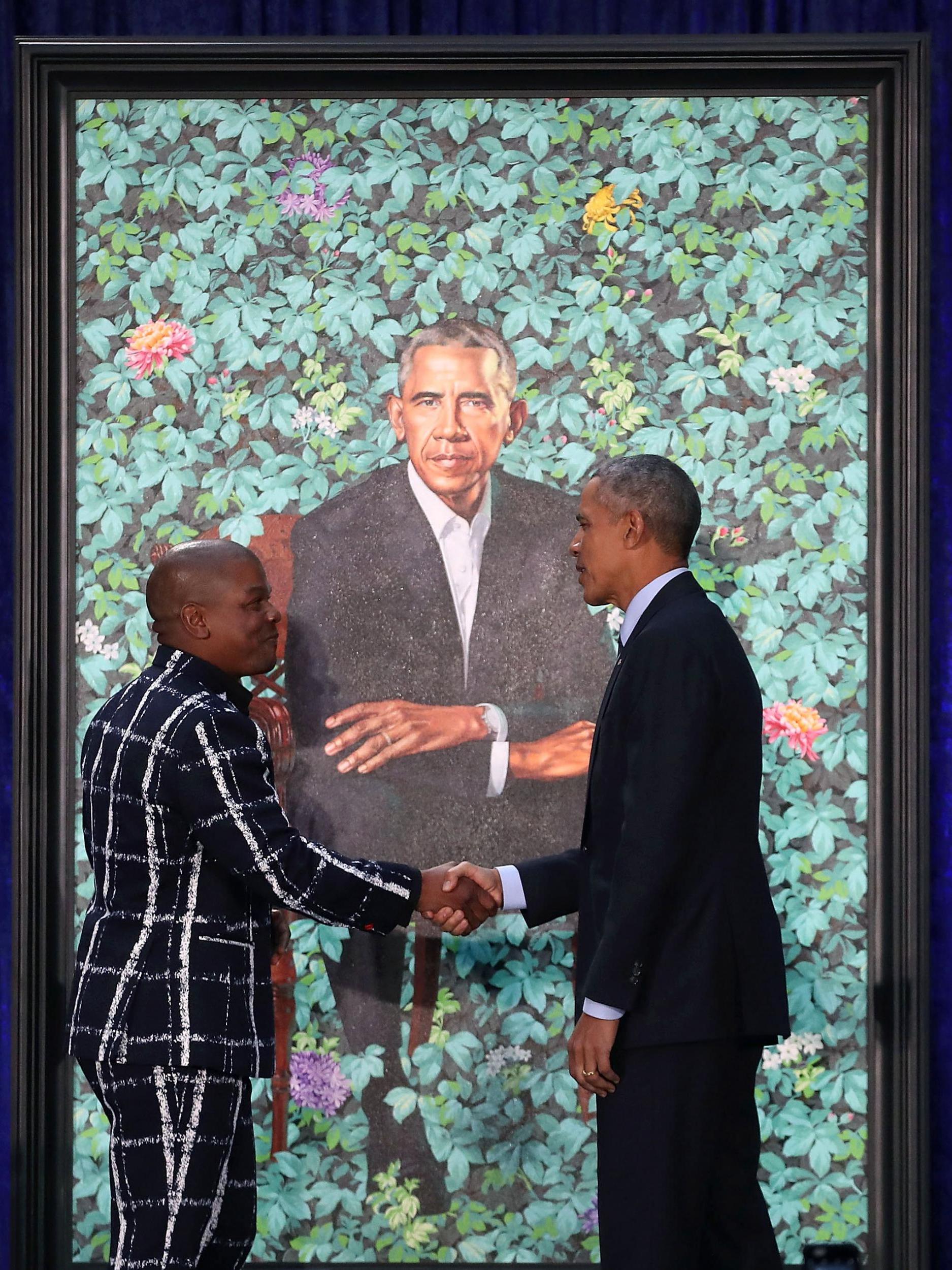

Perhaps the art world thinks it’s enough that visibility for black artists is incrementally increasing. Hey, there have been some blockbuster shows and Basquiat retrospectives and auctions breaking records. The roll call of the past few years in the US and UK includes Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald’s official portraits of the Obamas, Martin Puryear representing the US at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the Soul of a Nation show at Tate Modern, and Sonia Boyce getting set to represent the UK in the 2022 Venice Biennale – the first black female artist to do so.

But we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back just yet. A report in 2018 concluded that just 2.37 per cent of all acquisitions and gifts and 7.6 per cent of all exhibitions at 30 prominent American museums had been of work by African-American artists in the preceding decade. It’s a pitiful number, considering that African Americans make up more than 12 per cent of the US population and are creating some of the most compelling art and narratives of our time.

In the UK and Europe, meanwhile, Eva Langret, artistic director of Frieze London, says that “the arts industry embraces the success of African-American artists whilst still ignoring the work of black/POC artists locally”, allowing us to “shy away from our history of racism, while we scrutinise the American narrative”.

In fact, the Black Artists and Modernism National Collection Audit, led by Dr Anjalie Dalal-Clayton, has found that there are actually around (just) 2,000 works by black artists in the UK’s permanent collections – but most of them are not found on display. The place where real change begins is in the storage units. What museums have and acquire into their permanent collections matters because museum acquisitions form the canon of black art.

Similar conversations surrounding female artists have garnered attention, though recent data about the acquisition of art shows that there is still major work to be done. A 2019 report found that 11 per cent of all acquisitions and 14 per cent of exhibition programming were attributed to female artists within American museums. Of this small percentage, only 3.3 per cent are African American. If the visibility of the great female artists is still an uphill battle, the pursuit of black artists is Sisphyean.

Museums are supposed to be leading cultural discourse, and so they need to embrace culture in its entirety, expanding the demographic on the walls and through the doors, if they wants to make any meaningful change. “One of the reasons the racial bias is so endemic is because most, but not all, institutions were founded with a type of audience and agenda in mind and to preserve a type of history,” says Wahi. That history, she continues, “is only now being reconciled and recognised as singular and exclusionary”.

The pursuit of equity and magnifying varying voices is not just a matter of duty, nor is it just an exercise in reflecting demographics and numbers – it is a key tool to ensure museums’ relevancy in an ever-changing world. If art is truly “for everyone”, then “everyone” needs to be able to see themselves within art. We must educate and inspire the public, not just subscribe to established tastes and the spectacle and awe of fame or genius.

Osei Bonsu, curator of international art at Tate Modern, says that even when black art enters the museum, the narrative has been set. “If you look at the historical development of the Black Arts movements, both in Britain and the US, artists were searching for ways to imagine a space where black subjectivity could be articulated, expressed and signified outside of the frame of the white gaze.” For black art to enter the museum, he continues, those artists had to use the language of western art history – figurative painting – as a means to join and subvert the artistic narrative. “It was often about asserting the black presence within painting as a means of writing people of colour into an elitist and deeply codified art history,” he says.

That’s one reason why, as Langret says, it’s crucial to have an increase in black curators, art historians and gallerists in order to recontextualise narratives, amplify voices and address “black bodies trapped in white imaginations” – something I have come to feel deeply, as one of a very small pool of black art curators and writers in the UK. “Many arts organisations still mostly work with black/POC artists only within the context of discourses on race and identity,” she says. “As a result, there is a certain lack of nuance when it comes to integrating our voices within wider artistic discourses. Not all black/POC artists make work about race or figurative work that shows black figures. If there was more diversity within the curatorial staff, there would also be more diversity in how black/POC practices are (re)-presented.”

So, how do we tackle the issue? The argument for maintaining an emphasis on merit has been a frequent response from many when discussing diversity inclusion policies. “It’s a myth that there is currently a meritocracy within any institution,” says Wahi. “I don’t believe in ‘filling quotas’ to fill quotas, but the critique of that methodology discounts the fact that there is a basic threshold for talent. It asserts that the only criteria for getting those coveted jobs are race, which is absolutely and unequivocally untrue.”

Indeed, says Langret, “visibility is an invitation to take a seat at the table; it is a form of progress. But co-hosting the party would be more appropriate. The urgency is in how to integrate diversity structurally.” One way is mentorship. “Current leaders should be actively cultivating their successors,” says Courtney J Martin, director of Yale Centre for British Art in Connecticut. “If you are a curator or a director, you should be identifying those in the field who might succeed you. Further, you should be talking to them about your pathways to success. If every art museum director in America did this with a plurality of people, the field would organically change. If not, it will remain stagnant.”

Wanting to make a change isn’t the same as actually doing it. Board meetings and declarative statements aren’t “doing it”. Across the pond, artists have taken it into their own hands: last year, Kehinde Wiley launched the Black Rock Senegal residency to offer artists of colour space to develop. In the UK, the Institute of International Visual Arts (Iniva) initiative Future Collect enables commissions by an artist of colour to be made for a museum. A signifier of real action from the commercial sector is the ongoing grant scheme set up by Carl Kostyál Gallery in London for black arts students in the UK and the US, while Creative Debuts have also launched a monthly grant for black British artists of all ages. Real change requires cheque books.

Galleries and museums do not operate in a vacuum; they must engage widely. Sepake Angiama, artistic director of Iniva in London, agrees. “The personal is political,” she says. “If we see our institutions as civic spaces, then we need these spaces to contribute to the conversations and dialogues around what it means to be human. You can’t separate politics from this. Sometimes, maybe, we need to go out not with the answers, but with the questions.”

Questions? Of those I have many. The main one is: what now? The conversations we are having with ourselves and with others should catalyse change. Art leads to empathy – and empathy leads to justice. I urge us to be aware of the role we have to play in standing up to racial bias. Art can help us understand our own subjectivity and transport us to other worlds, histories and viewpoints to better understand the world we live in now. I have faith in the power of a diverse, decolonised art world, and I have faith in the power of art. Let’s do better and be better. Together.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments