Does the Barbican’s Masculinities exhibition have important things to say about men?

For once, it’s the normative male who gets poked and prodded as a curiosity in this female-curated photography exhibition, and it may provoke bullish defensiveness among some. It forces Mark Hudson to look at himself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s a particular smell and feel that come with the notion of “masculinity”. We’ve all had a whiff of it, whether for a few moments or for half a lifetime and more: in the pub, at the football match, in the workplace or at school. The scent of testosterone in ill-washed sports kits, the hooting camaraderie, the emotional cramping that comes with “men without women” – even when women are physically close at hand. Not to mention the sense of dread you’ll feel later in life, getting stuck talking to an old school “man’s man”, who’s perfectly nice but whose cultural horizons don’t extend much beyond golf and Rod Stewart – or football and Oasis (the period changes but the feel is the same).

You might assume that the Barbican’s Masculinities: Liberation through Photography exhibition wouldn’t have much space for that kind of unreconstructed, lumpen maleness. Looking at the ways in which masculinity is “performed, coded and socially constructed”, and touching on “themes of patriarchy, power, queer identity, race, sexuality”, it sounds on paper like the kind of earnest exercise in wokeness that will focus on “alternative” forms of masculinity, myriad in our supposedly “polysexual” era, with the “heteronormative”, or even just the plain old heterosexual male, consigned to a shameful corner.

In fact, while there are a few gender-fluid figures here, they’re vastly outnumbered by manifestations of “traditional masculinity” – defined as “idealised, dominant (and) heterosexual”. Lebanese militiamen (in Fouad Elkoury’s perky full-length portraits from 1980), US marines (in Wolfgang Tillmans’ epic montage Soldiers – The Nineties), Taliban fighters, SS generals, Israel Defence Force grunts, footballers, cowboys and bullfighters fairly spring out of the walls from every direction. And what’s evident from the outset isn’t so much their diversity, as a unifying demeanour: a threatening intentness that comes wherever men are asked to perform their masculinity, but also a childlike vulnerability. Never mind that many of these embodiments of “dominant heterosexuality” will inevitably be gay, that many figures from the notionally white male American establishment – from cowboys to politicians – are actually people of colour, they’re united by a factor far more powerful and profound than perceived differences of ethnicity, ideology or sexual orientation: they’re all, for want of a better word, men. Imagine if these people sunk their differences and got together: they could rule the world. Oh sorry, yes, they already do.

This is a view of the male condition put together by women (the Barbican’s Alona Pardo and her colleagues). For once it’s the normative male – the ordinary geezer – who’s being treated as the “other”, to be prodded and poked as a curiosity by everybody else. And while the typical middle-class “liberal intellectual” Barbican-goer isn’t the ordinary geezer – if the “ordinary geezer” even exists – the effect is to make you identify with manifestations of masculinity that would otherwise feel profoundly alien.

As an absolutely typical member of that demographic, I have never got into Arnold Schwarzenegger-level bodybuilding, climbed into a communal bath after a rugby match or been in the Territorial Army (as seen in Peter Marlow’s images of British working class life). I would never – even at the time – have donned the shapeless flares sported by the shaggy-haired herberts in the urinal in Marlow’s image from a 1979 beer festival. And I’d certainly never attempt to do with my testicles whatever it is the American students are doing to theirs in Andrew Moisey’s pictures of Fraternity House rituals. Yet seeing these images in this context, I felt weirdly implicated. My instinct was to wheel defensively round to see who was looking, as though the female curatorial gaze was somehow drawing me into the same frame.

Masculinity, the viewer is made to feel, criminalises men (Mikhael Subotsky’s images of South African gangsters on morgue slabs); isolates them (Larry Sultan’s poignant image of his elderly father practising his golf swing in his sitting room); renders them stupid (Richard Billingham’s excruciating, but now classic photo essay on his alcoholic father, Ray’s a Laugh). To be a man, it seems, is to be condemned to endlessly act out archetypal “masculine” behaviour, whether you’re an elderly drunk in a Birmingham high-rise or the elite American students taking part in the shouting competition staged by Irish photographer Richard Mosse.

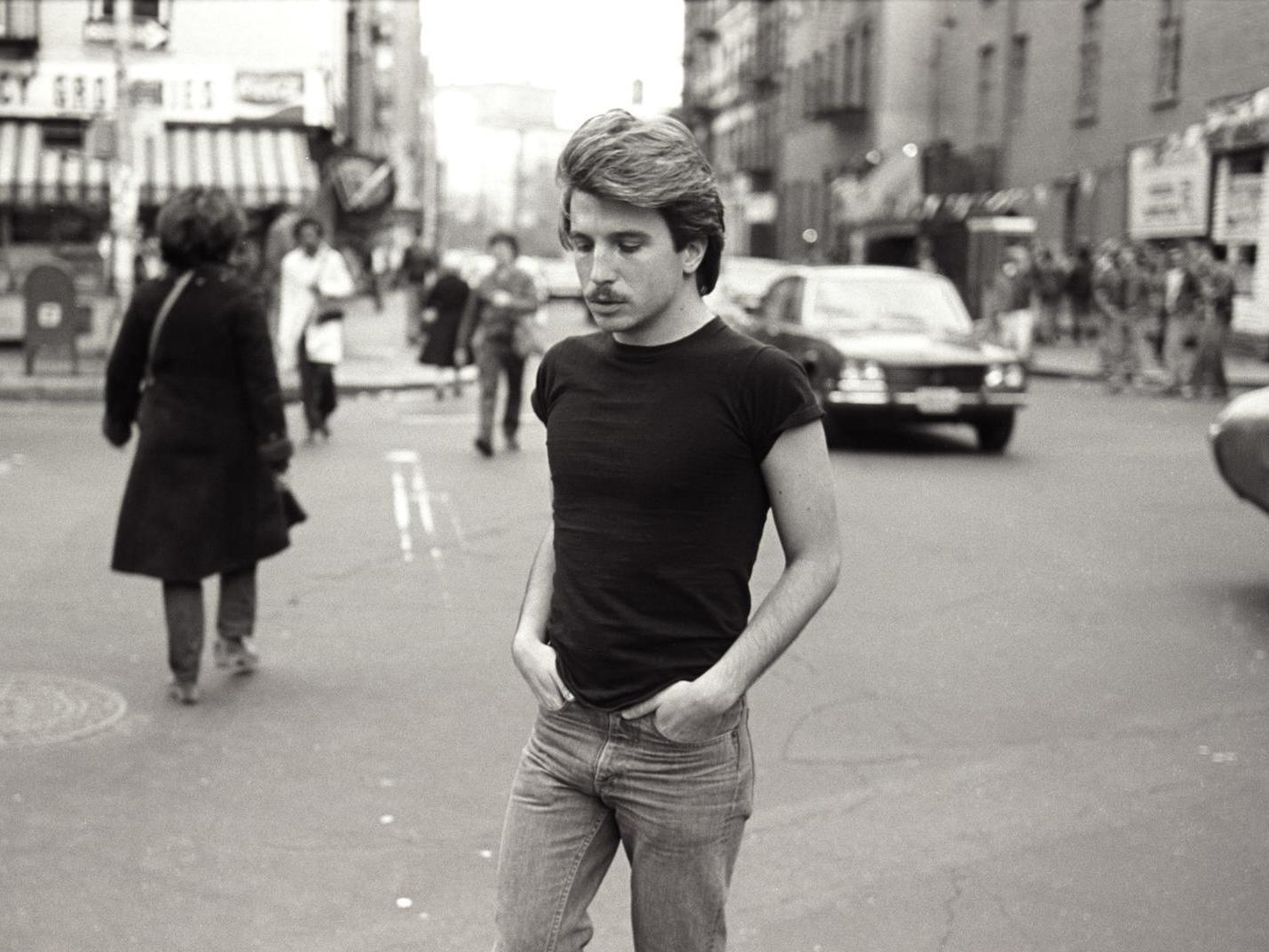

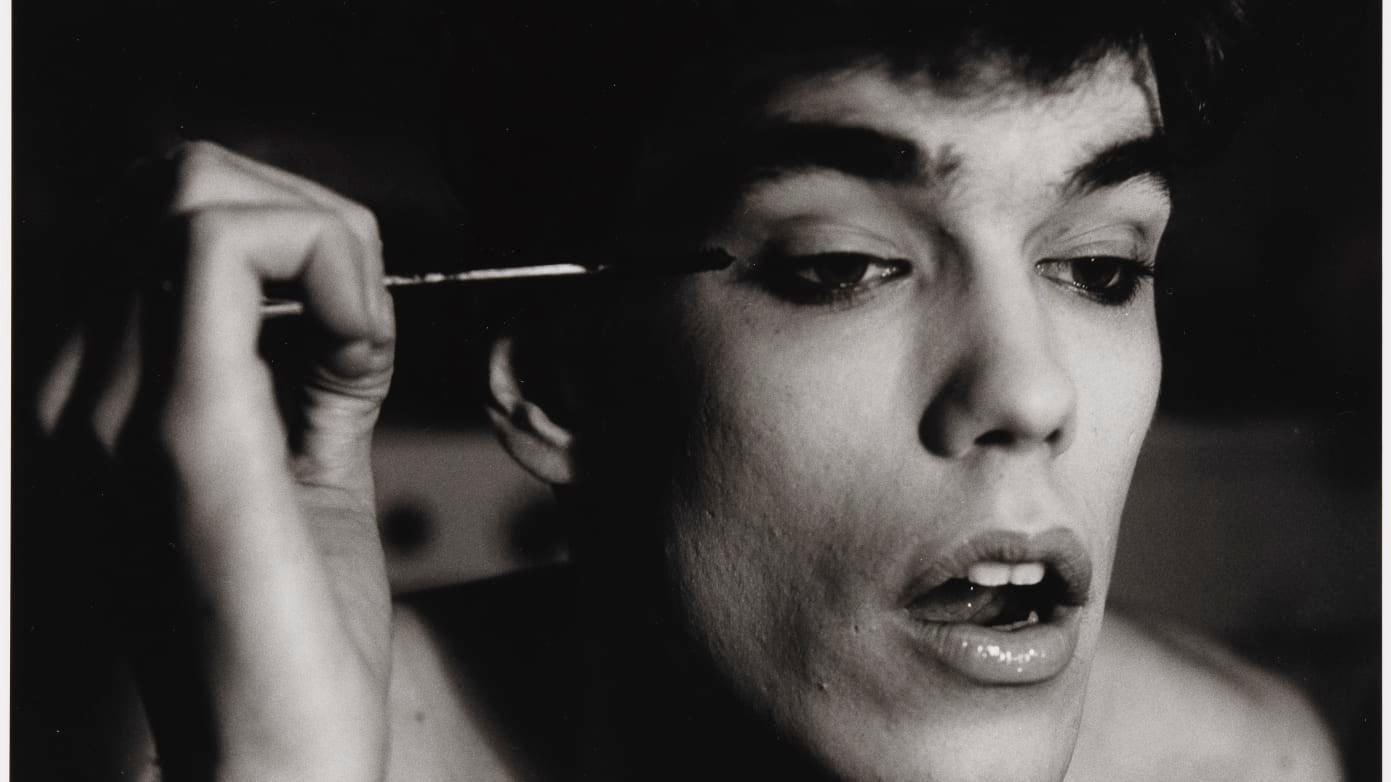

It’s enough to make you want to run away to Seventies New York, from where Peter Hujar’s portraits of drag performer David Brintzenhofe and images of young hustlers hanging around the Christopher Street Pier bring refreshingly diverse images of masculinity from the era. Yet if you look at Hal Fischer’s “Gay Semiotics” series, it seems gay men take even greater delight in acting out macho stereotypes – the Cowboy, the Leather Man et al – even than straight men. “Dominant” masculinity isn’t, judging by this exhibition, about sexual orientation, race, culture or even economic power, it’s just y’know, men.

By the time I got to Hank Willis Thomas’s hilarious Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, a coolly sardonic response to the use of iconic African-American imagery in advertising, I was putting myself in the position of the notional voiceless minority to the extent of wanting to shout at all those clever woke-people with their opinions on masculinity – smart-arse photographers, exhibition curators, feminist theorists – “Will you please stop telling me who I am!”

But that actually would be to miss the point. The whole #MeToo moment has made many men – particularly older, straight, white men – feel bullishly defensive. And if you fall into that category, it’s easy to feel like one of the left-behinders in the newly revived gender wars. But can’t that position be turned around? Shouldn’t the opportunity for a little self-reflection and increased self-knowledge, with a few shocking insights along the way, be welcomed?

For me, the work that felt most uncomfortably close to home – and the funniest – was the last: Hans Eijkelboom’s The Ideal Man, 1978, in which the Dutch photographer asked 100 women to describe their ideal man, then set about photographing himself in these aspirational personas. I was wondering when and if the urban intellectual – the type that corresponds most closely to the average London gallery-goer – would make an appearance. Here we see Eijkelboom carefully costumed and made-up in a range of variants on the Seventies “New Man”, the sensitive individualist, who wants to meet the needs of the liberated woman. The result is an array of slightly creepy post-hippies – scarves, tie-dye T-shirts, cowboy boots and all – whose sympathies with the women’s movement will, you feel, be entirely self-interested.

Go and see this highly entertaining exhibition, particularly if you’re a twitchy, self-regarding male of whatever gender or ethnic orientation. The worst that can happen is that you may be forced to laugh at yourself.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is at the Barbican, London, until 17 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments