Atena Farghadani: Iranian cartoonist opens up about her captivity

In her first interview to Western media since winning her release, Atena Farghadani talks about the horrific conditions behind bars in Iran and how she plans to continue producing political art, even if that means going to prison again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of the thousands of artists I have interviewed over the years, few have been as demonstrably brave as Atena Farghadani.

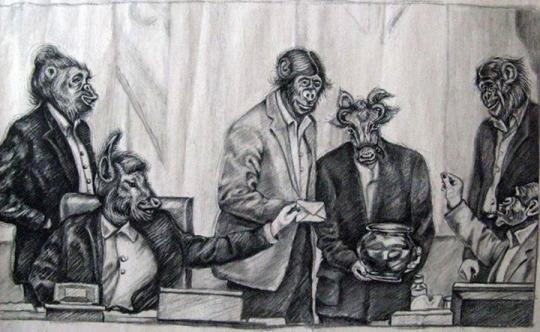

Farghadani was already an experienced activist in her 20s when she drew a cartoon mocking Iran's parliament to protest her native nation's anti-birth control policies. She was arrested by the Revolutionary Guard, a branch of Iran’s armed forces, in the summer of 2014 – her freedom taken from her.

When Farghadani was kept in jail for most of the rest of that year, she still would not be refused her art, as she flattened the disposable cups in her cell as makeshift canvas – until her materials were taken from her.

Early in 2015, a freed Farghadani spoke out about prisoner conditions, and was arrested again. By June, the 29-year-old woman was sentenced to nearly 13 years in prison – her immediate hope for even a shred of justice taken from her.

Soon, Farghadani shook hands with her male attorney, Mohammad Moghimi, who was likewise jailed for a time as a result. In response, Farghadani's captors subjected her to a virginity test – apparently in an unsuccessful attempt to take her dignity, too.

Two months ago, Farghadani was finally freed.

Today, Farghadani vows to continue to make political art from within Iran, where her voice may have the greatest effect.

This is a Q&A with the artist, in her first interview with the Western press since winning her release. The interview was conducted via email through Nikahang Kowsar, the Iranian-born board member of the Washington-based Cartoonists Rights Network International, who himself was jailed in Iran in 2000 for his art.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Michael Cavna: First off, Ms Farghadani, let me just say, now that the opportunity finally provides: congratulations on your freedom. We heard reports about the difficult conditions while you were imprisoned. How are you feeling, and doing? And how does one even recover from a mental and physical ordeal such as yours?

Atena Farghadani: I appreciate all the efforts you and your colleagues have made so far. My feelings at the moment are not very pleasant, because it's like I'm stuck in a limbo. Obviously, the mental weariness of imprisonment is more serious than the physical problems caused by it. At the moment, since I've arrived at the certainty that there is miracle lying in the art of drawing and painting, I'm more determined to continue doing it than ever.

MC: You, of course, have become an inspiration to so many around the world, Atena – a beacon of creative and political resistance. While you were in prison – in Evin and elsewhere – how aware were of you of the degree to which the outside world knew and was following your story? Was Mr Moghimi able to provide you with news in that regard during your case?

AF: When I was in prison, I wasn't aware of outside events and the news about me, especially in 2015, when I was on a hunger strike in the gruesome Gharchak prison. At that point, I was absolutely hopeless and thought I would die there, without my voice ever being heard. But I kept going with the strike, constantly thinking that even if I die, I have a clear conscience for I've died for my beliefs and goals. After my appeal to be transferred to Evin prison was approved and I ended my hunger strike, my attorney, Mr Moghimi, gave me all news in two very short visits, boosting my morale and giving me hope.

MC: For the Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian who was in an Iranian prison for more than a year, one aspect of the ordeal of being there, for him, was not knowing one's fate – feeling as though you are in the legal hands of a system that might not practice justice as you, the prisoner, might understand it, and all the uncertainty. Could you talk about what was hardest for you about your long detentions and imprisonment – and whether you thought you might actually spend more than 13 years behind bars for your outspokenness and artwork?

AF: When I heard my sentence of 12 years and nine months' imprisonment, I thought it was unbelievable and very unjust. Since I was 29 at the time, I calculated that I'd have to be in prison till I'm 42. At first, I had a hard time accepting the sentence, but then I thought I could use this time, as much as possible, to draw and have an opportunity to put an exhibition of my works after my release. I considered prison my home for the next 13 years. My family could not accept this new attitude of mine towards prison and my beliefs and at times they were frightened by it and wept. At these times, I had no choice but to make faces for them from behind the glasses in the visitation cabin to make them laugh. These were the hardest and most bitter days I had during my incarceration.

MC: Why do you think you were ultimately awarded your freedom? What swayed the legal system?

AF: As the results of the efforts made by my family and my attorney, and pressures from the international community and human rights organisations, my sentence was reduced from 12 years and nine months to 18 months and a three-year suspended sentence for insulting the supreme leader of Iran. I am grateful to all those whom I don't know and to whom I owe my freedom.

MC: Is there anything about your case (including the reported “virginity test” after shaking your male attorney's hand) that we should know about?

AF: Yes, that's ... caused lots of confusion: considering the fact that my family had refuted that I was tested for virginity and pregnancy because of shaking hands with my lawyer, people wanted to know the truth. The truth is that my family was in denial at the time because of the dominant traditions and the Iranian culture and fear for more pressure from the judiciary on me. But the tests were actually made, which led to my three-day dry hunger strike in objection. The Islamic Republic of Iran later confirmed this event. It is noteworthy that both my attorney and I were exonerated from the adultery accusations and I owe this to the judge of this specific case, who issued our exoneration verdict independently and neutrally in spite of the sensitivity of the case and security pressures.

MC: What art are you making now – and will your art remain political, or might you steer your art and activism in a different direction?

AF: Right now, I'm painting and making a collection of artwork with political and social contents, and I intend to have an exhibition within a year, but I'm afraid I can't hold this exhibition in Iran, and thus I'm even thinking of having a street gallery, though it wouldn't be without consequences. I believe that “criticism” serves art. So, I have decided to use my art to challenge social issues as I have done before, like the cartoon I drew after I was released as an objection to the dean of Al-Zahra University, who expelled me and many other students.

MC: Do you feel safe now in Iran, and can you imagine coming to visit America?

AF: Of course, I could be more successful in developed countries, but when I witness the problems Iranians are dealing with, such as economic and cultural poverty and various limitations, I cannot leave them alone to live in another country in a better situation, despite all the constraints and issues I would possibly face. Many Iranians, though, have had to leave their homeland because of these constraints and have been active outside their country to improve human rights in Iran and are successful, too. But I don't see it in me to be able to leave my country because of my emotional attachments, which is perhaps a weakness of mine, but as long as I live, I will stay here, even if I have to go to prison again.

MC: Are you comfortable with being a symbol for artistic resistance and political freedom of expression?

AF: I don't consider myself a symbol. I simply acted on my thought, beliefs and principles, and I think all people have an individual and social task to fulfil.

MC: Is there something I didn't ask that you would especially like to tell readers?

AF: Yes, one of the things that has had (a) destructive impact on me after my release was the incarceration in the gruesome Gharchak prison, which is for prisoners with all sorts of non-security crimes. What bothered me the most was to see inmates – many of whom were victims of the economic and cultural poverty in the Iranian system – who were not treated like human beings; their most basic rights were violated. I consider Gharchak prison as a graveyard of time ... where time dies. I sometimes see those inmates in my nightmares. Once, I saw one of them collecting and braiding my fallen hair.

I see myself as a reflection of other people, and to respond to this question of yours, I would like to reflect the wishes of other women imprisoned in Gharchak – most of them longed for cool drinking water, instead of the salty lukewarm water they had to drink from the tap. There were only four showers in each chamber for 189 inmates, with the same salty water for only an hour a day, so many of them missed a hot shower. Many of them (condemned to) death sentences wished to plant something that wouldn't wither from the salty water and (to) see that plant – to leave a living mark before departing from this life.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments