‘These are the traces of this tumult’: The precious artworks looted by the Nazis

A new exhibition on at the Jewish Museum in New York brings together over 150 artworks and artefacts, from paintings to Torah scrolls, that were seized by Nazis. Nadja Sayed speaks to its curators

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1940, Jewish art dealer Paul Rosenberg fled Nazi-occupied Paris for America. Before he departed, he stored his most valuable paintings in a bank vault in Libourne, France.

His art collection, which included Henri Matisse paintings, was seized by the Nazis. They took the paintings and stored them at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, a Nazi storage depot. Then, they broke into Rosenberg’s Paris art gallery and turned it into the Study of the Jewish Question – only to host anti-Semitic exhibitions.

The artworks were finally returned to Rosenberg’s heirs in 2015. But this is just one example of how the artworks were stolen and traveled through Nazi-occupied Europe before being recovered by collectors and historians both during and after the war.

Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art, a new exhibition opening on 20 August at The Jewish Museum in New York City, tells some of these stories. Over 150 artworks and ceremonial objects are on view until 9 January 2022, showcasing modern art, photographs and Judaica that was looted during the Second World War.

The Jewish Museum in New York was used as a depot, as part of a recovery effort. “Art can tell these stories,” says Darsie Alexander, who co-curated the exhibition with Sam Sackeroff.

“When you look at a work of art, you can’t always see what it has been through,” she adds. “It has traveled through chapters of history. We’re showing works that haven’t been seen together in many years.”

The Jewish Museum’s collection today includes over 200 pieces of these recovered artworks and ceremonial objects; the Jewish Museum in New York was used as a depot, as part of a recovery effort. It’s a historic moment for the museum. “This is the first time we are shining a light on that remarkable period in the postwar story of art,” says Sackeroff.

Thousands of artworks were looted during the Second World War. They traveled through distribution centres before being recovered by collectors after the war. It is a miracle many of the works survived. Over a million artworks and over 2 million books were recovered postwar, while even more were apparently destroyed by the Nazis.

The exhibition includes paintings by 20th-century modern masters like Marc Chagall and Paul Cezanne, as well as rare photographs and documents that trace the artworks through the 1940s and 1950s.

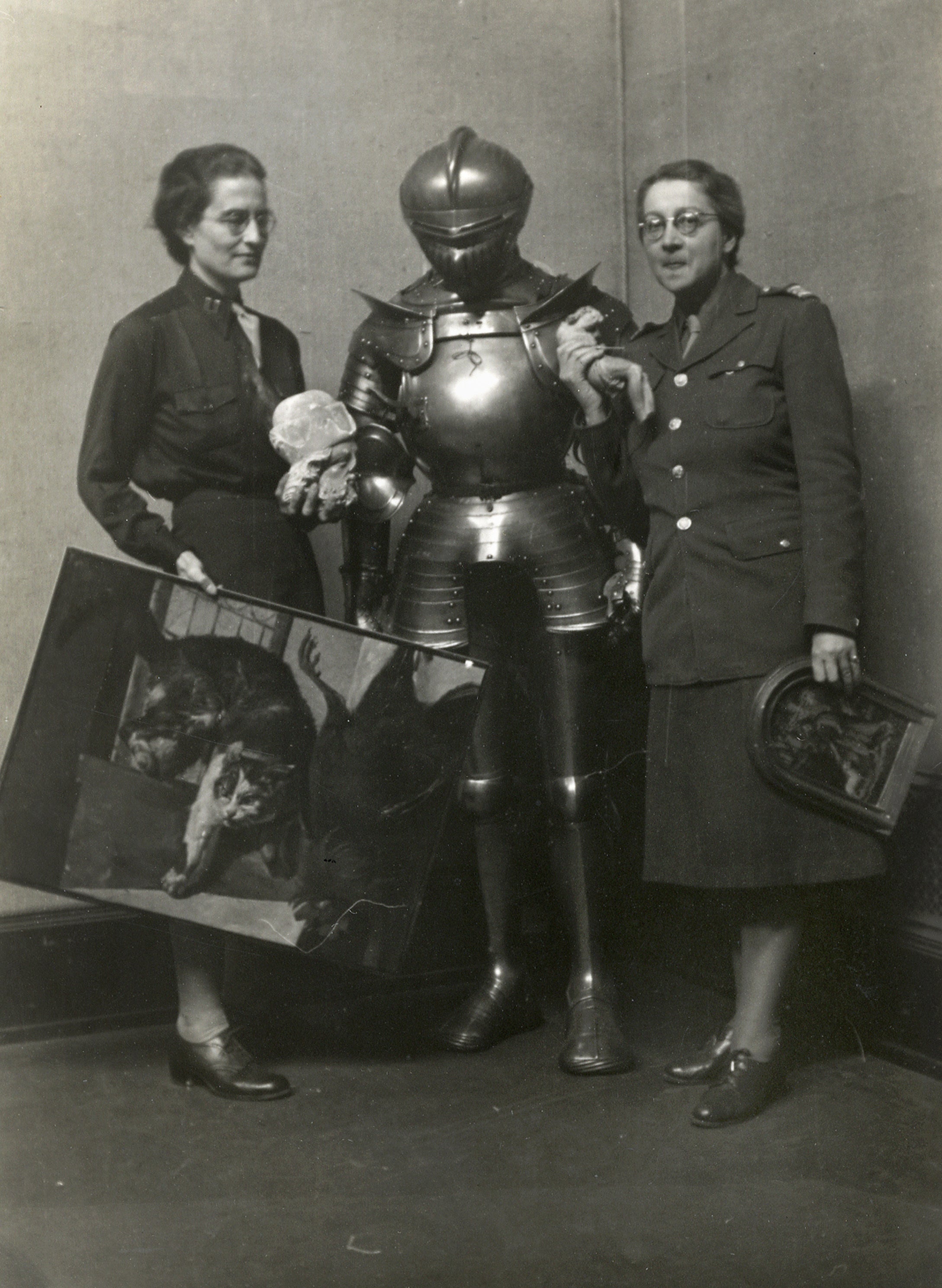

This exhibition is also drawing attention to something often overlooked: the “many women part of this effort, many behind the scenes”, says Alexander. “We draw attention to the people who helped recover these works, as efforts are less visible in the popular imagination. We wanted to bring their names forward.”

Photos of art historians like Rose Valland and Edith Stanton are on view, while other instrumental people include librarian Edgar Breitenbach and US Army General Lucius Dubignon Clay, both of whom aided in art recovery efforts, among others.

The art and objects were taken from synagogues and put into Nazi research libraries. “A lot of works were destroyed, while some objects were melted down for the silver,” says Sackeroff. “A fraction did survive and were recently found in Nazi bunkers. These artworks are the traces of this tumult.”

Even now, Germany struggles with the restitution of artworks that were seized during the Second World War. Germany recently returned a painting by Erich Heckel to the heirs of its Jewish owner. Over 1,400 Nazi looted artworks were uncovered in 2012, as well, which was referred to as the Munich Art Hoard.

The condition of each artwork tells their story. “They’re scratched, damaged, bent and missing pieces,” says Sackeroff. “They communicate how unlikely it was they did survive this destructive period. We take visitors on a tour through these pieces.”

There are rare black-and-white photos from 1942 depicting piles of books looted by the Nazis, as well as objects like an Italian Torah crown from 1698, a prayer book from Poland dated 1837 and an 18th-century silver amulet from Venice.

There is a selection of prayer books, some leather-clad with handwritten ink on paper, others with ornate silver covers. There are Hanukkah lamps, a pewter pitcher and a number of Passover cups from the late 18th century.

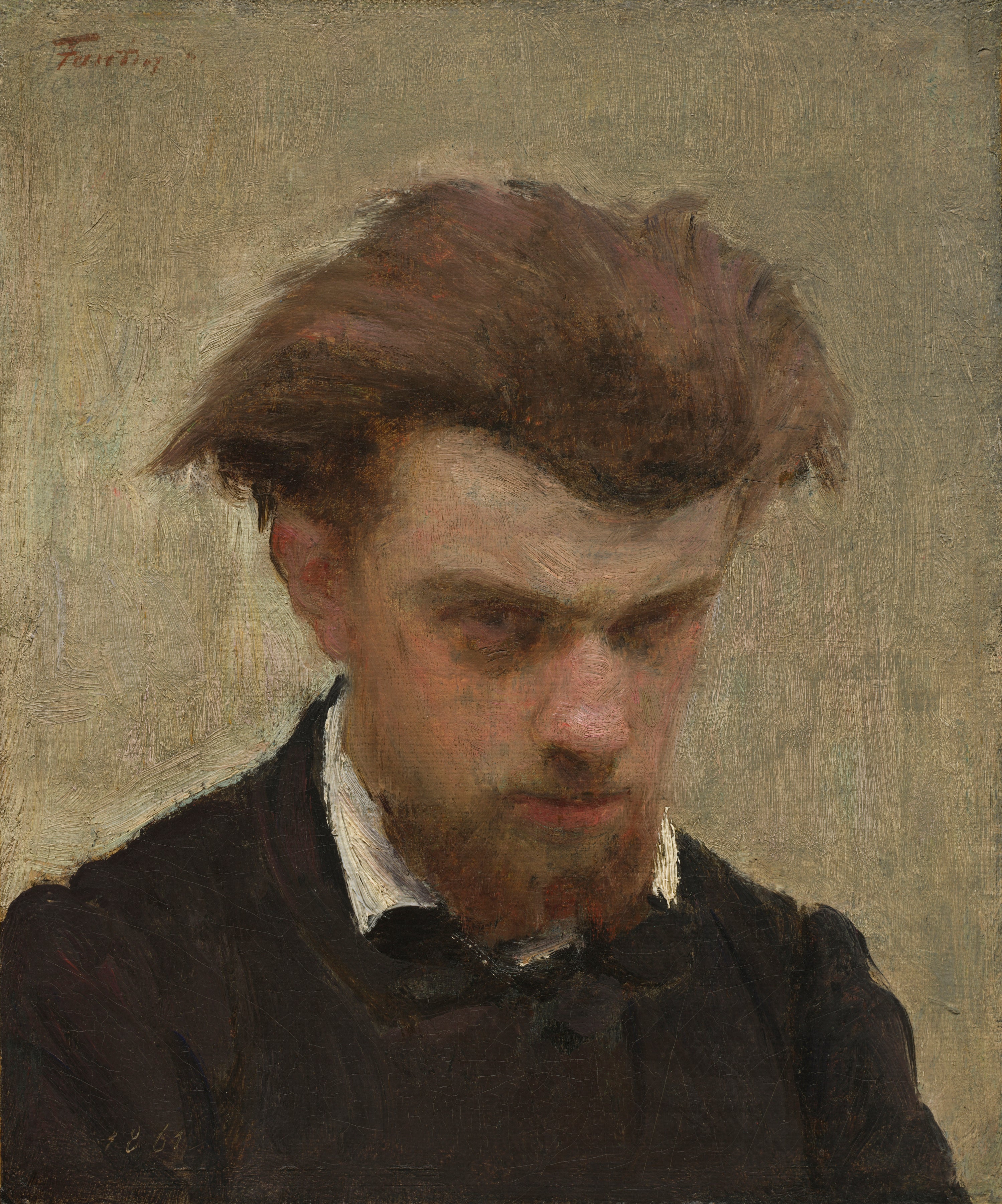

“The collection has a number of artworks by modern masters, which belonged to gallerists in Paris,” says Alexander. Among the French paintings on view, they include a self-portrait from 1861 by Henri Fantin-Latour and works by Camille Pissarro and Gustave Courbet.

Paul Klee’s painting Two Trees, from 1940, is also on view, as is Marc Chagall’s Purim from 1916 and Paul Cezanne’s Bather and Rocks from 1860. Henri Matisse’s 1939 painting Daisies, once owned by Rosenberg, is there too.

The photographs on view tell the untold story of the Jewish intellectuals who fled Europe. A number of photos by German portrait photographer August Sander are on view, which were a part of his 1938 series The Persecuted, depicting seated portraits of persecuted Jewish men and women.

He photographed his Jewish friends and colleagues who wanted to leave Germany while the Nazis seized power in the late 1930s. While Sander wasn’t Jewish himself, he was an anti-fascist. The photos are part of his larger series, People of the Twentieth Century.

There are also photos by German photographer Johannes Felbermeyer, who was the chief photographer at the Central Collecting Point in Munich from 1945 to 1949. He photographed the process of repatriation of artworks after World War II, including 500 paintings and sculptures from Austria, Belgium, France and Italy, among other European countries.

In 1947, the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Inc. was founded to document salvaged works of looted art in postwar Europe, helping find homes for over 360,000 books, Torah scrolls and ceremonial objects.

“It was co-founded by the US government to recover and redistribute Judaica that had belonged to communities destroyed during war,” says Sackeroff. “They were heirless or orphaned objects where it wasn’t clear who to return them to. They acted on behalf of the Jewish people.”

One of the main figures honoured by this exhibition is Rose Valland, a French art historian who was working at the Jeu de Paume in Paris when the Nazis took over. They kept her on staff. “She took photos of Nazi documents, which helped locate the objects much later on,” says Alexander. “How things survived was sometimes luck. She was a celebrated historian who worked behind the scenes.”

One photo in the exhibition from 1945 or 1946 shows Velland alongside museum official Edith Standen at a Central Collecting Point in Wiesbaden, Germany. They pose alongside recovered paintings while standing beside a knight in armour. “These women were at the head of the recovery effort,” says Sackeroff. “They went through this huge mass quantity of cultural material that was stolen and uprooted by Nazis.”

“They tried to return objects to their rightful owners,” he adds. “In doing so, they set the precedent we have today that cultural plunder is not appropriate. They insisted that everything be returned to their rightful owners. We’re seeing them here in a moment of bravery and principle.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments