Artist Norman Cornish resented being lumped together with the other Pitman Painters

Until his death last week at the age of 94, Cornish was known as the last living Pitman Painter - a man who transcended the hardships of working life to become an artist, without ever compromising his roots

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

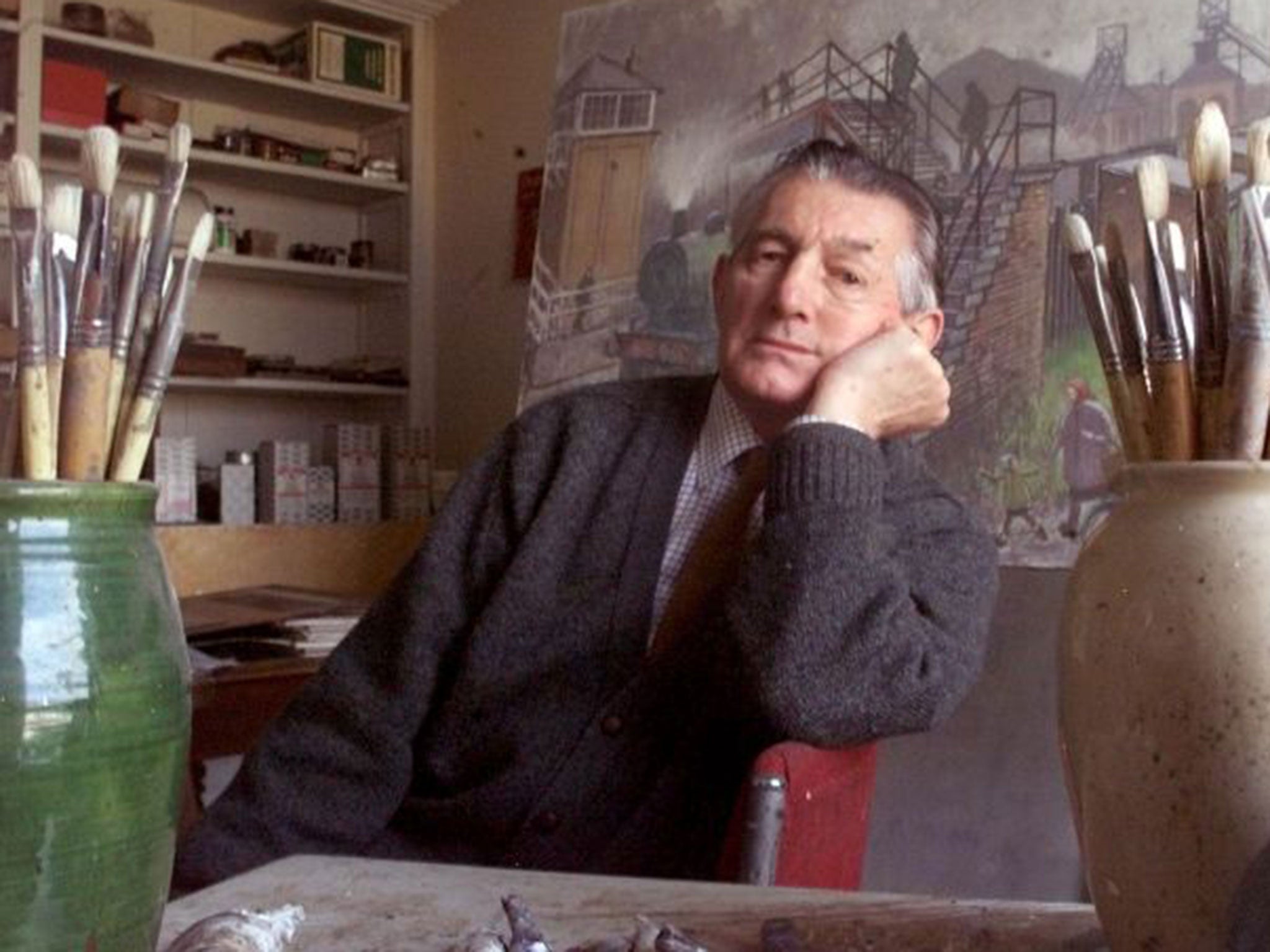

Your support makes all the difference.If the spirit of a place can be captured (or possibly created) through visual art, then Norman Cornish achieved this symbiotic feat in his relationship with Spennymoor, the County Durham town where he lived all his life. Until his death last week at the age of 94, Cornish was known as the last living Pitman Painter, but it's a title he might not have appreciated.

He was both a pitman and a painter, but he lived and worked nearly 50 miles away from the miners in Ashington, Northumberland, who signed up for Art Appreciation classes at their local YMCA in 1934.

Like the Pitman Painters, Cornish was a man who transcended the hardships of working life to become an artist, without ever compromising his roots. Indeed, his roots were his art, the panorama of terraced houses, nicotine-tinted pubs and well-worn paths to and from the pit, where the looming network of cables and gantries was the prelude to contortions of confined spaces defined by a lining of props and rails.

This working environment hardly held the promise of personal development, especially when the 14-year-old Cornish signed up at Dean and Chapter pit, so notorious for its high injury rate that it was nicknamed the Butcher's Shop. The eldest of nine children, Cornish was already a keen artist when his father lost his job, and had no choice but to go and work down the mines, sketching in his spare time.

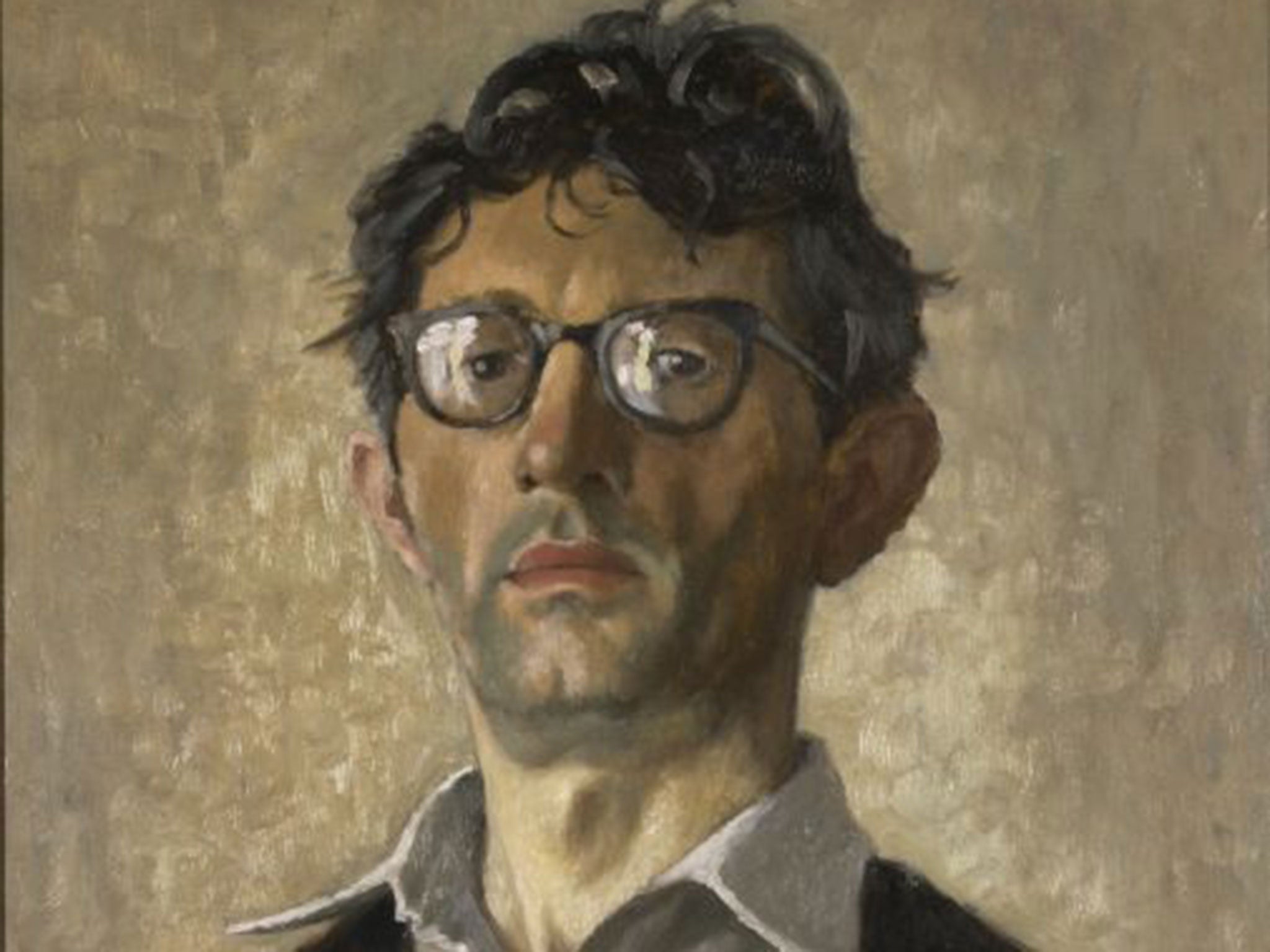

In Ashington, the off-duty miners honing their aesthetic sensibilities on slides of Michelangelo's work risked ridicule, but their tutor, practising artist Robert Lyon, quickly set the group to producing their own paintings of everyday life. Though the intention was not to create finished works of enduring value, the enterprise caught the mood of the time, when intellectuals such as the Mass Observation group set out to create "an anthropology of ourselves", while the Modernist art establishment looked for something fresh in the work of "naïve" and "primitive" artists.

But The Ashington Group fell out of favour and it wasn't until the art critic William Feaver rediscovered their work in the 1970s, and coined the term "The Pitman Painters", that they reached international acclaim. In 1980, their permanent collection became the first Western exhibition in China after Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, partly because Chinese officials were taken with the idea of workers' art. Feaver's subsequent book inspired the acclaimed 2010 play The Pitmen Painters by Billy Elliot writer Lee Hall.

But there were other miners who painted, in Nottingham and Wales and, of course, Spennymoor. And while The Ashington Group were having lessons in lino-cutting with Lyon, Cornish was benefiting from the Spennymoor Settlement, a sociable experiment in informal community education that also fostered the talents of author Sid Chaplin and fellow miner/artist Tom McGuinness.

Their subject matter might have been similar – the hunched, flat-capped men, the whippets, the amber-toned bar scenes – but Cornish resented being lumped together with the other pitman painters. In 1970, he railed: "I'm sick of being looked at like some sort of zoo animal or specimen... out of the depths comes this bloke and paints his pictures. It assumes that a man who works in a mine is not up to writing or painting or playing music. But it simply isn't true."

He didn't much care for Hall's play either, telling one interviewer: "There were some bits that made me feel that it was a bit of an insult to these lads – because they were the best kind of working people who wanted to be educated. There was nothing silly about them."

Cornish's work in the mines lasted for 33 years, but once he found his stride as an artist, the pits were only one element of an interlocking world where wives gossiped and the green chip van punctuated the streets with clamour and colour.

His local identity is cherished with more pride than ever as the signposts of his world have all but vanished behind a bland anonymity. For Cornish, that world was held inside his head, and the paintings have become snapshots of a shared, shaped memory of which the pits were only a part.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments