The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

In today’s art auctions, the ‘male gaze’ is going out of fashion

The National Gallery in London paid about $4.8m for a work by a 17th century female artist, but pieces by male artists of the 19th century are out of fashion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Taste is changing. When private collectors and public museums acquire works of art, these acquisitions are being made in a very different cultural climate from that which prevailed in the late 20th century, let alone the late 19th.

The market for contemporary art is, for example, being transformed by some curators’ desire to rehabilitate underrepresented names, particularly female and African-American artists. Similar imperatives are driving museum purchases of pre-20th century works.

Earlier this month, the National Gallery announced that it had bought Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Self Portrait as St Catherine of Alexandria” for £3.6m.

Artemisia, though, is hardly an unknown talent. Hailed in her own lifetime as a “prodigy of painting, easier to envy than to imitate”, the most renowned female artist of the Italian Baroque was the subject of solo exhibitions in Milan in 2011 and Rome in 2016. Her extraordinary life story has become a set text of feminist art history.

In 1611, Artemisia, 17, was raped by Agostino Tassi, an artist collaborating with her painter father, Orazio Gentileschi. Tassi was subsequently charged and found guilty but only after his victim had been forced to endure testimony under thumbscrew torture and accusations of immorality. The condemned rapist never served his sentence of exile.

The self-portrait, painted in Florence around 1615-1618, shows the artist leaning against a wheel studded with iron spikes. “It’s tempting to read the painting biographically,” says Letizia Treves, the curator of Italian, Spanish and French 17th century paintings at the National Gallery.

“Artemisia had long been identified as an artist whose works are missing from our collection,” Treves adds. “She’s an artist we wanted to represent primarily for her artistic achievement, in addition to the fact that she is a celebrated female artist.” The acquisition brought the number of works by women among the 2,300 owned by the National Gallery to 21.

The transaction was a coup for London-based dealers Marco Voena and Fabrizio Moretti, who had bought the newly discovered painting in partnership in December at a Paris auction for €2.4m with fees (about £2.14m), an auction high for the artist.

“You have to think differently today,” Voena says. “The taste of the connoisseur is over.”

“You have to ask what the image you are buying means to people,” he adds. He says Artemisia’s self-portrait was “a picture of a heroine, the sort of image you see on Instagram”.

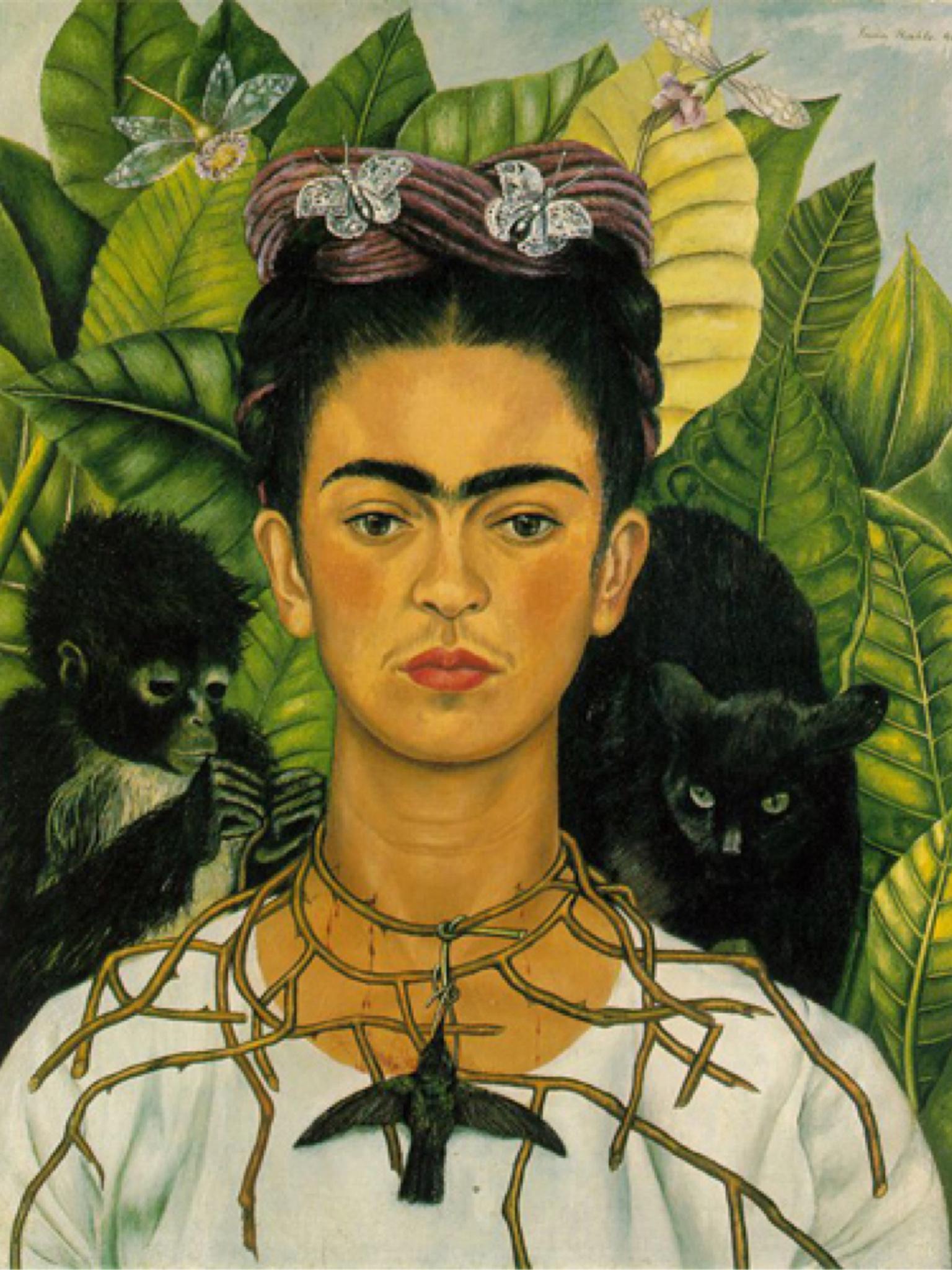

The popularity of exhibitions devoted to female artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo (whose Making Her Self Up show is drawing crowds at the Victoria and Albert Museum) are signs of our cultural times, according to Voena. “Museums want to sell tickets,” he says.

Visitors should, however, be able to view the Artemisia self-portrait without charge when it goes on display next year, after conservation. But with visitor numbers down 17 per cent last year, the National Gallery is aware of the need to show old art that appeals to new sensibilities.

If those sensibilities are making the market for old masters more selective than ever, where does that leave the academic painting and sculpture of the 19th century, the art produced when industrial Europe was exploiting its colonies and its visual culture was dominated by what college art history departments call the “male gaze”?

On Wednesday, Sotheby’s held a 120-lot auction of technically proficient 19th and early 20th century figurative sculpture. Teetering on the edge of kitsch, these white marble female nudes and bronzes of noble Africans have fallen out of fashion with western collectors. Fewer than 10 people turned up for the sale.

But the art market is a global business these days. Despite the near-deserted room, 70 per cent of the works found buyers, with most of the successful lots attracting telephone bids and bidding online.

The top price in the sale was the £334,000 given by a telephone bidder for Sylvie, a life-size marble statue of a slender female nude combining her long hair, by little-known French sculptor Prosper d’Épinay. The final price was far above the £180,000 high estimate. The second-highest bid came from a client based in Asia, Sotheby’s said.

“The Chinese are getting rich and they want to invest in western culture,” says Natalie Lo, a Chinese collector who was in the salesroom with her adviser. “There’s a lot of potential, and we want to anticipate it,” adds Lo, who bought, among several purchases, a circa 1920 marble bust of Beethoven by Italian sculptor Alfredo Pina for £10,000. Coming from a collecting culture inundated with fakes, Lo said the dependable authenticity of 19th and early 20th century European sculpture was “very important”.

But with interest from western collectors contracted, and Asian buying in its early stages, academic sculpture has become a niche market. Sotheby’s latest biannual sale of this material mustered a modest £1.9m, down 24 per cent on the equivalent auction last year.

“So much of this period of art is based on the male point of view. People have called it 19th century eroticism,” says Robert Bowman, a London dealer in sculpture, whose gallery is hosting a selling exhibition on the late-Victorian new sculpture movement. “There’s a sensitivity to political correctness, which is right, but sometimes it can go too far,” Bowman adds, referring to the squeamishness that today’s art world feels about certain subjects.

For many, it went too far in January, when the Manchester Art Gallery removed from public display John William Waterhouse’s 1896 pre-Raphaelite painting, Hylas and the Nymphs, showing a young warrior being lured into a pond by seven semi-submerged naked girls.

The removal, undertaken as a performance by artist Sonia Boyce, had been informed by the #MeToo campaign, according to Clare Gannaway, the museum’s curator of contemporary art.

After a backlash, the painting was put back on display in February.

“I do not believe this work is a significant or exceptional example of a (heteronormative) male colonialist gaze in this work, certainly less so than, for example, in Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Tim Barringer, professor of the history of art at Yale University, says in an email.

“I admire Sonia Boyce’s work but in this case she, and the curators at Manchester Art Gallery, in my view got it wrong,” Barringer adds.

Barringer might also have referenced Picasso’s 1905 painting of a naked teenage girl, “Fillette à la Corbeille Fleurie,” which drew just one bid – albeit of $115m – at Christie’s Rockefeller collection sale in May.

On Thursday, a 1900 Waterhouse painting in a not dissimilar vein came up for auction at Sotheby’s. The Siren, showing a shipwrecked sailor gazing up at a naked teenage girl, this time holding a strategically placed lyre, was being offered from the collection of New York music impresario Seymour Stein, estimated at £1m to £1.5m. It sold for £3.8m with fees.

“There may have been that fuss in Manchester, but it doesn’t worry the men and women who buy pre-Raphaelite pictures. It’s an elderly customer base,” says Rupert Maas, a London dealer who was in the salesroom.

Auction demand for Waterhouse might appear #MeToo-proof at the moment, but elsewhere, scrutiny of the male gaze is shaking up values – in every sense – in the art market.

Even Picasso had better watch out.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments