Why Andy Warhol still surprises, 30 years after his death

This week marked 30 years since Andy Warhol’s death, but the artist still manages to intrigue us from the grave, especially with his time capsules packed full of objects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

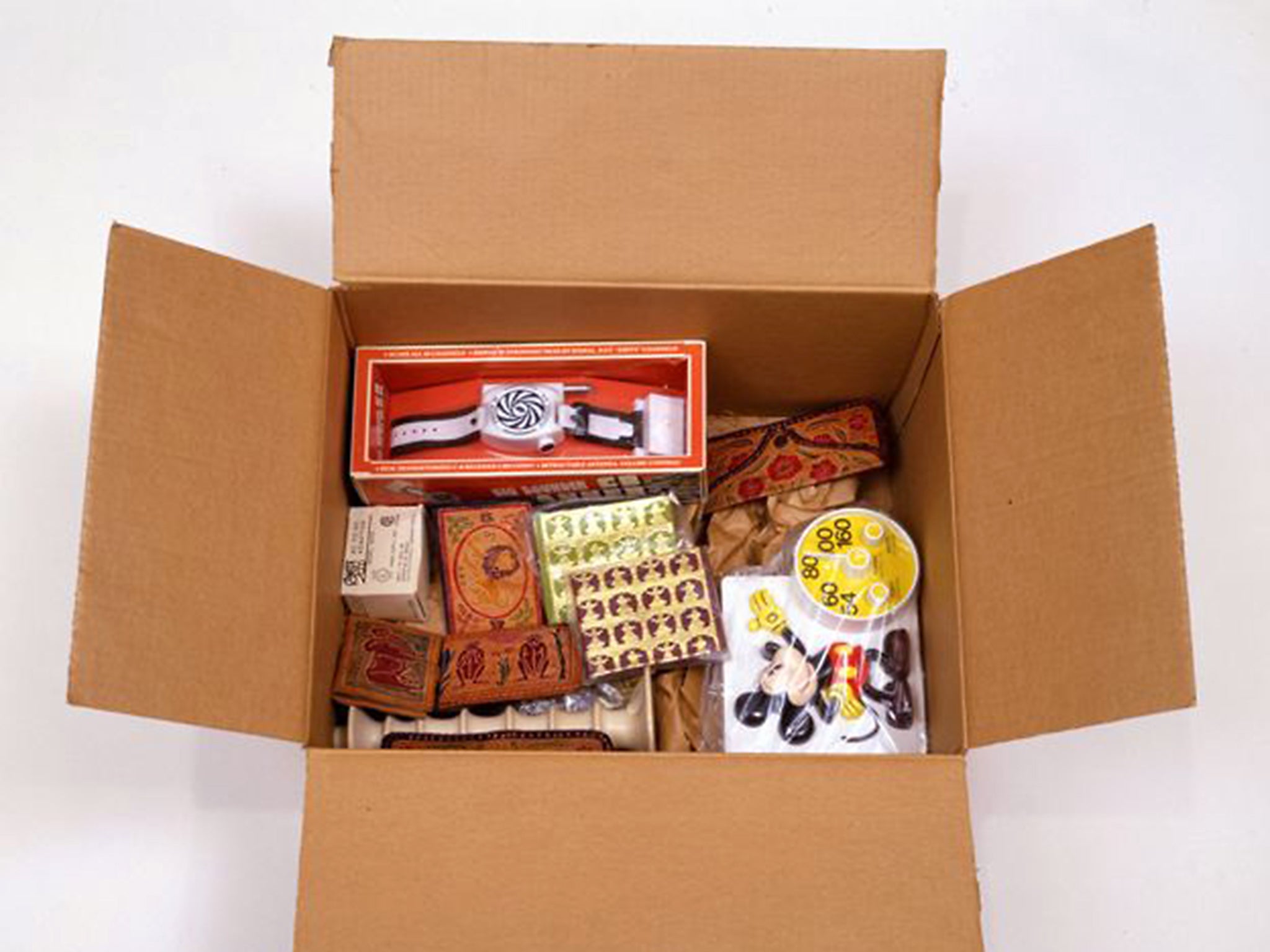

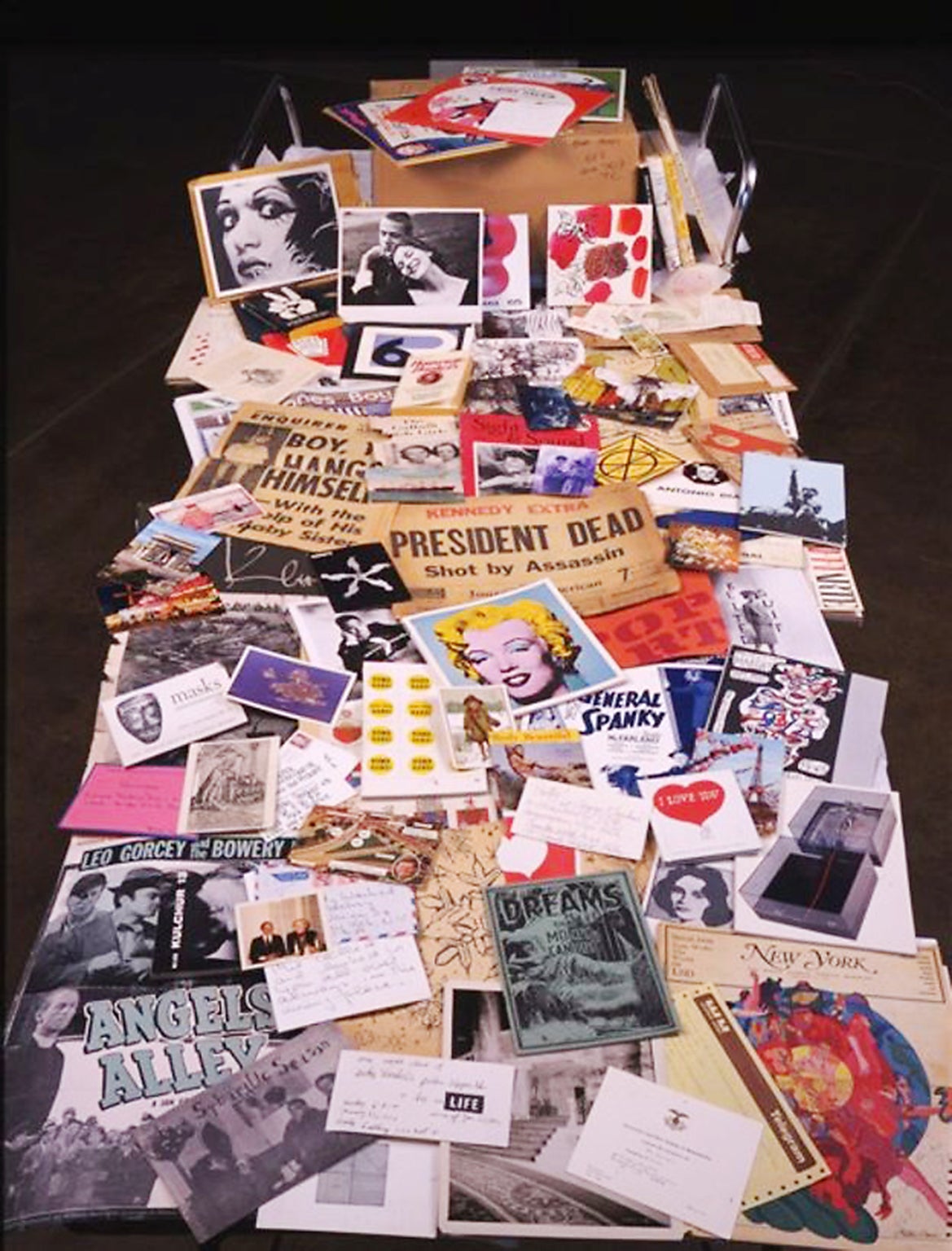

Your support makes all the difference.During the last 13 years of his life, Andy Warhol made 610 time capsules. The artist stuffed these parcels with found objects and everyday ephemera, before consigning them to storage.

When the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh started to carefully exhume and catalogue their contents, they discovered that the boxes contained everything from newspaper articles, junk mail and toenail clippings, through to source photographs for projects, letters for commissions, and even the occasional unsold artwork. The last intact time capsule was opened in 2014 by an anonymous bidder who paid $30,000 (£24,000) for the privilege. It seems safe to say that, 30 years on from his unexpected death at the age of 58 in 1987, Warhol’s work still has secrets to reveal.

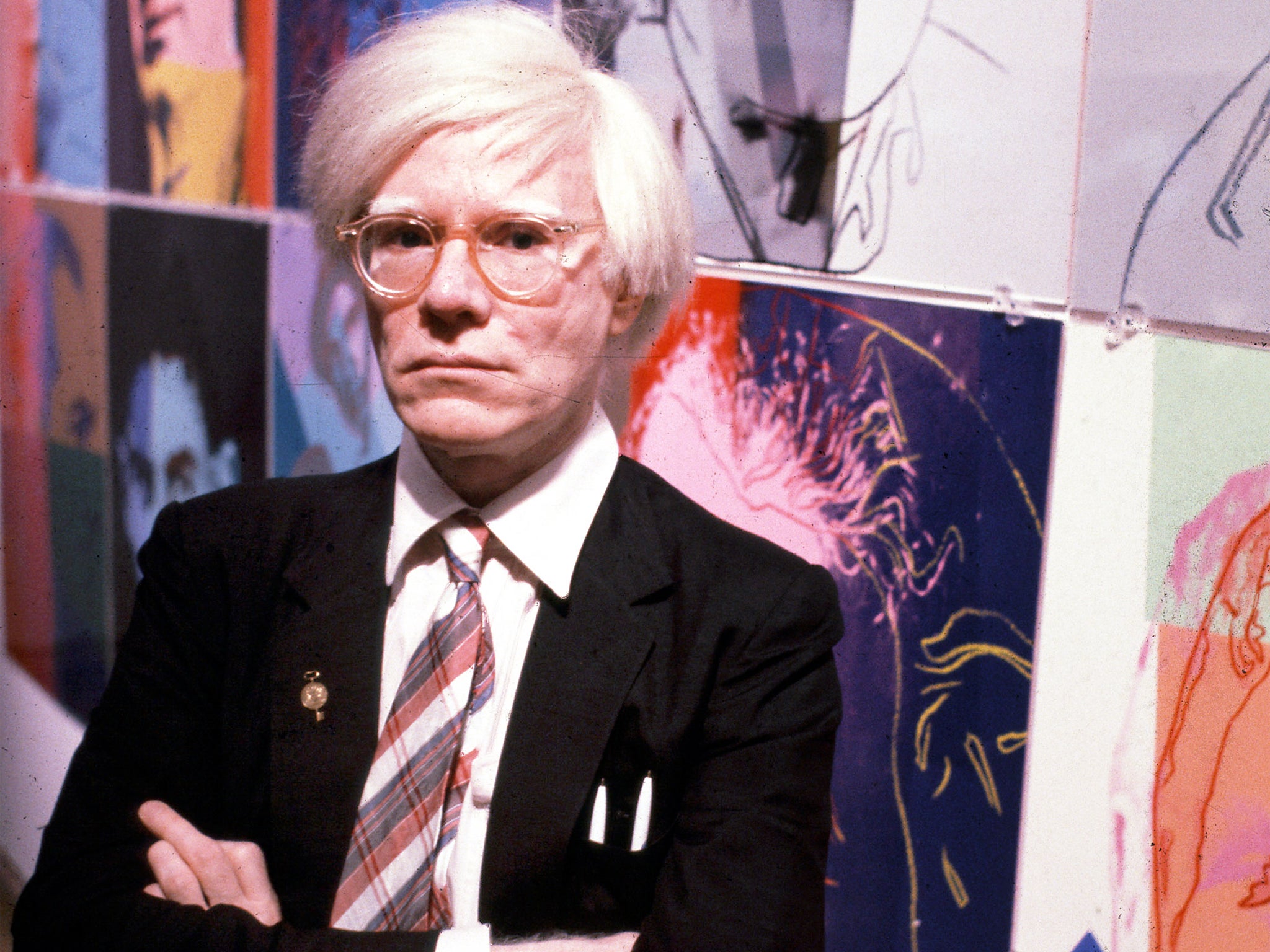

This is despite the fact that Warhol has become one of the most well known artists in the world, with endless books and essays devoted to him. His early paintings of the ubiquitous Campbell’s soup cans and iconic silkscreen images of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe are now instantly recognisable. Warhol currently enjoys an enviable combination of popular appeal, market success and critical recognition. His work is widely agreed to hold an important – and, if anything, growing – place in histories of post-1945 artistic production.

The latter status stems in particular from Warhol’s experimentation in avant-garde film, with works like Sleep (1963), Blow Job (1963) and Empire (1964). Sleep, famously, has a running time of 521 minutes, and consists of long take footage that shows Warhol’s friend and sometime lover John Giorno sleeping. To make the film, Warhol combined 22 shots, during each of which he homed in on different parts of Giorno’s supine form, from his face to his buttocks. The result is an obsessively voyeuristic film, the overtly boring quality of which paradoxically underlines the intense fascination that the object of desire can hold for an observer.

The cast lists for Warhol’s films, many of which were made at The Factory – the name Warhol gave his New York studio – read like a who’s who of the city’s alternative art scene in the 1960s and 1970s. They feature figures from the worlds of avant-garde film, performance and literature such as Jack Smith, Jill Johnston, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Gerard Malanga and Taylor Mead. The Factory itself performed an important networking function, becoming a place for people to be seen as much as for work to be made.

It was also an artwork in its own right. Warhol covered the walls of its first incarnation, which became known as the Silver Factory, in aluminium foil and silver paint, while the overarching concept of The Factory as a creative crucible enabled Warhol to manufacture the “superstars” that appeared in his productions, such as Edie Sedgwick and Ondine, by bringing individuals together and then featuring them in his productions. The Factory provided the stage on which Warhol developed a complex artistic persona that played with the celebrity status of the artist, and with the notion of the artist as impresario, models that practitioners from Tracy Emin to Jeff Koons continue to mine productively.

Warhol’s experimentation also expanded into performance. Between 1966 and 1967 he organised a series of multimedia events in collaboration with the Velvet Underground and Nico under the name Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI). The EPI immersed its audiences in frenetic environments of slide projections, sound, and strobe lighting. These sensory assaults were disorientating and destabilising, and have come to be understood as radical uses of technology and media.

In a very different instance of artistic collaboration, Warhol let the groundbreaking choreographer Merce Cunningham use his work Silver Clouds (1966) as the scenography for Cunningham’s 1968 dance RainForest. Silver Clouds consists of pillow-shaped Mylar balloons filled with helium that gently float around any given space. In RainForest, the dancers have to negotiate their unpredictable trajectories. The Silver Clouds were themselves developed in conjunction with the engineer Billy Klüver, who headed up the organisation Experiments in Art and Technology during the 1960s.

It is partly this openness to experimentation and collaboration that continues to ensure critical interest in Warhol, but his engagement with sexuality and gender is equally significant. The essays in the 1996 book Pop Out: Queer Warhol exemplify the ways in which Warhol’s work itself, together with his performance of his artistic identity, have had significant ramifications for understandings of the body, queer art histories and sexual politics.

Warhol’s reputation has not been unassailable. A dip in the art market in the 1990s led to prices for his works falling, while accusations of misattribution have been levelled at the Andy Warhol Foundation. Yet three decades on from his death, it often seems as if there are as many versions of Warhol as there are audiences.

While it might be the success of his works at auction that make headlines, it is the ideas, creative provocations, and the artist’s own studied resistance to interpretation throughout his interviews and writings which ensure that audiences remain intrigued.

Catherine Spencer is lecturer in modern and contemporary art at the University of St Andrews. This article was originally published in The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments