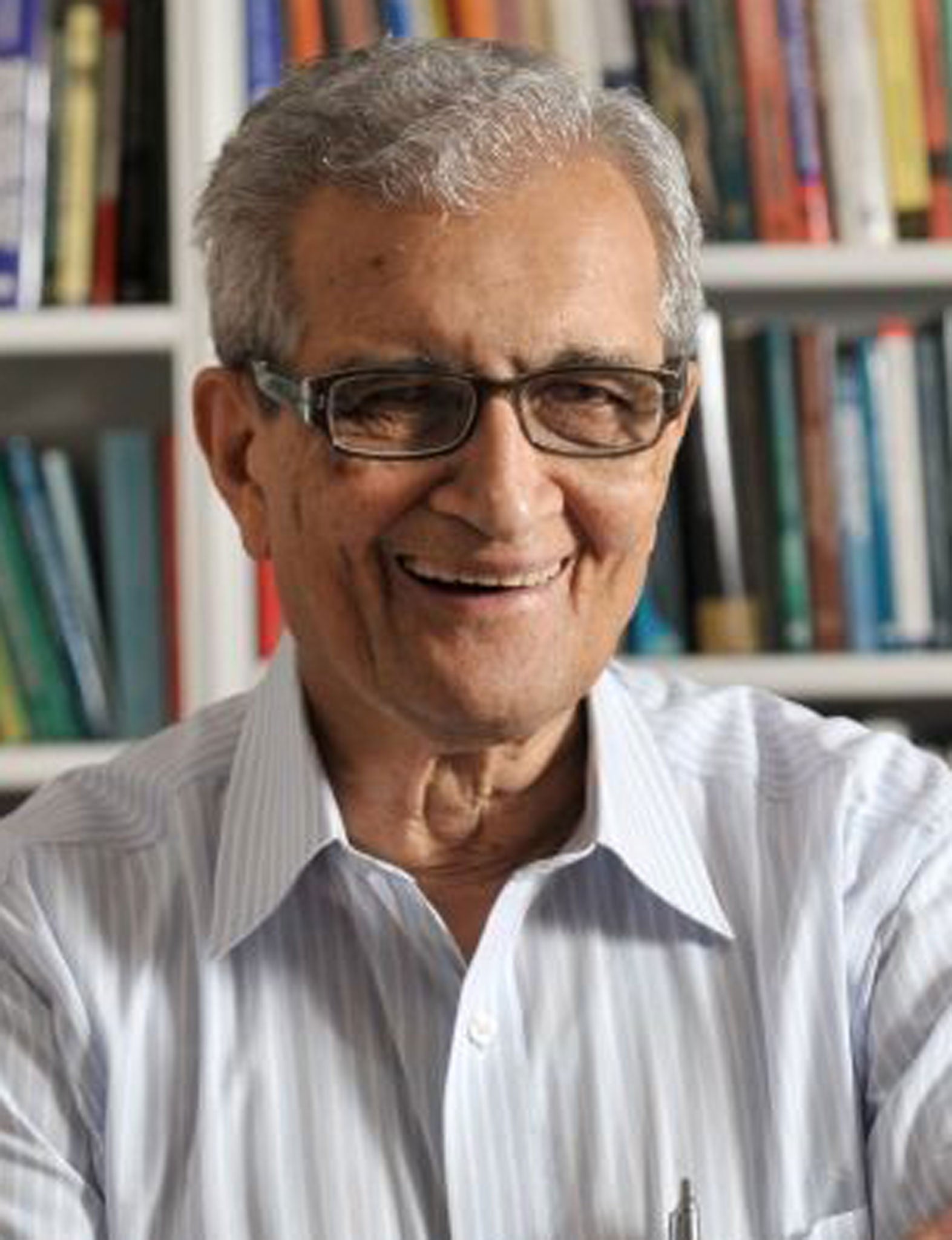

Amartya Sen: The taste of true freedom

The Nobel-laureate champion of democratic development for the world's poor, delivers a stinging indictment of India's unequal boom. Boyd Tonkin talks to him in Cambridge

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amartya Sen still takes his coffee strong and dark. After lunch in the hall at Trinity College in Cambridge, where his portrait – informal, gown-less, but with a sort of halo around it – hangs beside that of the other former Masters, he prepares for our interview with a slug of espresso. At Trinity in the 1950s (the Bengali teenage prodigy had arrived aged 19 from Presidency College, Calcutta in 1953), he learned to appreciate the brew in its even fiercer ristretto form from the great Italian economist Piero Sraffa: the brilliant maverick friend of Gramsci and Wittgenstein, and a fellow of the college for more than four decades. It was Sraffa, he tells me, who later recommended Sen for a prize fellowship with the proposition that “he is the only one of this year's candidates whom we might in the future regret not having chosen”.

Get money off Sen's work at the Independent's bookshop

For a revolutionary Italian thinker, that sounds like a very English understatement. Let's correct it. Without hyperbole, no postwar intellectual of the first rank has done more good for more people – above all, many of the world's poorest - than Amartya Sen. The first Asian to head an Oxbridge college, he served as Master of Trinity from 1998 – the year he won the Nobel Prize in economics - until 2004. He then returned to the professorship at Harvard he took up in 1986, but still spends stretches of the summer in Cambridge – where they have a house - with his wife, the historian Emma Rothschild.

Economist, philosopher, social theorist and peerless champion of the bond between development and democracy, Sen has across half a century of committed scholarship goaded governments, energised activists, and inspired research into the conditions that will liberate the poor not just to grow richer but, above all, to flourish in freedom and choose the life they value. He talks with affection about Morgan (EM) Forster, whom he met at King's in sessions of the Apostles - the fabled “secret” society. Well, few passages from India have turned out so well (although Sen pays long visits every year and has never given up Indian citizenship). One example: the UN Human Development Index grew out of work by Sen and his Cambridge student friend, Mahbub ul Haq. Another: if the world has got rather better at famine prevention, then in large part we have Sen to thank.

The terrible Bengal famine of 1943 – which killed perhaps three millions of the poor while leaving the middle class utterly unscathed - coincided with his childhood in Dhaka (now the capital of Bangladesh). His father Ashutosh was a professor of chemistry there, although Amartya was born (in November 1933) in the liberal haven of the Santiniketan campus, north of Calcutta. Santiniketan was founded by the great Bengali writer-educator Rabindranath Tagore – a profound influence on Sen in his secular outlook, passion for enlightenment and devotion to gender equality. Sen prefers Tagore over Gandhi as an Indian hero on several counts, above all education. The nation's universal schooling has lagged behind the rest of rising Asia, he argues, in part because Gandhi scorned its value: “India is an exception, and the exception had the sanction of the most powerful voice in India, namely that of Gandhiji.”

This shooting star from a clan of Tagorean teachers (his grandfather taught Sanskrit at Santiniketan) and rebels against the Raj blazed through a two-year first degree at Presidency College. Then came his first spell at Cambridge during a civil war between public-spending Keynesians and the market-minded “neo-classicists”.

That struggle never ends. Now, he calls the UK Coalition's austerity programme “an intellectual failure”. “Is there anything surprising in that it failed? Should a well-educated economist have been able to anticipate that? Yes. One doesn't have to be a Keynesian to see it. My friend Sam Brittan [a fellow-student at Trinity, and the economic guru who in the 1980s defended the Thatcher government's policies] is not a Keynesian, I think. On the other hand, he had no difficulty in seeing why austerity is a bad policy at this time.” Crucially, Sen's objections turn not on textbook wrangles but on the social damage done to the fragile fabric of an inclusive society: “Austerity is wrong, both on Keynesian grounds and on the grounds of underestimating what Europe has achieved, in a very hard way, over the centuries, and coming to fruition only in the second half of the 20th century.”

After his baptism of fire in 1950s Trinity, he was appointed to a professorship in economics at the new Jadavpur University - aged 23. Chairs and accolades galore followed: the fellowship at Trinity; 11 years at the Delhi School of Economics (1961-1972); professorships at the LSE (he lived contentedly in and around Kentish Town, where his wide progressive circle included the Miliband family), Oxford and Harvard - and then the mastership back at Trinity. Yet from his youthful adventures in “social choice theory” through his study of the practical “capabilities” to choose and act that make our formal freedoms real and magisterial works of exposition such as The Idea of Justice, early exposure to abject poverty and its offshoot - communal violence – has always shaped Sen's work.

During his Dhaka childhood, a Muslim labourer called Kader Mia came to the family home “screaming pitifully and bleeding profusely”. Driven by hunger, Mia had sought work in a Hindu area during a time of communal rioting. As Sen has written, “the penalty of that economic unfreedom turned out to be death”. Compassionate, hard-headed, pluralistic, Sen's work has never ceased to honour – and protect– every Kader Mia on earth.

In books such as Poverty and Famine and Hunger and Public Action, Sen makes the case that democracy – but, as he insists, it has to be a “functioning democracy” with an open clamour of diverse views rather than mere majoritarian tyranny– keeps people alive. After independence in 1947, an imperfectly free India saw no mass starvation; whereas Maoist China, after 1958, witnessed perhaps the worst famine (up to 30 million dead) in all of human history.

Freedom, an absolute good, also fills bellies. As we talk in his office in a Trinity hostel in west Cambridge Sen reflects on India's chequered post-independence record of human development. “No famine affects more than 10 per cent of the population… So how come that the government is so scared of having a famine – because, after all, it's a 10 per cent maximum? The reason they have cause to be worried is because of public discussion about the preventability of famines. The suffering of the victim becomes a cause with which the bulk of the population could sympathise. We do get that for famines, but we don't get it for chronic undernourishment; chronic lack of medical care; chronic lack of good basic education. That I think has to change. There's nothing to indicate we're not capable of doing it.”

With his long-term research collaborator Jean Drèze (Belgian-born, but also an Indian citizen), Sen has just published An Uncertain Glory: India and its contradictions. For all its intricate architecture of statistics (with scores of tables both in the text and as appendices), the book amounts to a charge-sheet. It accuses India's political leadership of a wholesale failure to spread the fruits of rapid growth. Despite the boom of recent years, it finds “a massive disparity between the privileged and the rest”.

Pithily (the work blends profound learning with striking expression), An Uncertain Glory castigates a lopsided Indian miracle that has led to “islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa”. Half of Indian households, Sen notes, still have no access to an indoor toilet.

At many points, he explores the rivalrous comparisons with China – which obsess India's political intelligentsia – to grasp the nature of his country's “unique cocktail of lethal divisions and disparities”. “It's not merely the fact that there are a lot of rich people,” he tells me. “China has more billionaires that India has, and Chinese inequality is no less that India's. But these basic amenities not being there – decent schools to go to; a decent health centre; a toilet inside your home… The lack of that in China is very little; whereas in India it's very large. Whatever the Gini coefficient [of relative equality] may say, there iss something vicious about Indian inequality.”

A flawed democracy has failed to deliver. “The tragedy is that we haven't been able to use the assets that we have better than the Chinese. In China, the elite talking to each other have been able to have a more humane system than the Indian democracy.” Yet, for Sen, freedom has seemingly failed because (as Gandhi quipped about Western civilisation) it has not properly been tried. Only a segment of society has made full use of their rights. He notes the chasm between mass protests in Egypt, Turkey or Brazil, where the middle classes voice demands on behalf of an entire people, and the “narrow-minded” pleas of India's aam aadmi (“common man”) campaigners. They want to keep middle-class entitlements such as subsided cooking fuel, diesel and electricity – “even though 30 per cent of Indians have no electricity connection”.

Sometimes, he acknowledges, middle-class revolt in India can lead to gains for all. He cites the fatal Delhi rape case of December 2012. “I think it's totally to the glory of the Indian mass movement that the brutal rape of this woman caused such a tremendous agitation. There's an element of enormous universality in her predicament. But the fact that she is from a… relatively more affluent family; that she is training to be a physiotherapist; that she can go out in the evening to watch Life of Pi, makes it much easier for the middle-class to sympathise with her. But, like in the case of [Suffragette] Christabel Pankhurst, the cause being represented is the cause of all women who are badly treated.” Faced with this groundswell of rage, Indian's free institutions moved, and fast. “That is part of what democracy allows, and in this case it was seized, and seized marvellously.” A swift judicial commission led to tougher legislation by the end of March.

Much of An Uncertain Glory pivots on a call for richer “public reasoning” in politics and the media as a route to enfranchisement for India's neglected poor, “left behind” by the assymetrical boom. “It's a seriously researched book – otherwise we wouldn't have had 60 pages of tables! – but it's also a manifesto. It's an agitational book”.

When I ask for a capsule summary to explain the lack of shared prosperity, he replies that “Inadequate political engagement is basically the headline. But I don't think you could get it into a four-inch space!” Communication always counts for Sen. Another figure who stirs fond recollections is Ian Stephens, editor of the Statesman in Calcutta, who in August 1943 broke the shaming silence of the Raj with stinging editorials that denounced the blindness of India's imperial rulers to the horror of the Bengal famine.

With An Uncertain Glory, Sen explains that “Each chapter has been rewritten about 10 or 15 times… to increase the communicability without losing the veracity”. I particularly enjoyed the flaying of India's escapist, celebrity-fixated newspapers (not counting noble exceptions such as the – entirely non-sectarian - Hindu in Chennai). Bollywood gossip pages will shriek about wardrobe malfunctions when “an overwhelming majority of the people… would have little idea of what a wardrobe is”.

Sen will travel to India to launch An Uncertain Glory in the country whose “jubilation” over an ill-shared bonanza he refuses to endorse. Given this harsh indictment, his lifelong allegiance matters. “I remain exclusively an Indian citizen… I stand in long queues to get into any country. It's a hard-earned prize. On the other hand, I can criticise India as an insider. I don't think the Indians are hostile to that.”.

One of the many surprising, even shocking, revelations in the book is that India has fallen behind its south Asian neighbours across a spread of social indicators. In particular, Bangladesh - his family homeland - has powered ahead on several fronts. Ruefully, and in the wake of his cricket-crazy nation's triumph at the ICC Champions Trophy, Sen wonders if Indians can get that hunger for success to work off the field as well. “If they can translate that competitiveness to quality of life, ask the question, 'Should we accept being beaten hollow by Bangladesh – not in cricket, but in life-expectancy, child mortality, gender equity?', and say, 'We mustn't allow it', then I would welcome that. I don't see it happening yet. But it might.” Undiluted, bracing but not bitter, the Sen brew still fuels change around the world.

'An Uncertain Glory: India and its contradictions' by Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen is published by Allen Lane (£20)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments