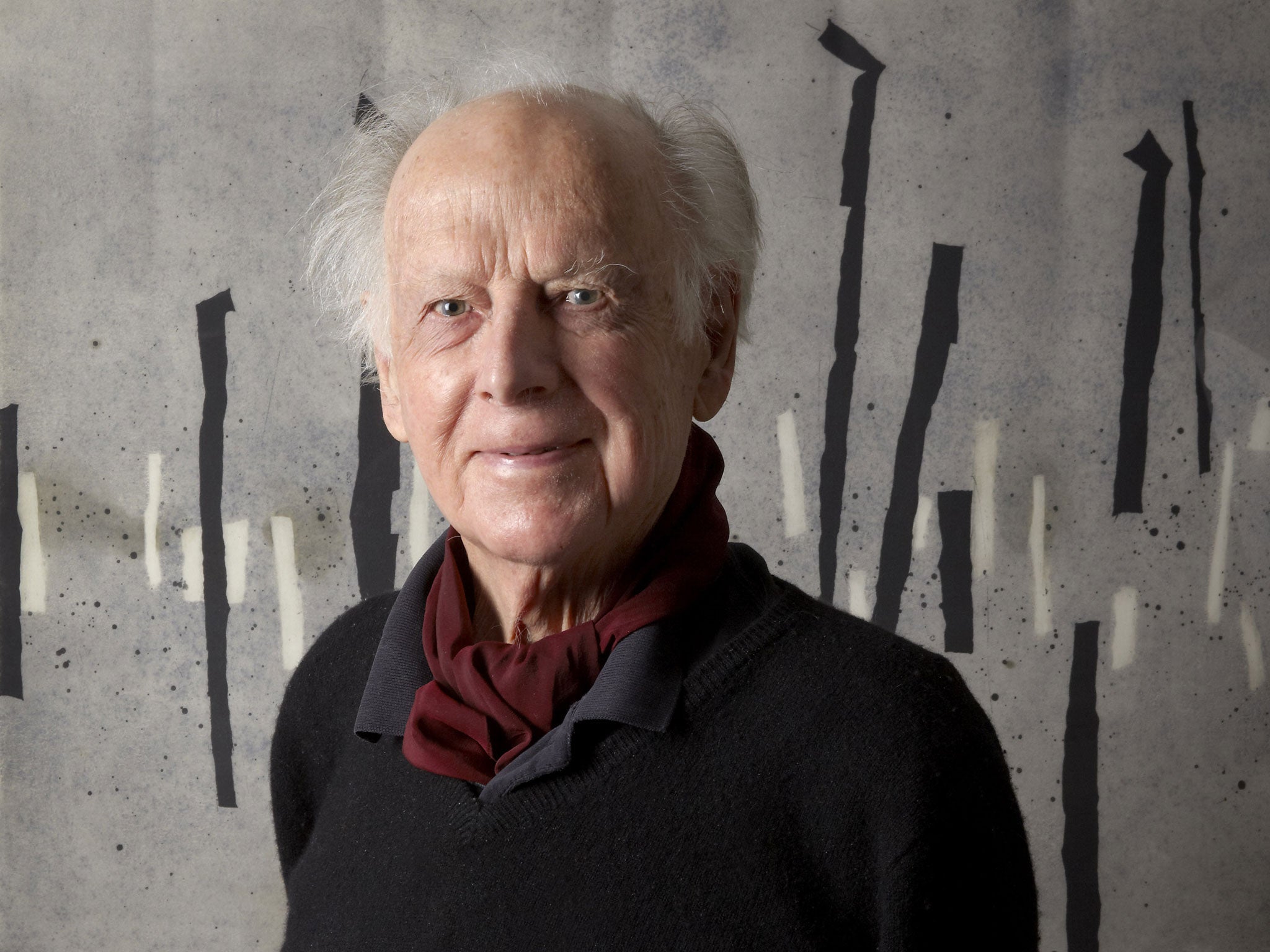

A £15m bequest from the collector who brought contemporary Chinese art home to Britain

Michael Sullivan left one of the world’s greatest archives of Oriental art to an Oxford museum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Through a quirk of fate, Michael Sullivan found himself transporting medical supplies for the International Red Cross in China in 1940. The experience would change his life. He returned to Britain married, with a passion for the country’s art that would see him devote his life to the subject and become a world authority on it.

Yesterday, it emerged that the academic bequeathed his private collection of 450 works to the Ashmolean Museum, creating “one of the greatest collections of modern and contemporary Chinese art in the world”. The Oxford museum, the oldest still operating in Britain, is currently having the collection valued, although early estimates put it at upwards of £15m.

The museum’s director, Christopher Brown, said the “extraordinary gift” made the museum “the key institution in this country for the display of modern Chinese art”. He also hopes that the bequest will help make it a “study centre for research” of the subject.

Professor Sullivan, who died in September at the age of 96, began collecting the works in the 1940s with support from his wife, Khoan. He owned pictures by some of Chinese modern art’s most important names, including Qi Baishi, Zhang Daqian and Fu Baoshi. His more recent acquisitions included Landscript by Xu Bing.

Professor Sullivan was instrumental in bringing these and other Chinese artists to the West. In 1959, he published Chinese Art in the Twentieth Century, the first book on the subject in any language. Shelagh Vainker, the curator of Chinese art at the Ashmolean, said yesterday: “As a scholar he was also groundbreaking. He was tremendously revered in China, and was a long-standing friend to the country.”

Last year, the National Art Museum of China in Beijing held an exhibition about Professor Sullivan and his collection of paintings, prompting the founding of a research centre into Chinese art in the capital. One artist, Qui Lei, Lei said the academic was a “real scholar”. “He has dedicated both his heart and intelligence to the study of Chinese art and has introduced Chinese art to both the West and the rest of the world,” he added.

Professor Sullivan was born in Toronto in 1916 and came to Britain with his family at the age of three. After leaving Cambridge University as a conscientious objector in the 1930s, he joined a group set up to provide medical supplies for the republican side in the Spanish Civil War.

The collapse of the republican forces meant that he joined the International Red Cross instead, and went to drive trucks carrying medical supplies in China, which had been invaded by Japan several years earlier. Professor Brown said: “It was obviously the great transformative experience in his life. He fell in love with China.”

He met Khoan, a bacteriologist, and they married in 1943. “It was love at first sight. Together they had many Chinese friends. She was very outgoing, and he always said she opened doors for him,” Dr Vainker said.

He built his collection through close friends in the Chinese art world. “He maintained friendships with artists despite not being able to go back to China in the 50s and 60s,” Dr Vainker added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments