Epsom Derby 2018: How William Powell Frith's famous crowd scene captured the excitement of the big race

British public satirised in beloved painting of historic thoroughbred horse chase

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This Saturday marks the 239th running of the Epsom Derby, a fixture of the English sporting calendar since the 17th century.

A favourite of the royal family for generations, the race at Epsom Downs, Surrey, was attended by Charles II and diarist Samuel Pepys in its earliest incarnation and was notoriously the track where suffragette Emily Davison met her death after throwing herself in front of George V's horse in 1913.

More commonly an occasion for fine hats, champagne and revelry, the spirit of the great day has rarely been better captured than in William Powell Frith's panoramic oil painting The Derby Day (1856-58). A popular favourite with the British public since it was first hung in London's Royal Academy in 1858, it initially attracted so many visitors that a rail had to be installed to hold back those leaning in for a closer look.

As historian Mary Cowling put it, The Derby Day was "recognised instantly as a unique historical record of a significant social event".

The crowd scene is satirical by nature, presenting a mocking cross-section of Victorian England at one of the few national events in which the upper and lower classes mixed socially. It also brilliantly conveys the abiding mood of excitement in the air, the palpable thrill of the British public at play.

Frith's incredibly detailed landscape features 88 individual characters, from top hatted gentlemen riding in carriages with their mistresses and courtesans to an acrobatic display, a family picnic, gamblers entering the Reform Club tent and watching a "thimble-rigger" while gypsy fortune tellers, cigar sellers and prostitutes appeal to the punters. A boy whose luck has run dry turns out his barren pockets in the foreground.

Amid the carnival atmosphere, Frith's underlying joke is directly before our eyes but nicely understated: everyone has their back turned to the race itself.

The painter (1819-1909) was interested in the Victorian pseudosciences of phrenology and physiognomy and believed that a person's inner characteristics were revealed in their physical appearance, hence his gleeful but lightly moralising emphasis on the Dickensian venality on show. It is no surprise to learn that Frith himself drew the revered novelist in 1859.

Frith had first visited the race in 1856 with fellow artist Augustus Egg and was moved to sketch the masses of visitors. "My first Derby had no interest for me as a race, but as giving me the opportunity of studying life and character it is ever to be gratefully remembered", he wrote in his 1895 autobiography.

Subsequently holidaying in Folkestone, he showed the drawing to his friend Jacob Bell, a wealthy chemist, who commissioned him to work it into a landscape painting 40 inches by 88 inches for the huge fee of £1,500.

The artist had previous form in this area having painted Life at the Seaside, Ramsgate Sands in 1854, which had been purchased by Queen Victoria, and would go on to paint Railway Station in 1862, an equally ambitious and chaotic vision of Britons boarding the Great Western Railway at Paddington. Were he alive today, Frith would no doubt have done a wonderful job of conveying the sea of revellers at Glastonbury.

Working on the painting over a 15-month period, Frith employed a number of models in his studio to pose as his various characters, including father and son acrobats from Drury Lane and a jockey named Bundy who endured such discomfort sitting on a hobby horse that he told Frith he "would rather ride the wildest horse that ever lived than mount the wooden one any more".

Frith also secured help from his friend John Frederick Herring ("one of the best painters of the racehorse I have ever known") and from photographer Richard Howlett, employed to "photograph for him from the roof of a cab as many queer groups of figures as he could" at the 1857 race.

A close variation on Frith's Derby Day was painted by Aaron Green in 1863, entitled Epsom Downs.

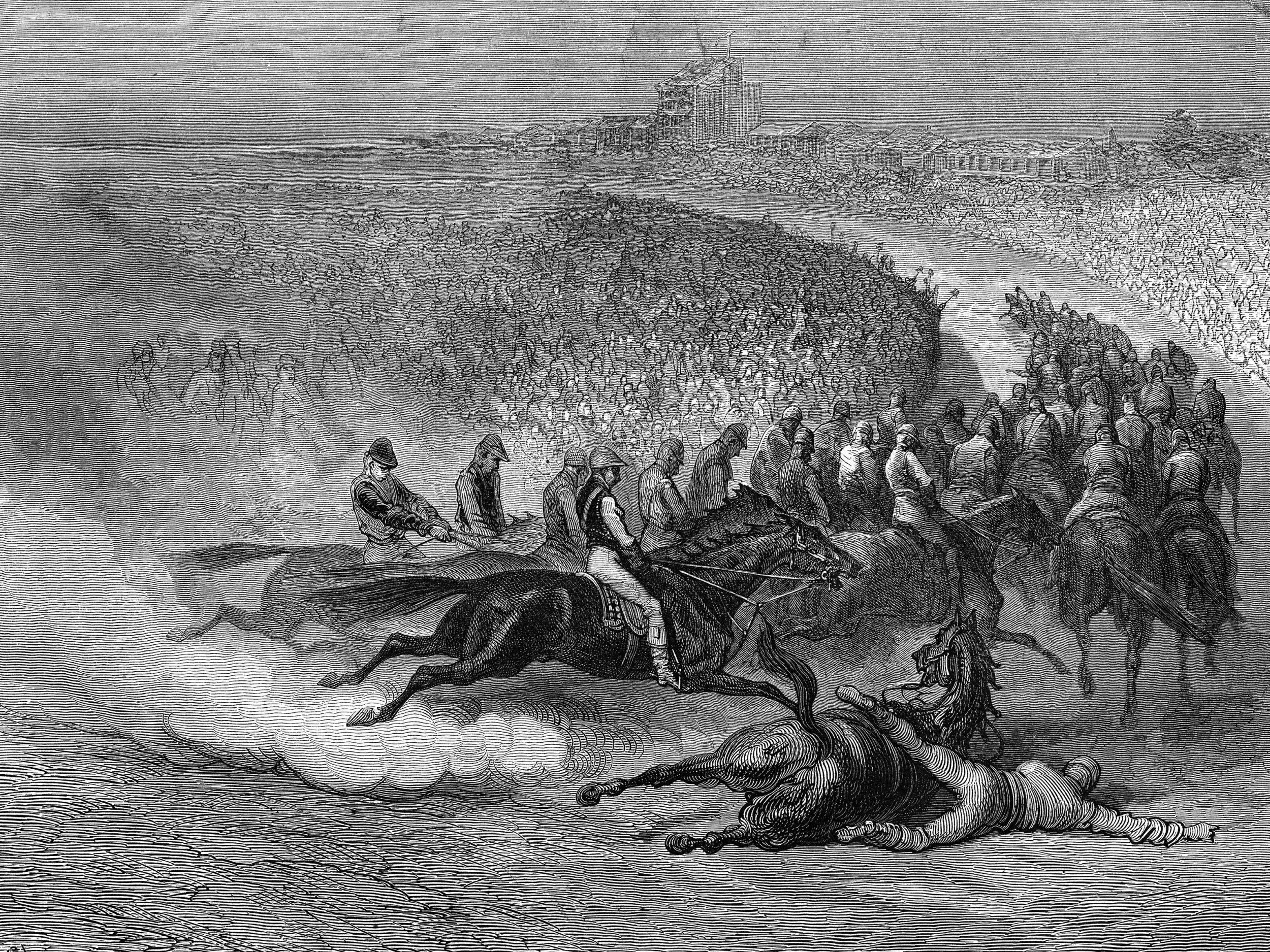

The French engraver and illustrator Gustave Dore would attend the great occasion in 1872 and chose the novel approach of actually sketching events on the track, depicting a jockey being tossed from his mount in a moment of high drama.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments