Asterix the Gaul makes comic comeback at London's Jewish Museum

A new exhibition on the creator of Asterix sheds new light on his Jewish heritage and inspirations for his huge body of work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

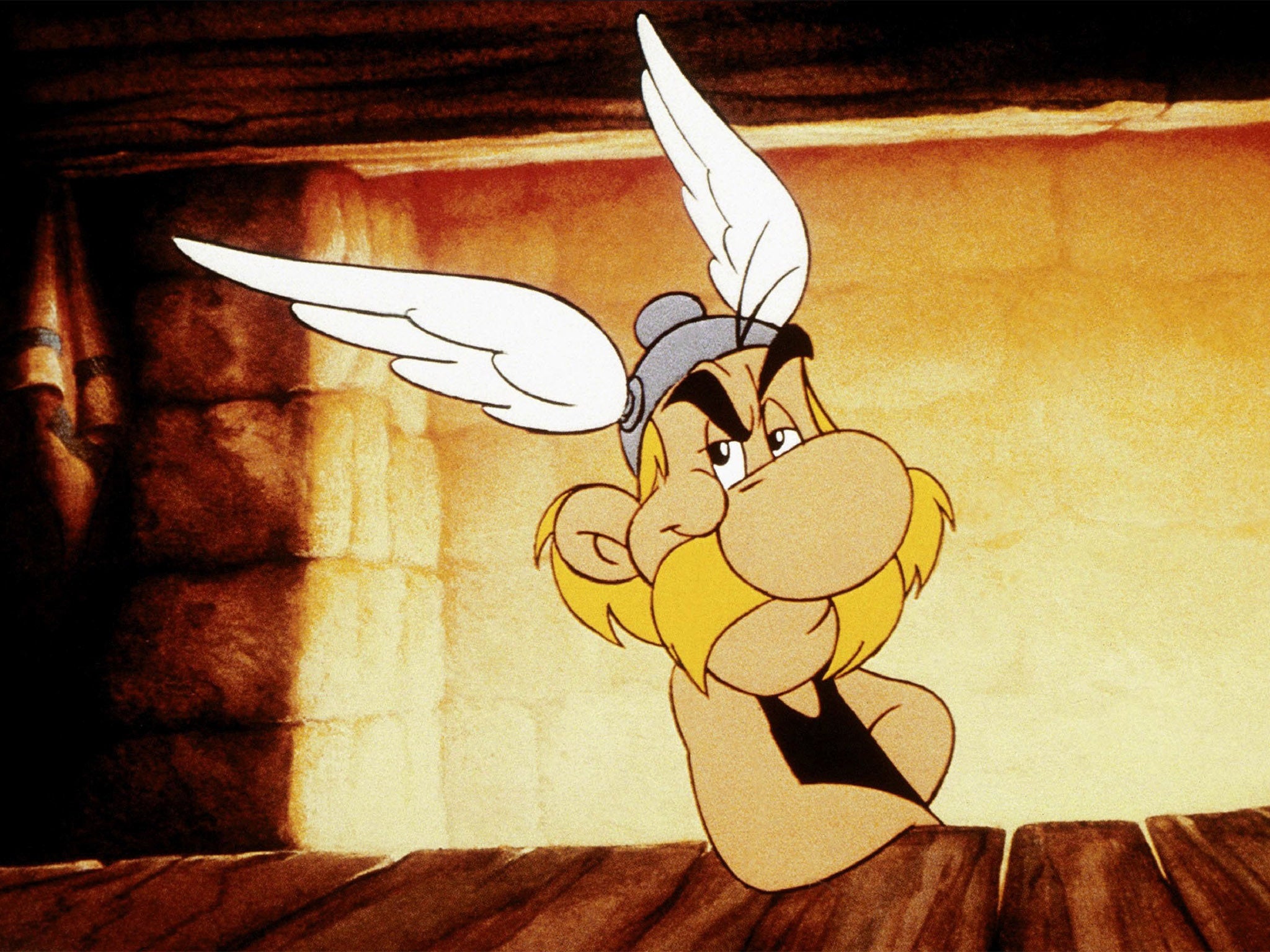

Your support makes all the difference.Asterix the Gaul is a much-loved comic character, the plucky, moustachioed warrior who leads a ragtag village in resistance against the occupying Roman forces, aided and abetted by a druidic potion that confers super-strength.

As a Frenchman born in 1926, writer Rene Goscinny’s inspirations for the beleaguered Gauls are perhaps easy to see. He left France while very young with his parents to live in Argentina, but grew up watching his homeland invaded and occupied from half a world away.

But there’s another dimension to Goscinny that is not as widely known; although born in Paris (and, indeed, something of a national hero to the French), his parents were Jewish immigrants from Poland and the Ukraine, and that’s why London’s Jewish Museum is staging the widest-ranging exhibition of Goscinny’s life and work ever to be hosted in the UK.

Among the 100 items gathered together at the museum are the typewriter on which Goscinny, who died in 1977, wrote his first Asterix stories, early examples of his own artwork, and – which any creative will recognise – a slew of rejection letters for his work.

Jo Rosenthal, head of exhibitions at the Jewish Museum in Camden Town, says that while a lot of the exhibition is naturally focused on Goscinny’s most famous creation, there’s so much more about him to discover.

“Everyone loves Asterix,” says Rosenthal. “The stories have been translated into 150 languages, he’s a widely recognised character. But a lot of people perhaps don’t know that the creator was Jewish. The reason why this exhibition is at our museum is because we’re tracing how his Jewishness impacted on Goscinny’s creativity.”

From an early age, living in Argentina, Goscinny had ambitions to be a cartoonist. His childhood sketch books are in the exhibition and they are a sometimes sobering mix of cartoonish creations and the influence of world incidents on the young creative.

“His books from when he was 15 or 16 feature drawings of Hitler and Stalin,” says Rosenthal.

“Goscinny observed the Second World War from a distance; his family had returned to France a lot before the war and had friends and quite a lot of family both there and in Eastern Europe, where his parents originally came from. Family members were interned, and some killed, in concentration camps.”

After the war, Goscinny moved to New York to try his luck in the cartooning world. Rosenthal says, “He had dreams of becoming the next Walt Disney, and in the exhibition we have some of his letters and CVs presenting his credentials to various magazines and organisations.”

Goscinny trained with renowned comics artists Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder, and continued to try to get work in New York.

Among the exhibits are rejection letters from The New Yorker magazine, and after amassing a pile of these Goscinny had a revelation that was to change his career: he realised that, while a fairly competent cartoonist, his strength lay more in the script-writing side of comics than the actual art.

It was then he began his collaborative relationship with the artist Albert Uderzo, who gave Asterix and co their distinctive look.

But Goscinny wasn’t content to simply try to sell the Asterix strips to existing publishers; he decided to set up his own magazine called Pilote, which was published in France in 1959, and the museum has managed to secure the very first typewritten pages of his scripts from which Uderzo worked for the inaugural Asterix stories that appeared in the magazine.

Much of the material in the exhibition has come from the Rene Goscinny Institute which was set up by Goscinny’s daughter Anne in Paris in 2016, but the Jewish Museum has also assembled a number of exhibits itself, including items from the collection of a British enthusiast, who wishes to remain anonymous.

Although Goscinny’s name is synonymous with Asterix, there was another comic series, featuring the cowboy Lucky Luke, for which he was equally famous in his native France. Goscinny didn’t create Lucky Luke; that was the Belgian cartoonist Maurice de Bevere, aka Morris, in 1946.

But Morris brought in other creators, including Goscinny, who wrote the adventures from the mid-1950s until his death in 1977.

Among his other work were strips for the Tintin magazine, including another collaboration with Uderzo about Oumpah-pah, a Native American. A lot of his work, says Rosenthal, reflected both his roots and the things he saw happening to his home country in the war.

“When you realise that both Goscinny and Uderzo were the children of immigrants, it does add a different dimension to their work,” she says. “Asterix perhaps has obvious parallels to what was happening in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. Oumpah-pah is similar, with Native Americans facing off against white settlers.

“Goscinny was something of a joker, there was a lightness to him. I’m not aware of him talking in detail about the dark days of the war, but there is no way that would not have affected him, and we can definitely read Asterix as being a reaction to that.”

Goscinny had returned to Europe in 1951, taking a job at the World Press offices in Belgium, where he first met Uderzo. He was summarily fired from his job for trying to start an artists’ union.

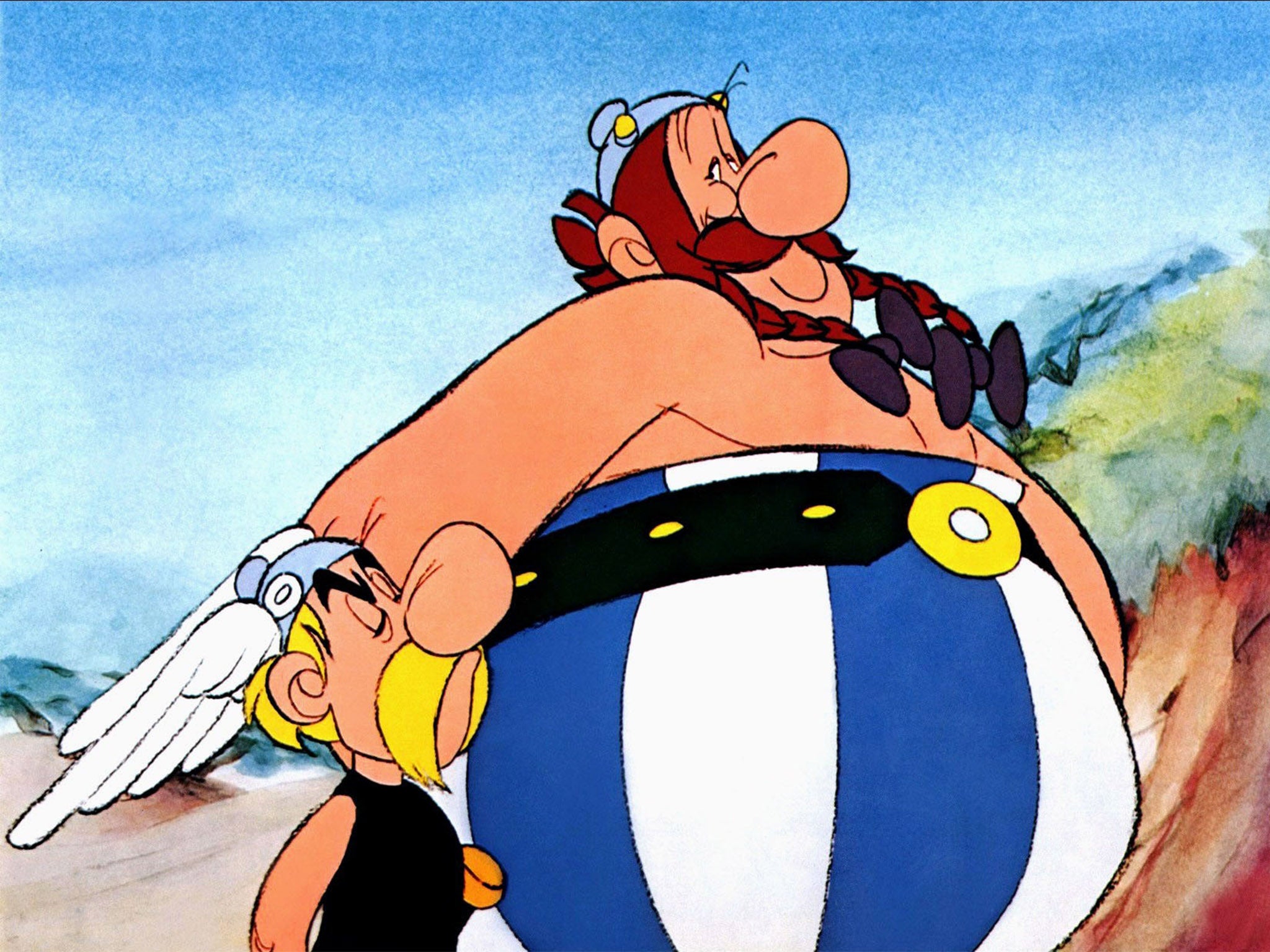

More than 100 movie adaptations of the Asterix story have been made, and many will remember the animated versions from their youth and the series of live action movies that began in 1999 with Gerard Depardieu as Asterix’s absolute unit of a best friend, Obelix.

Rosenthal herself didn’t grow up on Asterix comics, but has come to the character, and Goscinny’s work, through working with the museum exhibition. However, now she’s a firm fan, and expects anyone who walks through the doors between now and the show’s end in September to be the same.

“He seems to have been a funny, sweet, kind of guy,” she says of Goscinny. “He’s an absolutely fascinating character and has led such an interesting life. That’s one of the joys of curating such an exhibition; you immerse yourself in the subject through all these amazing exhibits and items.

“Anyone visiting the exhibition will come away with a strong sense of Goscinny’s life story as we take them on a journey from his birth to the legacy he left with us in the present day.”

Goscinny died after suffering a heart attack while undergoing a routine stress test at his doctor’s, in 1977, but by that time he was already a giant of French popular culture, and his daughter Anne, an author in her own right, helped maintain that legacy with the setting up of the institute in Paris.

Rosenthal’s sentiments are echoed by Abigail Morris, director of the Jewish Museum, who says: “We have gathered materials of an unprecedented scale and richness for this exhibition, which highlights the brilliance and creativity of a remarkable writer, the child of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, who made a huge contribution to European culture.

“Characters like Asterix humorously yet shrewdly tell the story of a marginalised people under threat and how a small village use their wits to resist an occupying force. It’s a story which appeals not only to all ages but resonates with readers all over the world.

“Visitors will learn not only about the outputs of Goscinny’s prolific career but also about the cultural heritage that lay behind his genius.”

Goscinny’s works have sold more than 500 million copies worldwide, and since 1996 the Rene Goscinny Award has been given annually to young comic writers at the prestigious Angouleme International Comics Festival.

He is buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Nice, and while his contribution to the world of comics has never been in doubt, now fresh light is being thrown on the influences, inspirations and motivations of his work thanks to his Jewish heritage.

Asterix In Britain runs at London’s Jewish Museum until 30 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments