There hasn’t been a major group show of Abstract Expressionism in Europe since 1959

Works by Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and other artists are being exhibited together for the first time in 57 years. What do we gain from seeing these works as a group, asks Holly Williams?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1959, New York’s Museum of Modern Art sent an exhibition to eight European cities – concluding at London’s Tate gallery – with the calmly self-assured title of The New American Painting. It featured 17 artists, most of whom were associated with Abstract Expressionism, including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still.

While critical reactions on the continent veered between stunned admiration and outrage at this show of large, bold, abstract works (one French critic asked: “Why do they think they are artists?”), the mood back in New York was one of jubilant triumph. Abstract Expressionism had proved itself.

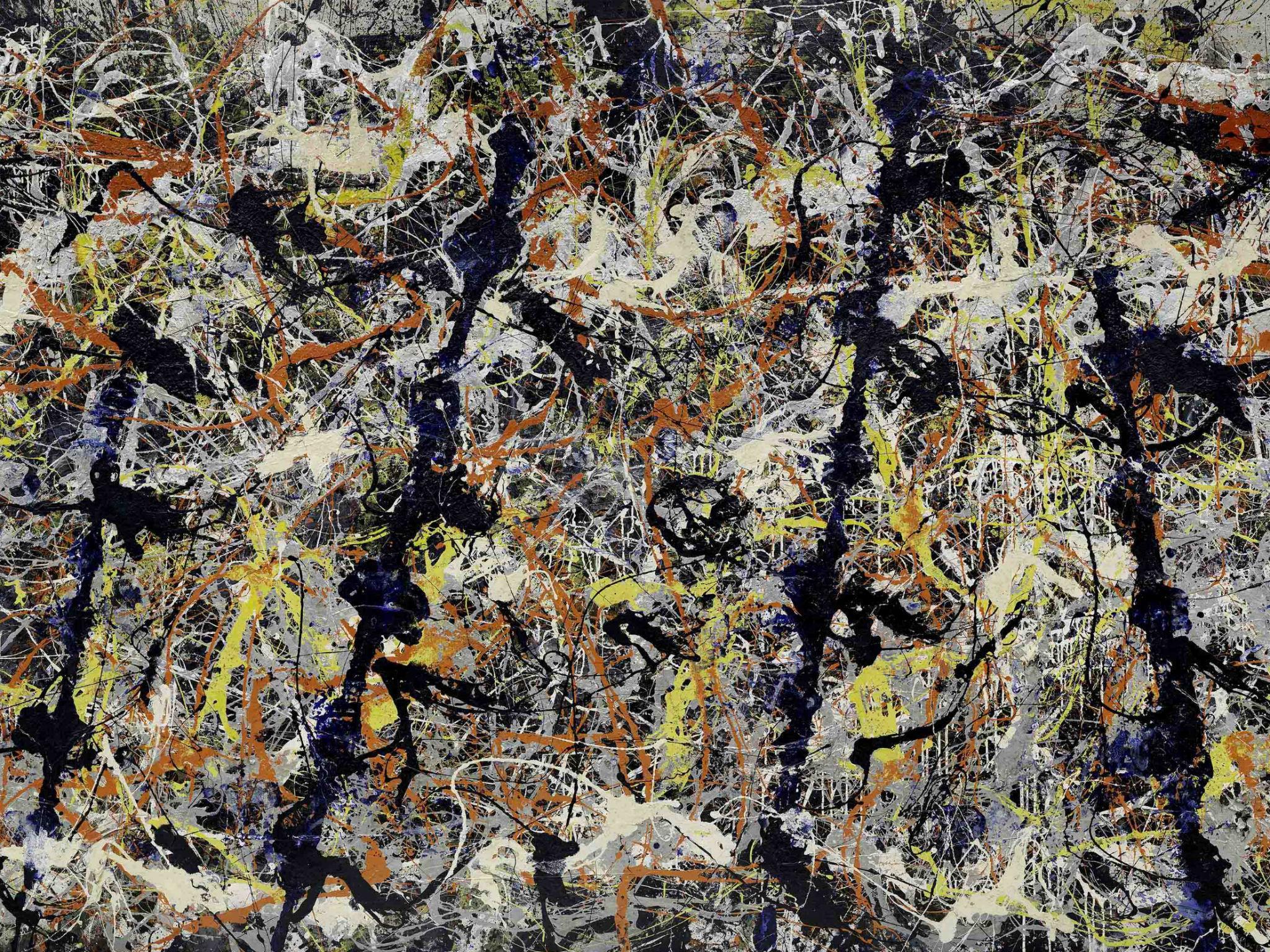

They were right to feel confident: Abstract Expressionism went on to be one of the most widely known movements of 21st century art. Pollock and his paint splatters are practically proverbial today. Yet – astonishingly – there hasn’t been a major group show of these artists in Europe since that touring blockbuster.

That changes this week, when the Royal Academy in London brings together works by both core and more peripheral artists for a new group show called simply Abstract Expressionism. While many of the individual artists have had substantial solo shows in the UK over the years, this offers a rare chance to consider their work together, to allow their paintings to really speak to each other.

“This is a group exhibition because Abstract Expressionism was a group phenomenon, involving painters, sculptors and photographers and stretching from New York City to the West Coast,” says Dr David Anfam, art historian and co-curator of the show, who adds that, given it is 57 years since the last group show, “the time is ripe to do this at the RA”.

Abstract Expressionism was never a self-defined movement; while many of the artists knew each other well, they had no manifesto like, say, the Futurists. The work is varied: De Kooning’s frantic, grotesque Woman paintings don’t appear to have much in common with, for instance, Newman’s more minimal, soothing “zip” canvasses.

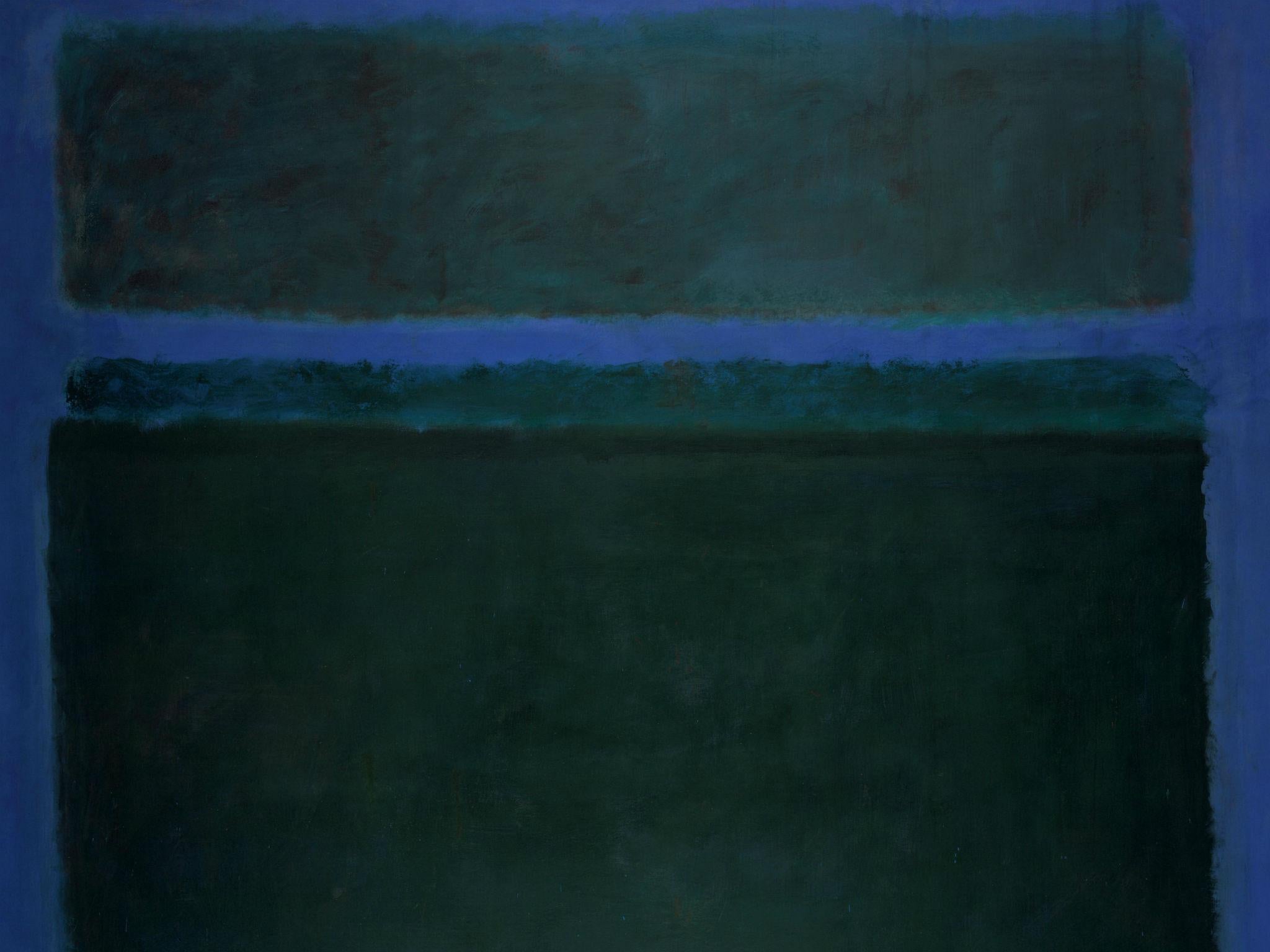

Still, you can say that, starting in 1940s New York, a coherent group of artists began to produce work of a certain vitality, scale and urgency. Whether through intense fields of colour or dynamic drips, slashes and splashes, these abstractions sought to express a human truth, and to elicit a powerful emotional response in the viewer.

As Rothko asserted: “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on – and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions.”

Showing these artists together will demonstrate the breadth of work that falls under the Abstract Expressionism banner, and the show has a revisionist side, paying attention to overlooked artists – women especially – and including photography, works on paper and sculpture as well as monumental paintings.

But, crucially, it should also allow the artworks to connect, to hum and resonate with each other. The exhibition is deliberately organised to reveal lines of influence and aesthetic assonance in a group of artists who, as Anfam explains, “were often very much aware of each other, socially and artistically”.

“By showing the artists together it is possible to establish new sight lines and experiences – for instance, connecting Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, who were both involved, in their different ways, with developing extremes of colour and similar visual absolutes,” he continues. “Throughout, the curatorial premise is to put the various works in dialogue with each other: Arshile Gorky leading on to his disciple de Kooning, [David] Smith with Pollock, and Pollock himself with his wife Lee Krasner.”

There are rooms devoted solely to Still and to Rothko – but they adjoin each other, with the curators hoping it will be “possible to make visual connections between the two artists for those who want to do so”. Other rooms are thematic: one, entitled Darkness Visible, will bring together works by several of the Abstract Expressionists who, at different points in their careers, “explored the hypnotic power of blackness and shadowy depths of colour”.

That there should be artistic overlap is no surprise; although not confined to New York, many Abstract Expressionists lived and worked there in the Forties and Fifties, and would gather in cheap bars and cafés to drink hard, and talk harder.

Gorky, De Kooning, Smith and others would eat at Romany Marie’s, a gloomy little café in Greenwich Village, and afterwards many tables would be commandeered at the seedy Waldorf Cafeteria for heated discussions about art, amid a clientele of cabbies, bums and pickpockets.

At the end of 1949, De Kooning, Kline, Reinhardt and others established The Club in a loft in the East Village; it hosted Wednesday evening discussion groups on lofty topics such as the function of art, and its moral value. Weekends there, however, were for dancing, the alcohol chipped in for by whoever was least broke, and served in paper cups. More booze-fuelled fervent discussion would continue in the cramped Cedar Street Tavern, where Rothko, Newman, Kline, de Kooning and Pollock all would gather.

It’s no wonder artistic influence – not to mention petty jealousies and deeper feuds – spread among them. “It was Clyfford Still who influenced Mark Rothko’s breakthrough into abstraction during the second half of the 1940s,” suggests Anfam. “Some of David Smith’s sculptures also clearly echoed Pollock’s paintings. And Pollock and De Kooning famously became rivals who each vied to be the numero uno, as it were, of the whole group.”

By the mid-Fifties, Abstract Expressionism might have been rising in artistic importance, and in financial value, but the relationships within the loose group were falling apart. Still wrote letters denouncing Rothko’s desire for “bourgeois success”, while Newman also claimed Rothko had stolen from his paintings. Newman tried to sue Reinhardt for publishing a sneering account of him in a satirical piece about the New York art scene, and he and Still also fell out over accusations of copying.

Hey, no one ever said being part of a major artistic phenomenon would be easy. But given there were such intense relationships, it’s surely surprising that there haven’t been more group shows. Aside from the physical considerations – securing loans of such vast canvasses isn’t easy – why might this be the case?

“Abstract Expressionism was so huge that it soon got taken for granted throughout the art world,” suggests Anfam. With many other, also highly significant, movements rapidly following it – from Pop to Minimalism to Conceptualism – he thinks Abstract Expressionism got somewhat elbowed out of the way.

“Now is the moment to see its breadth and depth afresh. It’s an art of enormous ambition and originality, with which we need to reckon once more.”

Abstract Expressionism is at the Royal Academy in London, 24 September to 2 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments