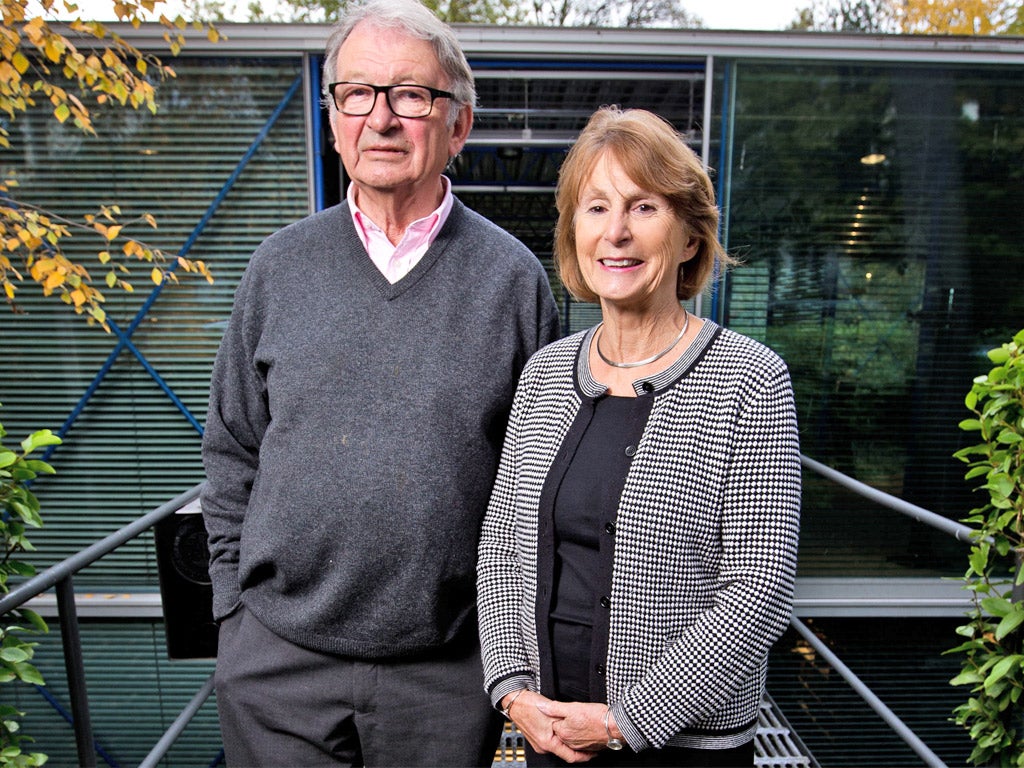

The Brits Who Built the Modern World and 49b - the house built by High Tech designers Michael and Patty Hopkins

Jay Merrick hears the gospel according to the first couple of British architecture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The house in Hampstead has no name. Just a number: 49b. Not that you would dream of giving this kind of house a name like Dunroamin. In 1975, when it was built by two up-and-coming architects, the only name that might have done was “Future Shock”.

This house, designed by Michael and Patty Hopkins, embodied the potential of modern architecture stripped to its essentials. It’s little more than a grid of skinny, blue-painted steel posts, beams, and thin metal sheets of insulated siding, flat roofing, and glass. There are no decorative architectural details and only two colours: blue and metallic grey.

The line between industrial design and architecture with a capital “A” was well and truly breached here. The house is a genuine icon of the High Tech movement in architecture, and the Hopkinses – now Sir Michael and Lady Patty – will be two of the six architects featured in The Brits Who Built the Modern World, a BBC4 series and exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects taking place in February. The others are Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw and Terry Farrell.

High Tech design – of which this handful of British designers became the focal point in the 1970s – rejected commercialised modernist architecture, which had overwhelmed the corporate world. The movement also rejected Brutalist design, which aimed to create a new kind of rugged, stark concrete and glass architecture that characterised 1960s new towns such as Harlow and Cumbernauld, and also the Barbican estate. High Tech took the famous modernist dictum “less is more” and emphasised “less” as never before. This breed of designer was as interested in rubber gaskets and factory insulation panels as it was in Rome or Venice. Michael Hopkins, for example, had his lightbulb moment at the age of 14, when his contractor father showed him some moulded cement; a few years later, working for an architect in Bournemouth, he was allowed to design a boat shed and became fascinated by the asbestos kit-of-parts system he had to use.

Michael and Patty Hopkins went on to work for Lord Foster, the most internationally influential architect of the last 40 years. The early practices of Foster and Rogers were the starting-points for many of today’s most successful architectural practices, including John McAslan + Partners, which created the new wave-splash concourse canopy at King’s Cross station.

The future of the built environment would, they believed then, take modular, prefabricated form. It would be ultra-lightweight, and the difference between architecture and engineering would be irrelevant. And High Tech would be done rapidly. “We decided to build the house this way because we’d blown all our money on buying the site,” says Michael Hopkins. “So we had to do something very quickly.”

“It isn’t really High Tech,” adds Patty. “It’s really very basic 16th-century engineering.” The remark highlights a trademark of High Tech: simple structural frames, held together by sophisticated joints, rods, and tension cables – just as old oak beams are locked together by crafted mortice-and-tenon joints.

Between the 1960s and the early 1990s, this future-proofed handful of British architects delivered the High Tech goods: the Reliance Controls Factory, jointly by Foster and Rogers; Foster’s Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank headquarters; Hopkins’ Schlumberger Research Centre in Cambridge; Grimshaw and Farrell’s Herman Miller Factory.

One of Grimshaw’s directors, Nevin Sidor, recalled the vibe in practice’s early days: “We all had an obsession with the manufactured object, sharply made. It’s almost as if we wanted to freeze the showroom gleam.”

It was a gleam that began with High Tech’s icon of icons – Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in 1851: iron and glass, prefabricated on site, and based on a structural system Paxton sketched on blotting paper in the hotel at Derby station.

The High Tech ethos surfaced in other equally extraordinary historic structures, such as the Eiffel Tower, the impossibly delicate-looking diagrid of the Shukhov radio mast in Moscow in 1922, and in North American grain silos lauded by the architect Le Corbusier in the 1920s.

Today, the High Tech gleam has mutated: it’s about the use of the latest materials, structures, and energy-saving systems as efficiently as possible – but, too often, in buildings that are tricked up as architectural icons. There are no tricks at 49b. Instead, a sense of something simultaneously lost, and found. The house, like The Brits Who Built the Modern World, still packs a punch.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments