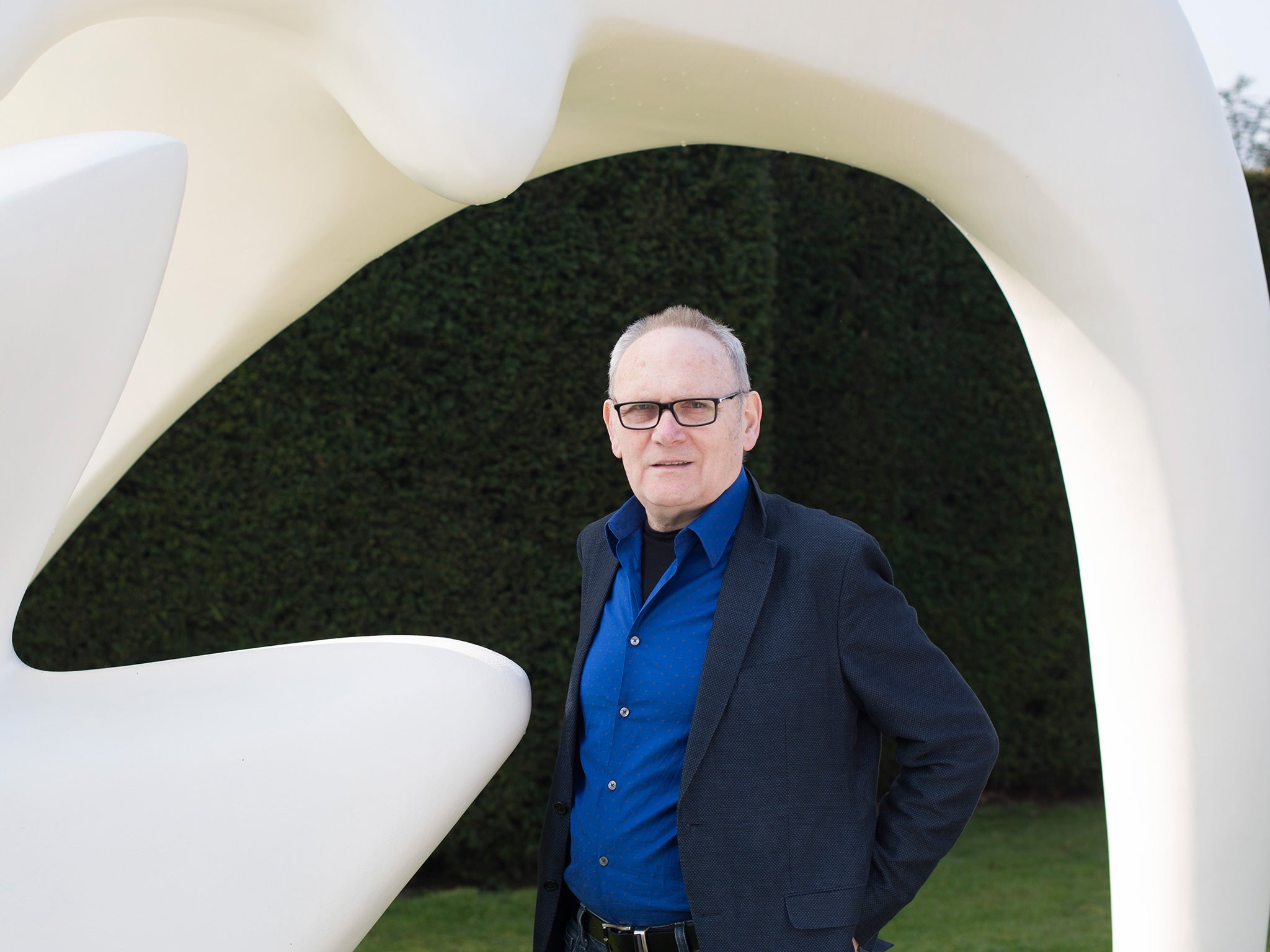

Founder of Yorkshire Sculpture Park Peter Murray: ‘You can’t build a Northern Powerhouse if arts and culture are ignored’

He has grown the place from nothing to become museum of the year - now he appeals for the region to receive its fair share of arts cash

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Peter Murray set up the Yorkshire Sculpture Park 38 years ago, even some of the artists weren’t sure it was a good idea.

Henry Moore, whose hulking bronzes now stud the rolling fields outside Wakefield, was a fan, but Anthony Caro preferred to show his more intricate pieces in a “very controlled environment”, according to Murray – in other words, indoors and away from the sheep.

The Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) has long since won over the doubters. It was crowned museum of the year last year by the Art Fund Prize, beating London jewels Tate Britain and the Hayward Gallery. At the same time, annual visitor numbers have spiked 24 per cent to pass 400,000 – of whom 10,000 come from overseas. This summer the park will celebrate the 60-year career of Caro, who died in 2013, in a major retrospective.

Yet challenges remain on the regional arts scene, funding being the biggest one on the sculpture park’s otherwise sunny horizon. Murray, 73, sipping coffee on the balcony of the visitor centre that looks out across the greenery, has advice for George Osborne as the Conservatives return to government with the aim of rebalancing the UK economy by creating a “Northern Powerhouse”.

“The rebalancing has got to include culture,” he says. “If you look at London, one of the reasons it is a global player, not just because it has massive investment, it is because there has been a huge investment in culture there. The rebalancing that I would like to see is both in economic and cultural terms. They go hand in hand.”

Murray adds: “It is much more complicated than saying the North or outside of London should get more but I think one has got to look at the amount of subsidy per head that the London population gets as compared to the North of England.”

In 2010, the museum had to cope with a 20 per cent cut in public funding including regional grants. Until 2018, its Arts Council England cash has been frozen at £1.3m a year, meaning it must raise two-thirds of its operating costs to keep going.

The attraction claims to be worth £10m every year to the local economy. The 500-acre site has become one point of a “Sculpture Triangle” that takes in the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, the Hepworth Wakefield and Leeds Art Gallery, creating critical mass to get it noticed internationally. It has gained greater fame than the long-standing “Rhubarb Triangle”, a cluster of farms which capitalise on the wet, cold winters of West Yorkshire to produce a large forced rhubarb crop.

The £35m Hepworth, named after sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who like Moore, was born locally, opened in 2011 – the biggest art gallery to be built since the Hayward on London’s South Bank in 1968. Having seen what Murray achieved, it has been heavily backed by the local council to regenerate a tired end of the city. “One could say that the success of the park has given a number of people the confidence to invest,” he says. “Way back, the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds came about partly as a result of the success of the park and I would say that is true of the Hepworth too.”

Born in Middlesbrough, Murray came to study a postgraduate course in art education at Bretton Hall, a teacher training college outside Wakefield, and never left. While he lectured there, he got thinking about how his students could engage children in great works and opened an exhibition in the grounds.

“The idea of bringing it here was for children in particular to experience the kinaesthetic aspects of sculpture – to be able to walk around it, to see the change in light quality,” he says. Armed with just a £1,000 grant, it was slow going at first.

“There was not a great deal of support from the art world and a lot of public opposition to the idea of putting rusty bits of metal and suchlike in an 18th century park.”

The irony is that it is because of the rusty metal that the park has been pieced back together into its original Capability Brown-inspired form after it was parcelled up after the Second World War. Over the years, Murray has bought 230 acres with a lottery grant, done deals with farmers and other private landowners and taken over management of some more that was owned by the council.

Now the sculpture park has 500 acres to play with, featuring five indoor galleries including a chapel reopened as a new space with an exhibition by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei.

“When people think of this estate they think of something that is traditional but when it first came into existence it was very cutting edge. We are trying to hold on to history but at the same time trying to ensure it exists in the 21st century. There is a balance of nature and art but also the past, present and future. It is important to get that vitality.”

The development goes on. When the college closed 10 years ago, Wakefield Council bought Bretton Hall back and is now in negotiations with a property firm to turn the Grade II-listed Georgian mansion into a hotel so that when visitors travel in for openings they have somewhere to stay close by. And how long will Murray go on? He is cagey about handing his life’s work over to anyone else, although he is keen to talk up the team around him, and enthuses about the next generation of British sculpting talent such as Roger Hiorns and James Capper.

“We’ve still got things to do,” he says. “I am trying very hard not to finish things off but to tidy up around the edges.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments