Cedric Price: The most influential architect you've never heard of

The eccentric genius who inspired the Millennium Dome, the London Eye and the Pompidou Centre gets his own exhibition in Cambridge

During his career as an architect Cedric Price suggested building a large dome as an entertainment space, putting a giant ferris wheel by the Thames and constructing an arts centre where flexible space was maximised.

Decades later, the Millennium Dome, the London Eye and the Pompidou Centre duly punctuate the landscapes of the British and French capitals, but the cigar-chomping visionary who anticipated them remains largely unrecognised.

His former college at Cambridge University is now seeking to begin to redress that balance by mounting an exhibition explaining Price’s life and work as a radical architect who was ultimately “as famous for not building things as he was for building things”.

The retrospective at St John’s College, where Price graduated in architecture in 1955, looks at the continuing influence of the trenchantly iconoclastic architect who is credited with a succession of important developments in his field and yet built little.

Among his innovations was his strongly held belief that architects overrated their ability to change the world and should consider the idea of not building when looking at a project.

Price, the Staffordshire-born son of another architect who helped design Odeon cinemas in the 1930s, is best known in terms of his own work for the “free flight” aviary constructed from aluminium pyramids and draped with netting at London Zoo.

But curators of the exhibition argue that the architect should be equally remembered for his talent for standing convention on its head with projects ranging from a university on rails to a fun palace complete with an inflatable conference centre that nonetheless never made it off the drawing board.

Mandy Marvin, who curated the exhibition, running until January, said: “Price was like a grain of sand that irritates the oyster - the oyster in his case being the architectural profession. He was always provoking thought and response within the profession, including successfully lobbying RIBA to allow architects to recommend not to build.”

A lifelong socialist who likened life under Margaret Thatcher to living in an occupied country, Price designed around the philosophy that buildings should serve the needs of those that use them and be either transformed or demolished when they no longer matched their purpose.

Among Price’s most pioneering designs was his so-called fun palace, to be built on the banks of the Thames in 1961 for the avant garde theatre director Joan Littlewood, through whom he met his partner, the actress Eleanor Bron. The structure, which had no permanent roof and consisted of moving walls and floors without doors to control entry, became known as an anti-building for its ability to be dismantled and reconfigured.

This concept of permanent flexibility was reflected in a second project for a new form of university dreamt up by Price for his native Potteries area of Staffordshire, which was based on the idea of a reviving post-industrial regions by transporting places of learning on rail.

Rejecting the proliferation of new universities and polytechnics in the 1960s, Price said he wanted to get away from building “more monuments to a medieval sense of learning”. His Potteries Thinkbelt was to have been based on the region’s network of disused railways with carriages used as classrooms with fold-out workspaces and inflatable lecture theatres.

But along with the fun palace and other concepts, the rail-based university never came to fruition for lack funding or enthusiasm from commissioning bodies.

He was furious with the now defunct Greater London Council for reneging on the promise of a South Bank site for the fun palace and was scathing of his fellow architects, arguing his radicalism stemmed only from their stolidity.

As he once put it: “I’m only radical because the architectural profession has got lost. Architects are such a dull lot and they’re so convinced that they matter.”

The exhibition suggests that this deeply philosophical architect, who famously had a cigar and a glass of brandy for breakfast, instead laid the groundwork for buildings and concepts only realised much later.

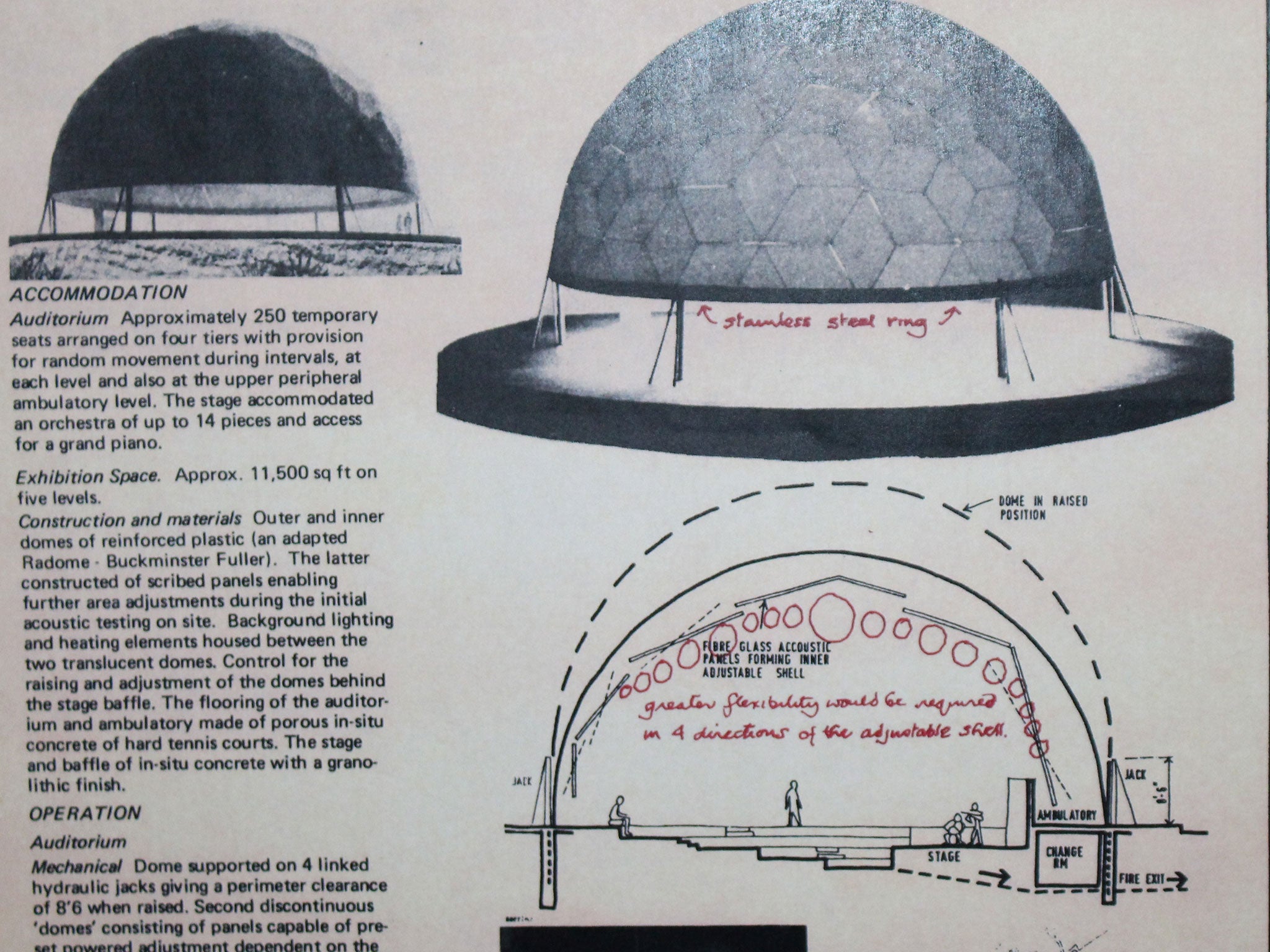

The fun palace is regarded as a precursor for the inside-out styling of the Pompidou Centre, while Price also proposed a flexible geodesic dome as an auditorium and entertainment venue which anticipated the once-troubled but now successful Millennium Dome or O2.

In 1983, Price also suggested a dramatic shake up of the way visitors experienced London’s South Bank by asking “why should people always have to look up?” His sketched solution of a ferris wheel with a succession of viewing pods bears a remarkable resemblance to the London Eye.

Price, who for four decades worked from the same offices in Bloomsbury, and ushered a succession of renowned contemporary architects including Will Alsop through his doors, was nonetheless stubbornly modest about his work.

When proposals emerged to list his Inter-Action Centre, a multipurpose community centre built in London’s Kentish Town in 1977 with an intended lifespan of 20 years, he strongly argued for its destruction. It was duly demolished in 2003, the year of his death.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments