Concrete trends: How Brutalism came back into architectural fashion

Graphic designer Peter Chadwick’s new book is a love song to the beauty of concrete. Kashmira Gander looks at the social issues underlying the rehabilitated aesthetics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

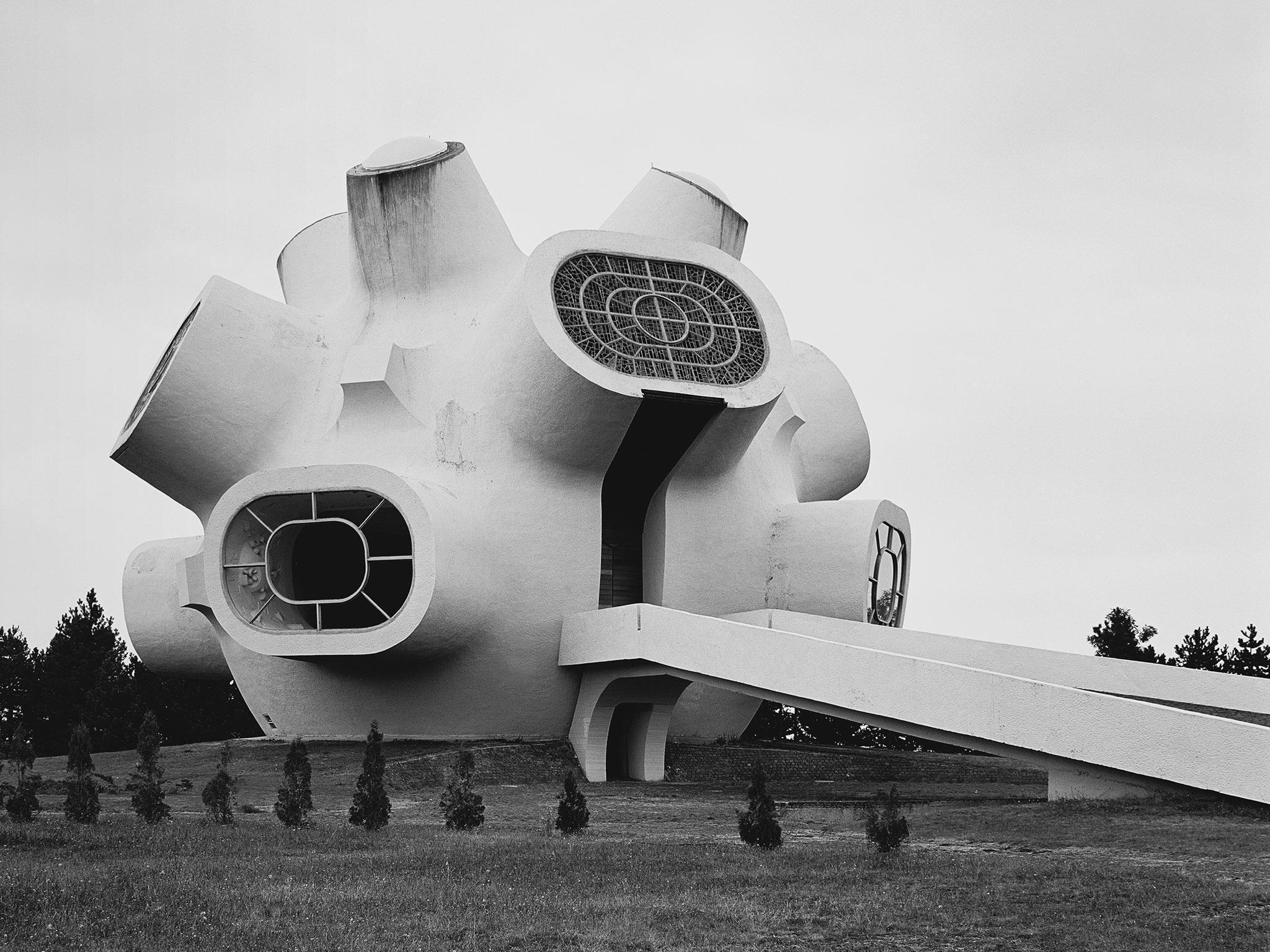

Your support makes all the difference.If there was any doubt that Brutalism is at the height of mainstream architectural fashion, the latest in a flurry of coffee-table books celebrating the once-divisive style provides all the proof needed. Over more than 200 pages of photographs depicting concrete behemoths, This Brutal World is graphic designer Peter Chadwick’s love letter to Brutalism and the stark, industrial beauty of concrete: a utilitarian material without context, unlike wood or marble, made simply using sand, water and limestone.

Almost as soon as it was built in the post-war years, most Brutalist architecture was widely regarded with such disgust that it seemed as though crime and ugliness seeped from concrete. How fortunes have changed, as panellists at a sold-out discussion to launch This Brutal World – hosted at the Royal Inistitute of British Architects and attended by 400 people – remarked. Who, apart from architecture nerds and trail-blazing tastemakers, would have bothered to turn up to such an event just five years ago? Now, the National Trust hosts tours of Brutalist estates, while the Brutalism Appreciation Society Facebook page has almost 40,000 members.

The style was pioneered in post-war Europe, notably by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier and his 1952 Unite d'Habitation social housing complex in Marseille, complete with utopian “streets in the sky”. At the time, governments were forced to throw up buildings to replace what conflict had erased. During that first wave, architects regarded their task as a moral one, and upheld a socially-progressive vision of society.

The new welfare housing lifted people out of slums and into exciting new homes fitted with mod-cons such as bathrooms and heating. Museums and venues, such as London’s Southbank Centre squatting grandly beside the Thames, helped to bring arts and culture to the masses. The British architecture critic Reyner Banham, who coined the description, said: “In order to be Brutalist, a building has to meet three criteria, namely the clear exhibition of structure, the valuation of materials ‘as found’ and memorability as image.” Quite simple, really.

Designers around the world, from Brazil to Japan, went on to adopt the style, as Chadwick demonstrates. But he contrives to make Brutalism as timeless as it is global (the monochrome images, organised according to form rather than chronology detach the buildings from their context and completion date). And in fact, there is no indication in his book whether any of the structures are still standing.

If they are, their once fresh facades may well be grey and water-damaged now, the utopian dream too often become a dystopian nightmare. But Brutalism isn’t always unforgiving. The power plant in Rodal, Norway, looks like a grey flying saucer that crash-landed into a mound and thrust its legs into the ground to support itself. Similarly, the Egg Centre for the Performing Arts in Albany, New York, looks a vehicle for alien invasion, with its smooth, asymmetric bowl-like curves.

Then there’s the satisfyingly child-like geometry of the Bangladesh National Capital Complex in Dhaja, with simple triangles, rectangles and semi-circles cut into a facade that ethereally floats above a lake.

Suddenly desperate to run your hands against cold, rough concrete and skip through streets in the sky? You’re not alone. Indeed, once-hated Brutalist social-housing buildings in the UK have become some of the most sought-after addresses in Britain. In a peculiar twist, the style is no longer controversial, while the socially-progressive ideals of its architects risk being forgotten.

The multi-coloured renovation of Sheffield’s Park Hill estate – which was shortlisted for the prestigious 2013 Royal Institute of British Architects’ Stirling Prize – is now home to the creative and middle-classes. Meanwhile, social housing tenants of east London’s Balfron Tower are being “decanted” – or evicted, to you and me – to make way for more affluent residents. And at the same time, its almost identical west London twin, the Trellick Tower, has shaken off its tabloid nickname of “Terror Tower”, as ex-council flats are snapped up by design-conscious incomers.

Not that they don’t suffer for their status. Over the past decade, private owners within the Trellick complex have been hit with hefty bills to cover building works and maintenance – for which councils tenants aren’t liable. (However, one’s compassion for them might be diminished by the fact they’ve seen the value of their flats rise by hundreds of thousands in that time).

As for less metropolitan sites, their future seems uncertain. Prime Minister David Cameron earlier this year vowed to destroy Britain’s “brutal high-rise towers” and “bleak” estates. But others called him out for social cleansing. Nicholas Ruddock has lived in London's Robin Hood Gardens Estate, which is due to be demolished, since 1982. He told artist Jessie Brennan for her book Regeneration! Conversations, Drawings, Archives and Photographs from Robin Hood Gardens: "what the outsider sees is a harsh brutal concrete exterior, now dirty grey, [but] as occupants we are looking out, secure in our citadel, overseeing the locality, as occupants of a castle might have in the medieval period."

That’s certainly a description which would have chimed with the architects of the pristine, private Barbican complex in the City of London. (A barbican is a defensive tower or wall in a castle.) Described as one of the modern wonders of the world when it was opened by Queen Elizabeth in the 1980s, its sparkling appearance has barely changed. But then, its residents can afford the upkeep. And they’re neither criminal nor ugly. Are they?

'This Brutal World' by Peter Chadwick (Phaidon, £30) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments