The ten best underrated buildings in Britain

A new exhibition tells the story of of our modern nation via 100 of its most inspiring buildings. Here we pick our 10 favourite "wildcards"

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Are we beginning to see that Britain’s most beautiful, useful and inspiring buildings can be from decades rather than centuries ago?

There seems to have been a sea-change in attitudes towards 20th-century architecture in recent years, and that’s in no small part down to the 20th-Century Society – a conservation charity, founded in 1979, that campaigns against the wanton destruction of modern buildings and public art. Last year, it helped to get Grade II listed status for Preston Bus Station, thus halting its planned demolition, and it continues to support the campaign to prevent Birmingham’s Central Library from being bulldozed. Both are buildings that take effort to understand, as much as any Shakespeare play, and the society encourages this public engagement by running tours and talks about how to read modern buildings and empathise with them.

To celebrate the century of architecture under its remit – it aims to protect buildings from 1914 on – it is putting on a show at the Royal Academy. Opening next week, 100 Buildings 100 Years will tell the story of our modern nation via 100 of its most inspiring buildings, one from each year. But although many architectural stars feature on the list, from the De La Warr Pavilion (1935) to the Eden Project (2001), more interesting are those unsung gems of 20th-century architecture that are finally being given their due. Here are 10 of my favourite “wildcards”:

1. Odeon, Bradford (1930)

2. Finsbury Health Centre, London (1938)

This was more than just a doctor’s surgery. Berthold Lubetkin’s north London health centre presaged the NHS by a decade and, indeed, helped to inspire it. Inside this building, ordinary people were able to access all sorts of free health care in a clean, fresh and modern environment. The building, and the idea of it, should be a source of immense pride as a symbol of what the country achieved when it set its mind to caring for all of its people equally.

3. Smithdon High School, Hunstanton (1954)

4. Our Lady Help of Christians, Tile Cross, Birmingham (1967)

Basil Spence’s rightly-celebrated post-war reconstruction of Coventry Cathedral is only a few miles down the A45, but it’s worth remembering that Britain was building churches all over the place well into the Swinging Sixties. Here, at Tile Cross, east of Birmingham’s city centre, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s son Richard built a Catholic church topped with a swooping concrete-and-copper roof that wouldn’t have looked out of place at the new motorway service stations that were popping up at the same time.

5. Newcastle Civic Centre (1968)

6. Preston Bus Station (1969)

7. Trellick Tower, London (1972)

J G Ballard’s dystopian 1975 treatise High Rise (currently being filmed by Sightseers director Ben Wheatley) must have been influenced by this beast of a block of flats that he passed on his drive home to Shepperton. The architect in High Rise is obviously based on Trellick’s mastermind Erno Goldfinger, who embraced a future of sci-fi, of concrete, of affordable homes for everyone. Today, the once-hated block is a highly sought-after place to live.

8. Central Milton Keynes Shopping Centre (1979)

Decanting inner-city residents to outer-city estates can play havoc with people’s spirits, as Lynsey Hanley detailed in her brilliant book Estates. But new towns, especially Britain’s final stab, Milton Keynes (butt of jokes, home to concrete cows), could work. Residents liked their life with a garden here. And they liked shopping in the bright, airy mall by Stuart Mosscrop and Christopher Woodward, which originally had no outside doors so you could stroll in at any hour. It’s also notable for its graceful portes-cochère – pavement shelters to stop road-crossing pedestrians getting drenched.

9. New Art Gallery, Walsall (2000)

Galleries were the sine qua non of millennial regeneration and Walsall’s was an attempt to create a Guggenheim Bilbao in the Black Country. Nearby West Bromwich had the same light-bulb moment with its (now closed) arts centre, The Public, which saw its architect Will Alsop have a rare off-day. But, up the A4031, Caruso St John succeeded with a neat, boxy little building by the canal which houses good art too – the Garman Ryan Collection, with works by Degas, Monet, Picasso and Turner.

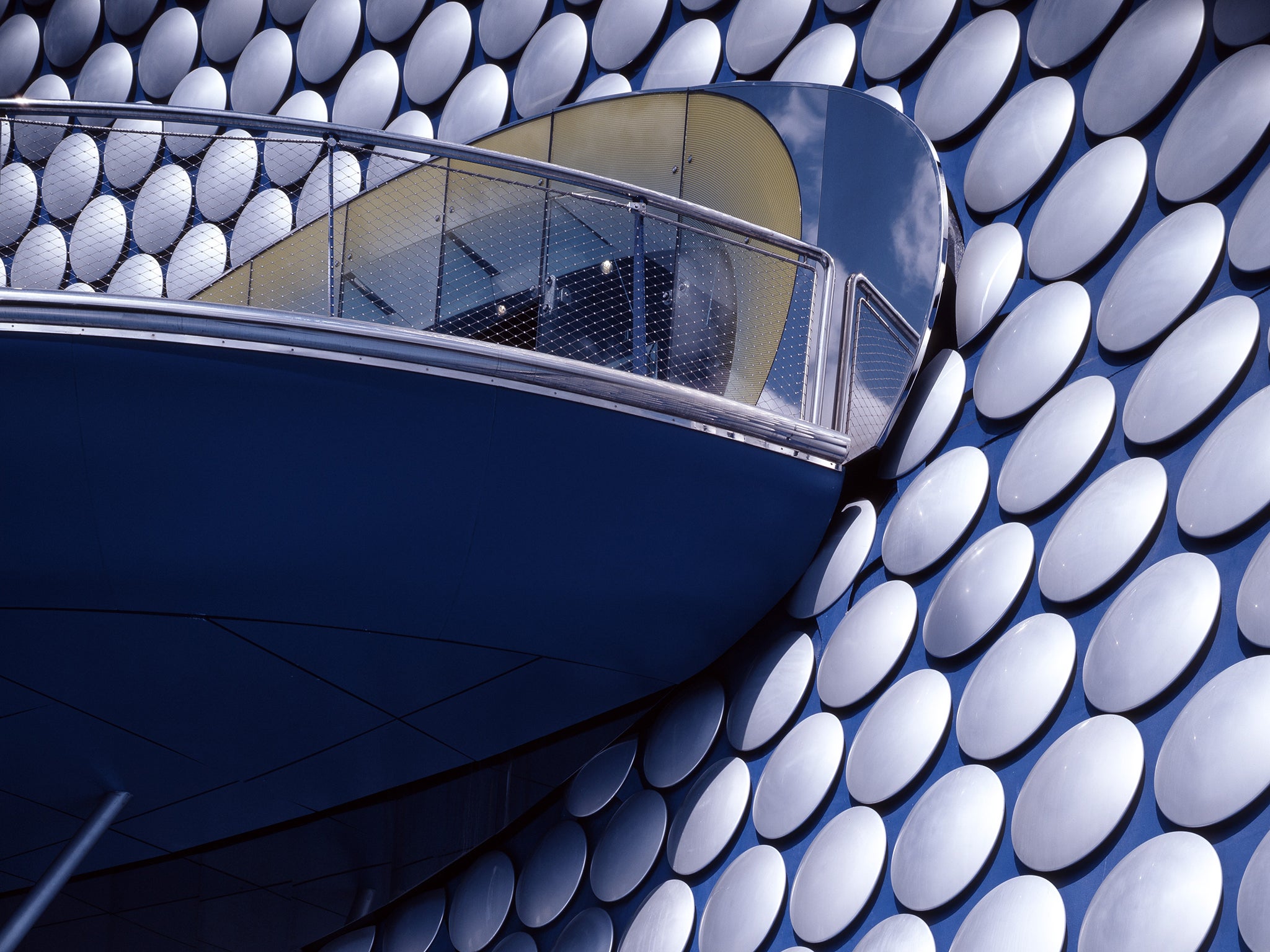

10. Selfridges, Birmingham (2003)

‘100 Buildings 100 Years’ is at the Royal Academy, London. 11 Oct to 1 Feb 2015 (royalacademy.org .uk/exhibition/100-buildings-100-years)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments