David Bowie: New book explores how childhood influenced his life and identity

In his new book, celebrated psychologist Oliver James not only claims that we can all renew ourselves if we emulate the role-playing David Bowie – but that heredity is a negligible cause of mental illness. So where's his head at?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One thing first. Oliver James says his new book, Upping Your Ziggy, is no quickie cash-in. An unexpected combination of self-help manual and David Bowie psycho-biography, it was planned and mostly written well before the pop star’s death this January.

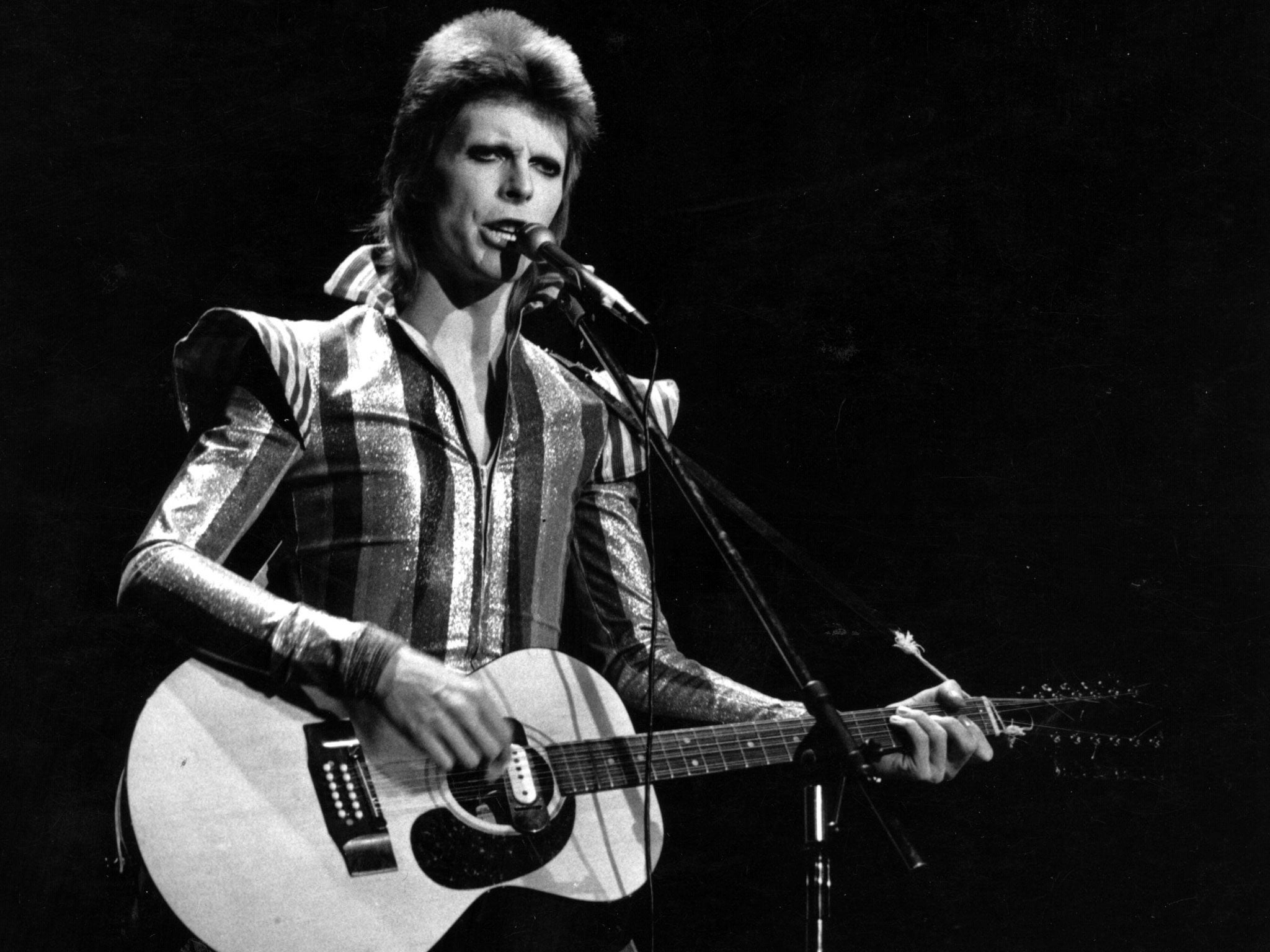

That would seem to check out. Bowie is, all too obviously, prime material for pop psycho-biography. He was the most self-knowing and referential of pop stars. (Who else would have apostrophised a song as “Heroes”?) He was a star often referred to only by his surname — and not the one he was born with, Jones, but one he only took on after several years in the pop game. A man of many “personas” – to use the word in the book – from Ziggy Stardust to Thin White Duke and the punning Aladdin Sane.

The year before he died, Bowie described himself as “a collector of personalities”. All too often, it is clear, he confused himself with his collection. On tour with his Spiders From Mars, he would only respond to the name Ziggy.

The central thesis of the book comes in these two sentences. “Through adopting personas, Bowie succeeded in changing who he was. He did this through integrating his childhood experiences into the adults he pretended to be.” By extension, the book claims, this is something we can all do for ourselves. Take our past troubles, create imaginary selves who can make their way through those troubles and use them to make ourselves afresh and psychologically healthier.

Oliver, 62, was “always a great fan of Bowie”, back to when he was at Cambridge, around the time of Ziggy Stardust. Three years ago, he found himself wondering about Bowie’s childhood. And there came the genesis of the book. “All I need to know is the childhood and I can write the story.”

I call him Oliver because that’s what I’ve always called him. I worked with him closely in the mid-1990s, editing his writing for a Sunday magazine. We got on. We had both studied psychology – one reason I was put to working with him – and he had worked as a clinical psychologist.

Unlike many of his colleagues in the inward-looking world of psychology and therapy, Oliver was never afraid of being a public figure, with opinions to go with it. As early as 1982, he was on TV, heading a series about childcare. He had written newspaper columns. He had made documentaries about psychopaths and Britain’s (then) rising levels of violence. In The Chair, a BBC2 series of intense, psychoanalytically inclined one-on-one interviews, he had even made Peter Mandelson cry.

The two major themes of his subsequent book-writing career were already at embryonic play in the articles that I edited. Theme one: capitalism is bad for you – whether you are a beneficiary or a victim of its inequalities. (Hence his 2007 book Affluenza, its follow-up The Selfish Capitalist and his description of the 2008 financial crisis as a case of “corporate psychopathy”.)

Theme two: families matter. He has titled not just one but two books after Larkin’s "This Be The Verse": They F*** You Up: How to Survive Family Life (2002) and How Not To F*** Them Up (2010). It’s the main take-home of Upping Your Ziggy.

One particular piece of Oliver’s that I remember editing was centred on the natural experiment that the world of psychology knows as twin studies. That is, find two twins separated at birth and see how similar and different they are. Twin studies address the question: are we born the way we are, or are we made into the way we are? Nature or nurture?

That debate is pretty much settled in matters physical. Both my sons, for example, are colour-blind because their maternal grandfather was – like haemophilia, colour-blindness is a genetic condition that only appears in males but is inherited via the female line. But in matters psychological, the nature-nurture argument is still fresh and alive. Some studies seem to indicate, for example, that temperament or even political preference may be genetically determined.

Oliver takes a different view. He says the maths is wrong, that small similarities mask substantial differences. In the nature-nurture debate, he thinks the environment is not just primary but paramount and our genes effectively non-players. It’s an argument that he has played out both in the national press and the pages of The Psychologist. “Scientific illiteracy” was one comment thrown at him, by a pro-nature psychologist. Ouch.

Oliver is, I say to him, a hard nurture man. He doesn’t like that description. He just thinks he’s right; and he says the evidence bears him out:” What I am saying is uncontentious. Significant hereditability hasn’t been found.”

For what it’s worth, I sit in the middle of the nature-nurture debate. But knowing Oliver’s own formative environment makes me no wiser about his own psychological traits. When I first met him, he was introduced to me as “not a typical Old Etonian”. Which is precisely the same thing that’s been said to me of every Old Etonian I’ve ever been introduced to. So, a charming paradox: a typical Old Etonian is one who is not a typical Old Etonian. And we’re back to “personas”.

Upping Your Ziggy emerged from a plan to write something about family politics but, as Oliver read and researched, he realised there was “something about Bowie’s life and family history that was exceptional – surprise, surprise, given how exceptional he was”. That something was schizophrenia. Mental disorder ran through Bowie’s family – and is echoed in the star’s many personas.

Bowie’s childhood was certainly a caution. His half-brother Terry became schizophrenic and committed suicide in 1985. His grandmother, who parented Terry, was harsh, mocking. Three maternal aunts went mad. There was – according to the grandmother – a family curse, which Bowie believed.

Others might see it more as a genetic destiny. There are many studies which indicate that there is, at the very least, an element of hereditability in schizophrenia. Oliver rejects this, arguing that the reason it runs in families is that so does dysfunction and corrosive parenting – nurture not nature.

Oliver gives a compelling, and generally psycho-biographically convincing, account of the way Bowie’s familial history threaded through his lyrics, performances and personas. (Many of his songs made reference to Terry’s experiences, from “Bewlay Brothers” to “Aladdin Sane” and “Black Country Rock”.)

It makes sense of the chaos and charms of his most productive years, from Hunky Dory to Lodger. The drugs, the sex, the clothes, the poses adopted and the idiocies expressed – on the attractions of fascism, for example. And it makes clear how different the second half of his personal life was: seemingly drug-free, steadily married to one woman, with new children and an almost anonymous existence in Manhattan.

The book also gives something like guidance on how we might manage this in our own lives – up our own Ziggies, as the title has it. This strand draws on Oliver’s own family life. For example, his son’s persistent insistence that he was, at least some of the time, a squirrel called Nibbles and on what he has heard and seen in his clinical practice, in Chipping Norton. (Not that he is “part of the Chipping Norton scene” of our Old Etonian Prime Minster.)

As Bowie remade himself through a series of personas, so has Oliver, in his own less dramatic way. To start with, a clinical psychologist working in an NHS hospital. Then a TV documentary-maker and presenter. Then a writer: first a journalist, then author. Four years ago, though still writing, he returned to his original trade. He is now a psychotherapist, his life and work generally tied to the 50-minute hour and its mini-dramas. (When we talked, on the phone, he had to break off for his next appointment.)

“Working with clients, you see the most extraordinarily huge power that there is in developing a dialogue between different parts of self and reintegrating them, producing new personas and pushing old ones into the background,” he says.

But what the book doesn’t give is a satisfactory explanation of how Bowie used his personas to get from that early fractured self to the more integrated one of his later years. There is a before and an after but no clear mechanism for how and when the change happened. It’s possible, though, that I was an unknowing, uncomprehending witness to a significant element of the transformation.

I encountered Bowie just the once. It was in June 1989, in the dressing room of The World, a louche and barely legal downtown Manhattan club. I was there as a journalist, for the first open public performance by his latest project. And I write “encountered” because Bowie declined to answer my questions. Not just some of them but all of them.

That 1989 project was Tin Machine, a group in which Bowie positioned himself as just one individual in the collective. Every question I asked he deflected and pushed sideways to guitarist Reeves Gabrels or the Sales brothers rhythm section – all of whom were, like Bowie, dressed in tight black suits. He was acting out the teenage boy’s dream of pop group as gang, a band of brothers. It was, of course, a fantasy of democracy. To a man, his merry few had nothing of interest to say.

In its own way, it was another Bowie persona. And one that, according to him, revitalised his career. And maybe facilitated his reintegration of all those cracked actors into one, happier self. But, contrarily, Oliver says, “There is simply no explanation for the change in Bowie. No one knows or if they do they are not talking.”

One last thing. Oliver’s email address. It has the word ‘ziggie’ in it. It’s not a new address either. He’s had it forever. So, spelling aside, is it a reference to Ziggy Stardust? Is it a clue that in this book, Oliver is working out something of his own? That he tried on the persona of one of Bowie’s personas to reintegrate himself?

The answer is both more prosaic and more interesting. “Our cat, which we inherited, was called Ziggy. I just changed the spelling to ‘ziggie’ for the email.”

'Upping Your Ziggy' by Oliver James (Karnac, £9.99) is published today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments