David Cameron's fatal misjudgement over the EU referendum will leave him dangerously exposed

Inside Westminster: Expectations that the PM would produce a surprise last-minute concession have not materialised

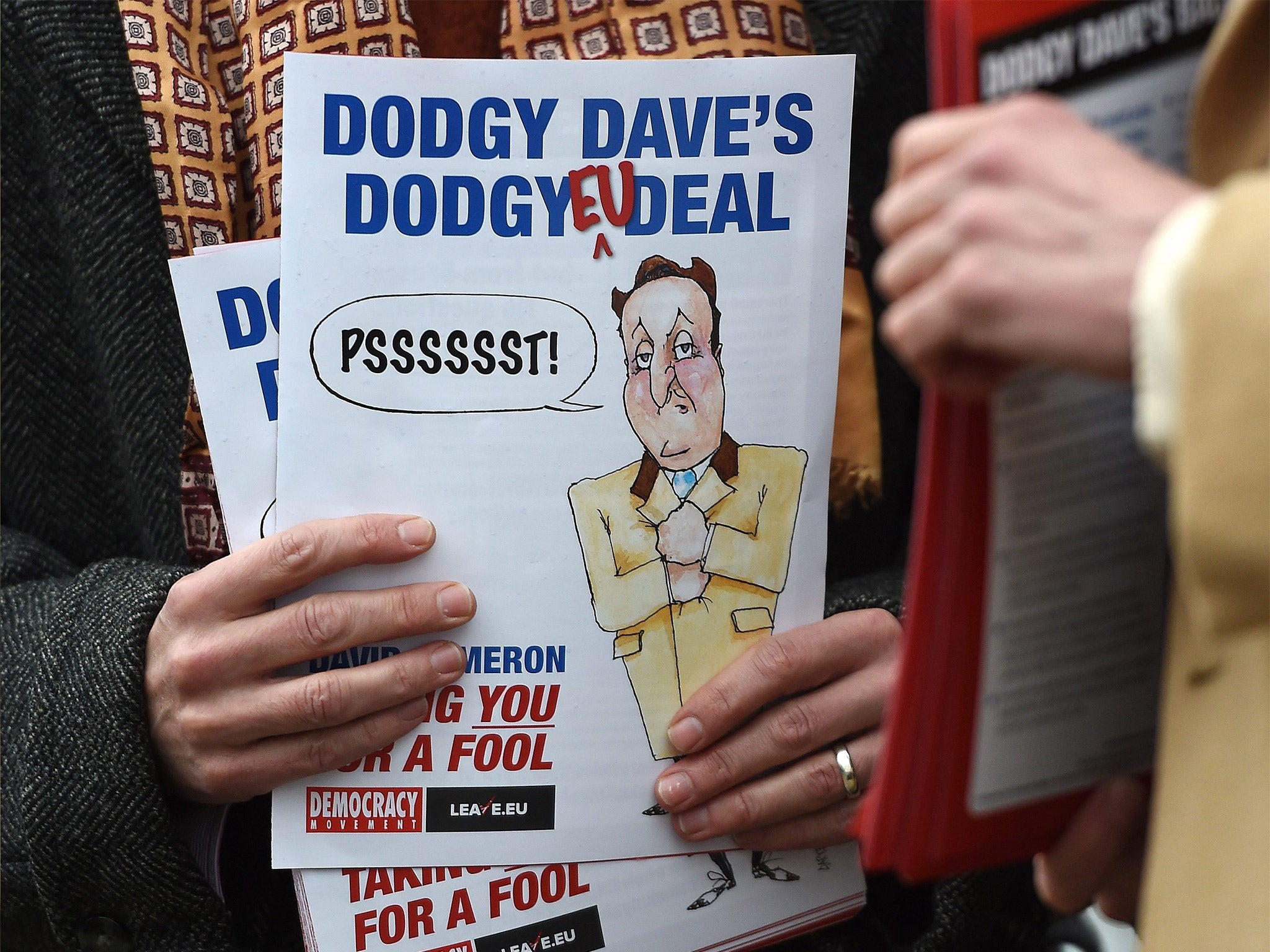

The only rabbit produced at the marathon Brussels summit was Peter Rabbit - in the set of Beatrix Potter books that David Cameron handed to his Belgian counterpart Charles Michel, for his daughter, as part of the Prime Minister’s charm offensive. Previous expectations that Mr Cameron would win a surprise big last-minute concession did not materialise.

Britain’s new deal was not supposed to be as thin as this. In 2013, when Mr Cameron and George Osborne decided to offer an in/out referendum, their strategy was based on their assumption that there would be a “big bang” EU-wide treaty by 2017 to entrench reforms to the eurozone.

It was a potentially fatal misjudgment, which will leave Mr Cameron dangerously exposed when he tries to sell the limited “new settlement” discussed at the summit to the British public. Despite his denials, he would surely have to resign if he loses the coming referendum; he issued the same denial before the 2014 vote on Scottish independence but would have quit if he had lost it.

If there had been an EU-wide treaty negotiation, all 28 members would have tabled their own demands. Britain would have been able to extract a price for allowing the 19 eurozone nations to integrate further. But there was no appetite for treaty change before next year’s French and German elections. Other leaders had no desire to repeat Mr Cameron’s gamble of a referendum with an unpredictable outcome at a time when voters across Europe have moved away from established parties to left or right-wing fringe ones. So seeking a special deal to solve “the British problem” was bound to limit what the UK could achieve.

After Mr Osborne and then Mr Cameron decided it was in the national interest to stay in the EU, they made an important early decision: to ask for what Britain could realistically get in the negotiations, rather than embark on a mission impossible that could lead to an accidental Brexit. A pivotal moment came when some Cabinet ministers, including Michael Gove, pressed for a ceiling on EU migration to the UK. Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, warned Mr Cameron that breaching the EU’s core principle of freedom of movement was a non-runner. In desperation, he grabbed at proposals from the influential Open Europe think tank for a curb on in-work benefits paid to EU migrants. “They didn’t do their homework,” one pro-EU campaigner said. “It was bound to be seen as discrimination against some EU countries.” The strong opposition from the Eastern European nations most affected explains the many battles on the relatively narrow terrain of benefits. Mr Cameron needed a “win” to provide some cover on immigration, which is bound to play a big part in the referendum debate because of the refugee crisis.

The absence of a new EU treaty makes his referendum much more perilous for the Prime Minister. The Outers will claim that the deal is not bankable without a new governing blueprint, as it could be overruled by the European Court of Justice. It means the benefit changes must be approved by the European Parliament, which is giving no guarantees. The public will be less inclined to take the Government on trust than it was in the 1975 EU referendum in which they voted 2-1 in favour of revised membership terms.

Postponing treaty change also undermined Mr Cameron’s mantra that a vote for In is not one for the status quo but to stay in a “reformed EU.” A wholesale negotiation would have considered wider reforms. Whatever the British deal is, it is not the “fundamental, far-reaching change” the Prime Minister promised in 2013. He will now vow to fight for further reforms when the treaty talks finally begin.

Another reason for what Tory Eurosceptics call the “thin gruel” on offer in Brussels was that EU leaders, while wanting to keep Britain inside the EU tent, did not want to encourage other countries to demand a similar special deal. Although genuine disagreements forced the talks to continue into last night, one Brussels insider said: “A lot of it is just theatre for the cameras. This is essentially a commitment to change one EU directive [on benefits].”

Given Mr Cameron’s initial misjudgement, the deal on offer in Brussels is probably as good as he could get. He has worked tirelessly and his defiant body language at the Brussels summit as he “battled for Britain” was designed to underline it. His hyperactive diplomacy -- visiting 20 EU countries, more than any other UK prime minister--was not for show but for hard talking. His need for a special deal meant he had to warm up his rather frosty personal relations with several EU leaders. This marked a U-turn from his decision to veto an EU fiscal pact in 2011, a short-lived victory because 25 EU members went ahead anyway, and which did lasting damage to his relations with them. “He learnt a painful lesson,” smiled one senior British diplomat.

As the deal comes under fire from his opponents, including some Cabinet ministers, Mr Cameron has one reason for hope: most people will not base their vote on the small print of benefit changes or single currency rules, but on the “big picture” of whether Britain is better off in or out of the 28-nation bloc.

The biggest fear in Number 10 is that people who intend to vote to leave will be more motivated to turn out than those who support EU membership on balance, some reluctantly. Somehow, Mr Cameron will have to inspire them.

Cameron loyalists have another private worry. The Prime Minister told the summit that the referendum would settle Britain’s place in Europe “for a generation”. In private, he speaks of 20 years. But the lesson of Scotland is that referendums resolve very little. As one minister who is about to come out as an Outer told me: “I think there will be a narrow vote to stay in. It will settle nothing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks