‘Is it a robot, is it a machine, is it an animal?’: The programable organisms coming to life

There’s a bit of Frankenstein about xenobots, organisms created and programmed by roboticists from the cells of a frog, writes Joshua Sokol. But the uses may change the world we live in; from cleaning up plastics in the sea to targeting cancerous tumours

If the last few decades of progress in artificial intelligence and in molecular biology hooked up, their love child – a class of life unlike anything that has ever lived – might resemble the dark specks doing lazy laps around a petri dish in a laboratory at Tufts University.

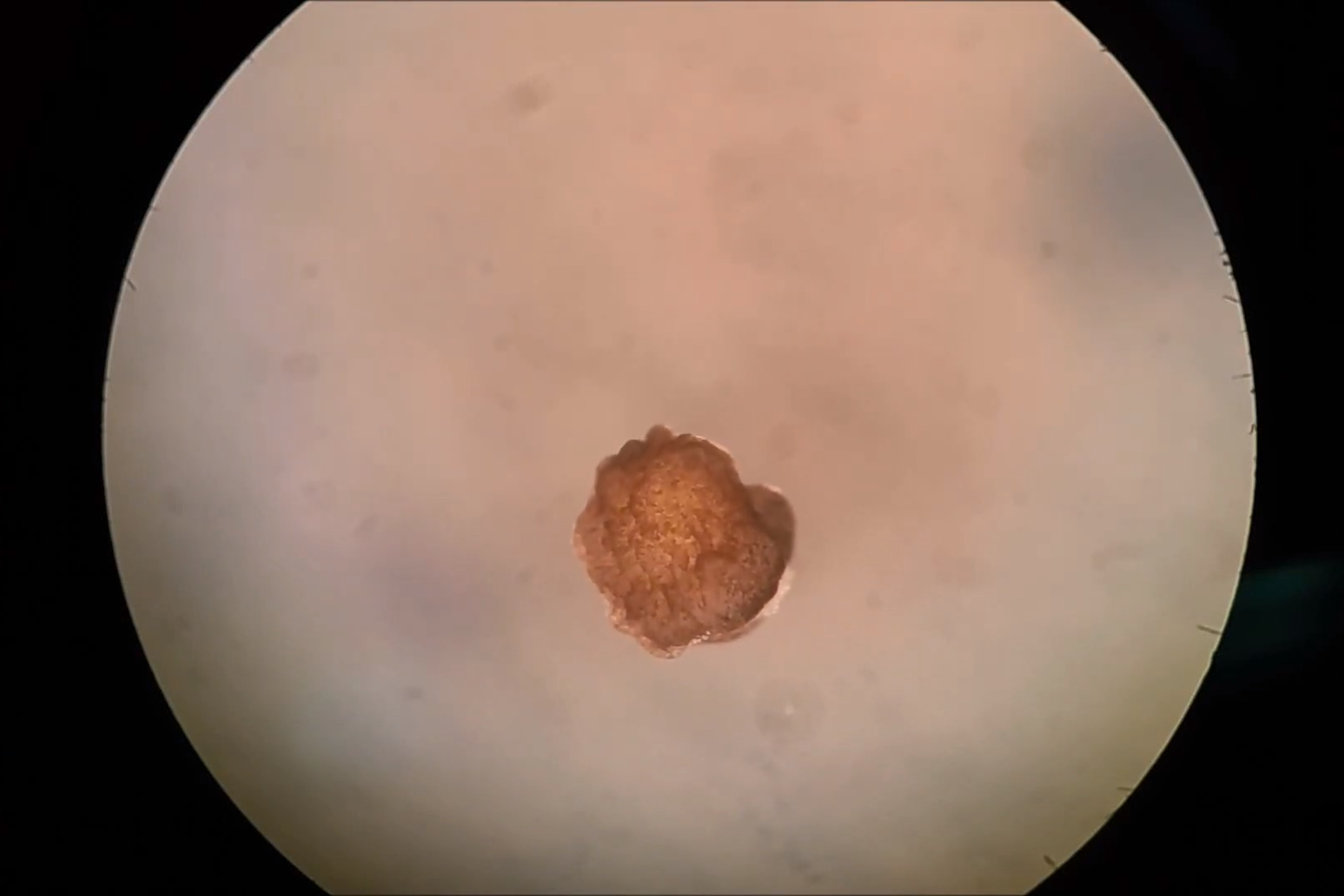

Douglas Blackiston, a biologist, points to one just a little wider than a human hair; squint, and you can just tell it’s moving. But under a microscope, the blob is racing up and to the left. “He’s a lighter –,” Blackiston says, then catches himself. “It’s a lighter colour.”

Strictly speaking, these life-forms do not have sex organs – or stomachs, brains or nervous systems. The one under the microscope consisted of about 2,000 living skin cells taken from a frog embryo. Bigger specimens, albeit still smaller than a millimetre-wide poppy seed, have skin cells and heart muscle cells that will begin pulsating by the end of the day.

These are all programmable organisms called xenobots, the creation of which was revealed in a scientific paper in January. They are named for the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis, which supplies all their cells, and the suggestion, encapsulated in the prefix, that something strange, alien, is at work.

A xenobot lives for only about a week, feeding on the small platelets of yolk that fill each of its cells and would normally fuel embryonic development. Because its building blocks are living cells, the entity can heal from injury, even after being torn almost in half. But what it does during its short life is decreed not by the ineffable frogginess etched into its DNA – which has not been genetically modified – but by its physical shape.

And xenobots come in many shapes, all designed by roboticists in computer simulations, using physics engines similar to those in video games like Fortnite and Minecraft. Xenobots with a fork- or snowplow-like appendage in the front can sweep up loose particles (in a petri dish) overnight, depositing them in a pile. Some use legs, of a sort, to shuffle around on the floor of the dish. Others swim, using beating cilia, or link up blobby appendages and circle each other a few times before heading off in separate directions.

All of which makes xenobots amazing and maybe slightly unsettling – golems dreamed in silicon and then written into flesh. The implications of their existence could spill from artificial intelligence research to fundamental questions in biology and ethics.

“We are witnessing almost the birth of a new discipline of synthetic organisms,” says Hod Lipson, a roboticist at the Columbia University who was not part of the research team. “I don’t know if that’s robotics, or zoology or something else.”

Xenobots are new but not without precedent. Part of their inspiration dates to 1994, when Karl Sims, the computer graphics artist, unveiled some of the world’s first virtual creatures.

Each entered existence in a simulation that approximated real-world physics. Each had a simple task to perform, like battling with another digital creature for control of a cube. And they could evolve over time. Better still, Sims shared a video.

“I saw that, and I knew that’s what I wanted to work on,” says Sam Kriegman, a graduate student who now uses similar virtual simulations to design robots at the University of Vermont, with his adviser, Joshua Bongard.

Most modern AI research focuses on simulated minds inspired by organic brains: neural networks that can beat any human at strategy games, or algorithms that can control pre-designed, occasionally terrifying robot bodies. But a smaller community of researchers, including Kriegman and Bongard, let their simulated robots evolve simple bodies and minds in tandem.

Of course, Sims’ creatures never left their virtual homes. “There was one TV channel that built one just to demonstrate,” he says. But that model was just a blocky replica, not a moving robot.

In their paper and in press coverage, the team hinted at what these xenobots might someday do. Sweep up ocean microplastics into a larger, collectible ball? Deliver drugs to a specific tumor?

In 2000, virtual creatures took a halting first step into the real world when Lipson, then at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, and his colleague Jordan Pollack, a roboticist, connected an algorithm that could evolve its own simple machines to a 3D printer that could make the machines out of plastic.

Still, Kriegman and Bongard doubted that some of their own designs could ever emerge out of a computer. Then they started working on a project for Darpa, the futuristic research wing of the US Department of Defence, with Blackiston and Michael Levin, a biologist who directs the Allen Discovery Centre at Tufts.

In one Skype call between groups, Kriegman showed a video of one of his virtual creatures. It looked like a squat table and walked by rocking between its front and back legs.

“They said, ‘There’s no technology currently in existence to build something like this,’” Blackiston recalls. But to him, the creature looked like something far simpler: a clump of cells. “I said, ‘I bet we could build this,’ and I think there was some audible laughter.”

Blackiston got to work. He began with fertilised frog eggs, then pried them open and gathered skin cells from the embryo inside each one. Developmentally, these cells were fated to sit on the surface of a tadpole and ward off pathogens; now they would do something else.

Next, Blackiston swept the skin cells into a little well, forming a milky ball. Soon the cells glued themselves back together. Then he cauterised away some parts of the ball, carving a tiny figurine – a living skin-sculpture, about the size of a fine grain of salt, that looked like Kriegman’s quadruped. Two weeks later, he showed a picture of the entity to the Vermont computer scientists.

“We were just dumbfounded,” Bongard says. “The moment we saw that, both labs really just kind of dove into this full time.”

In Vermont, he and Kriegman began crafting virtual worlds that would reward particular behaviours by the clumps of repurposed frog. Take walking: first an algorithm produced many random body designs; some just sat there, others rocked or waddled forward. Then the algorithm let the best of the walkers procreate into the next generation; from these, another generation was produced, and so on, each one improving on the best designs. Another simulation, aimed at finding designs that could carry an object, became crowded with bagel-like bodies that had evolved a central cavity to hold things.

After the process ran for about a day, it produced body shapes pre-programmed to execute the initial tasks. Then the Vermont team relayed the resulting best body shapes to Levin and Blackiston, who began trying to sculpt cellular figurines that resembled those designs: First with just skin cells, then also with cardiac tissue – an assemblage of muscle cells that contracts and expands. The Tufts team offered feedback, to make the next round of simulations better at predicting what would happen in a real petri dish. And so on, in a loop.

Of greater concern, they said, was how xenobot toxicity, life span and the hypothetical ability to someday reproduce would be assessed and regulated. ‘Applied ethicists should be involved in their creation and development’

In their paper and in press coverage, the team hinted at what these xenobots might someday do. Sweep up ocean microplastics into a larger, collectible ball? Deliver drugs to a specific tumour? Scrape plaque from the walls of our arteries? The xenobots would biodegrade after using up the yolk inside their cells. And whatever their intended purpose, their bodies would be designed not by an engineer but by a simulacrum of real evolution built to encourage the right behaviour in the target environment.

“What should a robot look like that’s crawling through your arteries?” Kriegman says. “Should it have four legs? I don’t know!”

“It’s so compelling to even start imagining things at that scale, to open that door for our imaginations,” says Christina Agapakis, a synthetic biologist in Boston who did not participate in the research. “Well, what if your machine was alive? And biodegradable? And programmable?”

None of the researchers wanted to forecast when such applications might come to pass. Blackiston can try out as many as 50 computer-suggested designs in a week, but is considering how the process might be automated with 3D cell printers.

At the lab, Levin and Blackiston emphasises that they are more interested in using xenobots as experimental tools to uncover basic biological principles, and philosophical ones, too. “People will ask: Is it a robot, is it a machine, is it an animal?” Levin says. “What this is really telling us is that we need to have better definitions of all these things.”

In the meantime, outside ethicists have begun to weigh in. “An uneducated public may see this as Frankenstein-like,” wrote Susan and Michael Anderson, a husband-and-wife team affiliated, respectively, with the University of Connecticut and the University of Hartford, who specialise in machine ethics, in an email. Of greater concern, they said, was how xenobot toxicity, lifespan and the hypothetical ability to someday reproduce would be assessed and regulated. “Applied ethicists should be involved in their creation and development, not just scientists and engineers,” they wrote.

Levin stresses that he regularly consults with an ethicist at Harvard’s Wyss Institute, and points out that research using animals like frogs – or their embryos – already falls under ethical oversight. At the moment, other living, adaptive systems like treatment-resistant bacteria are more advanced and dangerous than xenobots. “To be worried about xenobots, in a world where we already have both natural and human-designed pathogens, is just nuts,” he says.

The team’s published paper is only the first entry in a series of studies. Future work will explore how these organisms behave with computer designs and as unsculpted balls of cells.

“It’s exciting because of what it makes you think about, extrapolating into the future,” Sims, the virtual creatures pioneer, says after looking at the team’s videos of xenobots. “It’s kind of fun when they feel alive.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks