Quantum computers: Prospect of faster, more powerful machines a step closer after 'game-changing' breakthrough

Scientists have developed the central element of practical quantum computer that could transform the digital landscape

The prospect of quantum computers that are many times faster and more powerful than existing machines has come a step closer with a “game changing” breakthrough in the development of silicon chips based on the weird principles of quantum physics.

Scientists in Australia have demonstrated the central element of a practical quantum computer that could transform the digital landscape with super-fast and intelligent microprocessors for the electronic devices of the future.

The researchers have built a logic gate – the logically controlled switches that allow calculations to be made – that operates on the principles of quantum physics, where something can exist in two states at the same time.

In classical computing, data is composed of binary digits which are always represented in one of two states, either “0” or “1”. However, quantum computers harness the strange behaviour of very small particles such as electrons which can exist in two states at once, due to quantum process known as superimposition, so that data is held as quantum bits or “qubits”.

Until now it has not been possible to make two qubits talk to one another in a logic gate, but a team led by Andrew Dzurak of the University of New South Wales in Sydney has now achieved the feat in a study published in the journal Nature.

“We’ve demonstrated a two-qubit logic gate – the central building block of a quantum computer – and significantly done it in silicon,” Professor Dzurak said.

“Because we use essentially the same device technology as existing computer chips, we believe it will be much easier to manufacture a full-scale processor chip than for any of the leading designs, which rely on more exotic technologies,” he said.

“This makes the building of a quantum computer much more feasible, since it is based on the same manufacturing technology as today's computer industry. If quantum computers are to become reality, the ability to conduct one and two-qubit calculations are essential,” he added.

On a physical level, bits are typically stored on a pair of silicon transistors, one of which is switched on while the other is off.

In the quantum computer data is encoded in the “spin”, or magnetic orientation, of individual electrons. Not only can they be in one of two “up” or “down” spin states, but also a superposition of up and down.

The key step taken by the Australian scientists was to reconfigure traditional transistors so that they can work with qubits instead of bits.

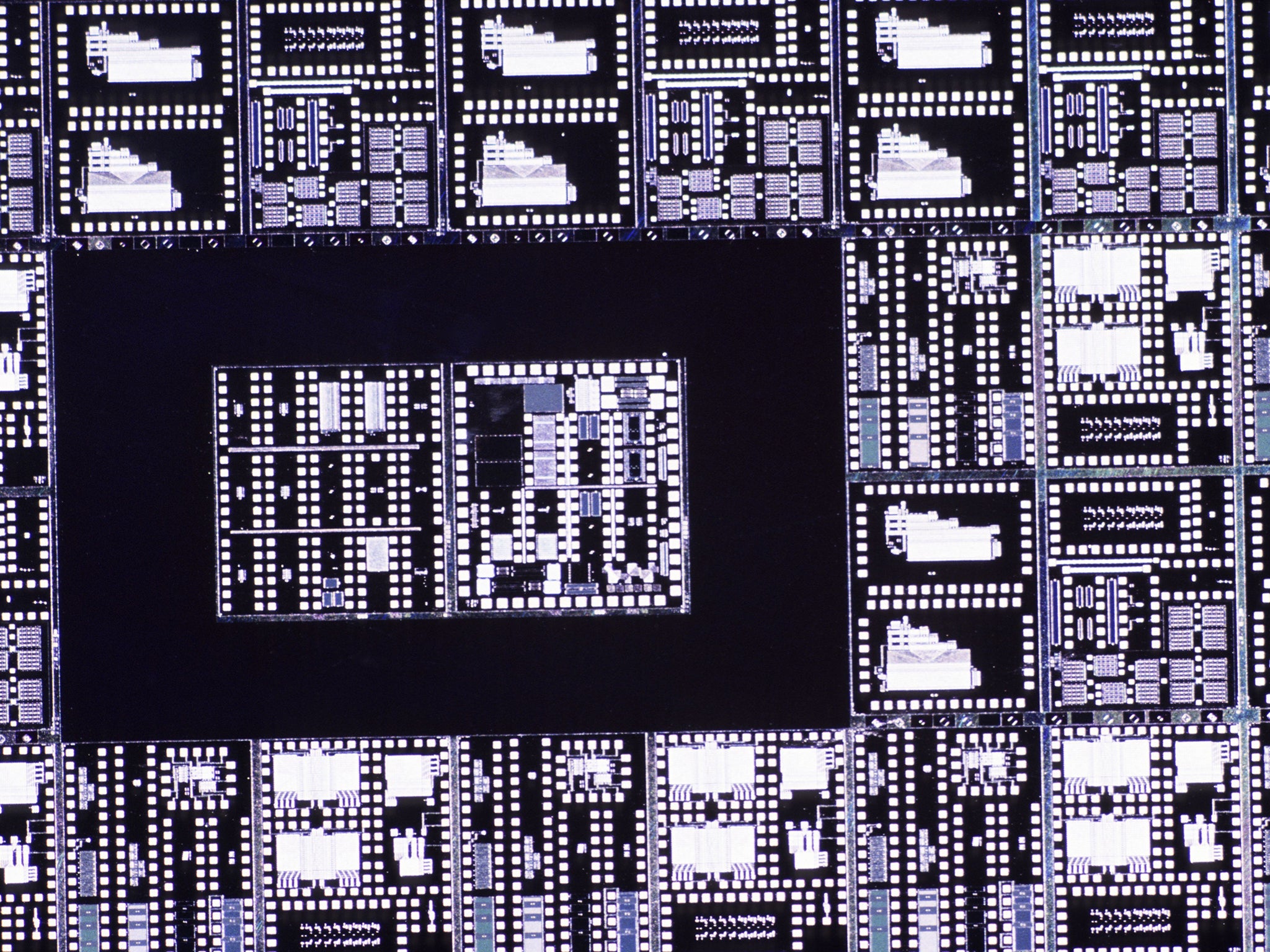

Lead author Dr Menno Veldhorst, also from the University of New South Wales, said: “The silicon chip in your smartphone or tablet already has around one billion transistors on it, with each transistor less than 100 billionths of a metre in size.

“We've morphed those silicon transistors into quantum bits by ensuring that each has only one electron associated with it. We then store the binary code of 0 or 1 on the 'spin' of the electron, which is associated with the electron's tiny magnetic field.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks