Duolingo: The future of language learning that puts a personal tutor in everyone's pocket

Seth Stevenson tries out the new app that everyone's talking about, which won't even cost you a penny – or a peso

In mid-December, Apple named Duolingo – a piece of language-learning software – its 2013 iPhone app of the year. Since then, I swear every native English speaker of my acquaintance has suddenly begun guten tag-ing, buongiorno-ing, and comment ça va-ing.

I myself have been habla-ing Español for the past three weeks, with Duolingo as my guide. Verdict so far? ¡Excelente, mis amigos! Until we genetically engineer the Babel fish that Douglas Adams envisioned in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Duolingo may be our best bet for a global increase in inter-lingual understanding.

The app currently teaches Spanish, French, Italian, German, and Portuguese to English speakers, and teaches English to speakers of those languages plus Dutch, Russian, Hungarian, and Turkish, with more on the way.

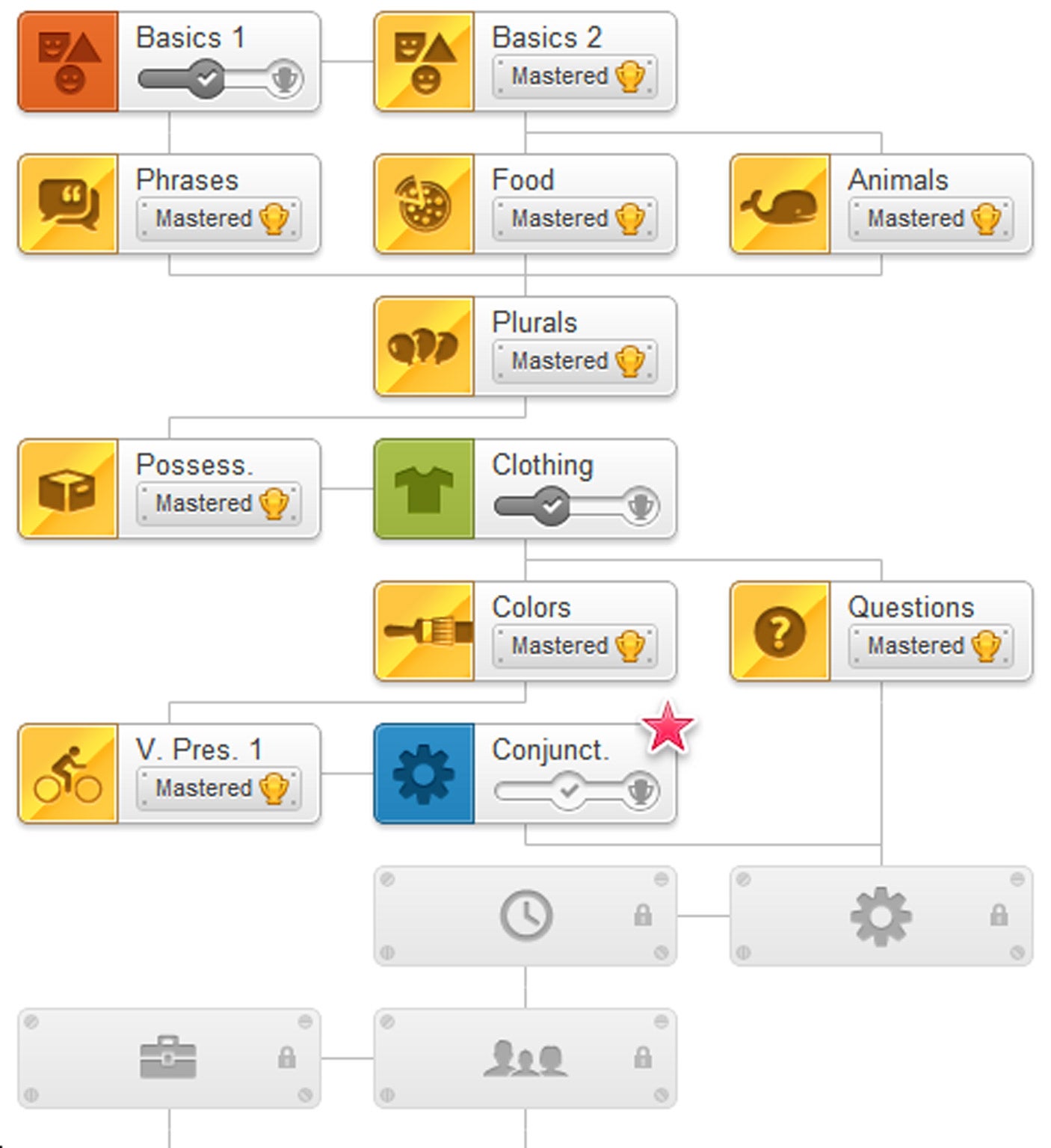

As with all else that manages to hold the attention of post-millennials – Foursquare, Instagram – the key to Duolingo's success lies in gamification. Whether it's vying to become the virtual mayor of a pub or racking up likes for our holiday photos, we clearly enjoy turning the stuff of life into bite-sized, recreational competitions. Duolingo recognises that humans are wired this way. It also recognises that the key to learning a new tongue is repetition. So the app transforms language study into an amusing diversion, complete with points, leaderboards, and video game "lives". At the end of each successfully completed round, we're rewarded with a trumpet fanfare and a delicious sense of accomplishment.

This is the most productive means of procrastination I've ever discovered. The short lesson blocks are painless and peppy, and reaching the next level (and then the level after that) becomes addictive. I've lost track of time as I've buzzed through tutorials on Spanish conjunctions and prepositions. A co-worker likes to crank out French modules on his train to work. One friend confided that she's stayed up for hours past her bedtime learning German – ja, this fräulein simply can't put Duolingo down. As I recall, these are not the sorts of giddy emotions that were stirred in French lessons at school.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Duolingo: it doesn't cost anything. It's free to download and, according to its 34-year-old co-founder Luis von Ahn, it will be free for ever. When von Ahn gushes about his creation, he's less excited by the idea of yuppie professionals in the UK and US brushing up on their Italian and more enthusiastic about people in Latin America attempting to improve their socioeconomic status.

"The majority of people in the world who want to learn a language are learning English because it might get them a better job," says von Ahn. "And learning a language usually requires money. You need to attend a good school that has a foreign languages department, or buy a program like Rosetta Stone that can cost hundreds of pounds." Von Ahn himself grew up in Guatemala, but went to a school with English classes. "I was one of the wealthy few," he says. He went to the United States to attend college and graduate school, then went on to become a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon and eventually a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship.

If it doesn't charge users and, so far, doesn't serve them any ads, how does Duolingo make money? It tricks you into working as an unpaid translation service. At the end of some lessons, Duolingo will ask you if you want to practise by translating a real-world document. Which will turn out to be, say, a BuzzFeed article. By melding together enough stabs at this task from high-level Duolingo users, the app can render a surprisingly accurate translation. Which is worth good money. So far, Duolingo has contracts with BuzzFeed and CNN to translate stories from English into languages such as Spanish, French, and Portuguese. This service is already earning Duolingo hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, but von Ahn predicts he will be adding a raft of new clients soon. "The language translations market is huge," he says. "It's a £15bn per year market."

This nifty scheme – transforming your users into unpaid, joyful labourers – isn't new for von Ahn. He previously worked on the Captcha system, which you may know as that annoying thing that makes you type in your interpretation of blurry, warped text to prove you're not a bot every time you want to buy concert tickets. Captcha led to reCaptcha, which was bought by Google and is a fiendishly clever bit of stealth crowdsourcing. Instead of asking you to interpret just one block of blurry text, reCaptcha makes you do two. One is to prove you're human. The other is a scrap of a scanned page from an old print newspaper article or book. By forcing users to type the text they see, Google has managed to digitise reams of content for its own library.

Projects such as these require huge numbers of participants, and Duolingo already has them. According to von Ahn, being named app of the year took Duolingo from 16 million to 20 million users in the space of a week. He says the app now draws more than 100,000 new users each day. Which not only keeps the translation service humming, but also helps the app learn how to teach languages better.

on Ahn says he could find no satisfying data demonstrating the most effective method for teaching languages, so he A/B tests various methods in the app to see what works best. "If we want to know whether to teach adjectives or plurals first," he says, "we do an A/B test set, measure which does better, and then start using the winning method for all users. In doing that, we've already modified our teaching methods quite a bit."

For instance, when teaching English to Spanish speakers, Duolingo starts with personal pronouns. But von Ahn discovered that, because Spanish does not use the pronoun "it" in sentences such as "It is snowing outside," novice students were baffled. "We learnt from A/B testing that a lot of people were failing right there when we introduced it, so we started teaching it later. Anything super confusing when you're just starting makes people give up."

The teaching style you'll encounter in Duolingo is quick, upbeat, and forgiving. It rarely explains the grammatical logic behind a new concept. It just throws you into the pool and, when you can't swim, scoops you up and throws you in again – until you find to your amazement that you can suddenly float on your own. Like Rosetta Stone, Duolingo associates photos with nouns to aid your memory. Unlike those secondary-school French lesson, it does not force you to conjugate verbs with rote recitations.

Some learners may miss that sort of traditional pedagogy. (You can find it in an app such as Babbel, which makes you go through the je suis, vous êtes, nous sommes litanies – but charges you each month for the privilege.) Duolingo also isn't designed to drill you in "Where is the railway station?"-type phrases in preparation for your trip to Paris next week. It's meant to transform you over the course of months into a well-rounded conversationalist.

According to von Ahn, reaching the current goal for the app is to help you achieve roughly the B2 level ("upper intermediate user") in the common European framework of reference for languages. "You won't sound native," he says, "and when you're talking you'll do a lot of simplifications. You'll probably mess up the subjunctive form. But you'll get around. You'll understand what you hear very well. You'll be able to read books and watch movies in the language."

Reason enough for me. And now I have to go – I need to level up a few more times so I can screen myself an Almodóvar marathon. ¡Hasta pronto!

A version of this article appeared on Slate.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks