First brain-to-brain interface to communicate using only your mind successfully tested, researchers claim

'We essentially "trick'" the neurons in the back of the brain to spread around the message that they have received signals from the eyes,' one researcher explains

Researchers claim to have developed a way for three people to communicate and solve problems together using only their brains.

The BrainNet system, built by a team at the University of Washington, s the first brain-to-brain network of its kind and is a major advancement towards realising telepathic communication, the researchers claim.

It is the first time a person has been able to both send and receive information using only their mind, as well as the first system to involve more than two people, the researchers say.

"Humans are social beings who communicate with each other to cooperate and solve problems that none of us can solve on our own," said Rajesh Rao, a professor at the University of Washington's Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering.

"We wanted to know if a group of people could collaborate using only their brains. That's how we came up with the idea of BrainNet: where two people help a third person solve a task."

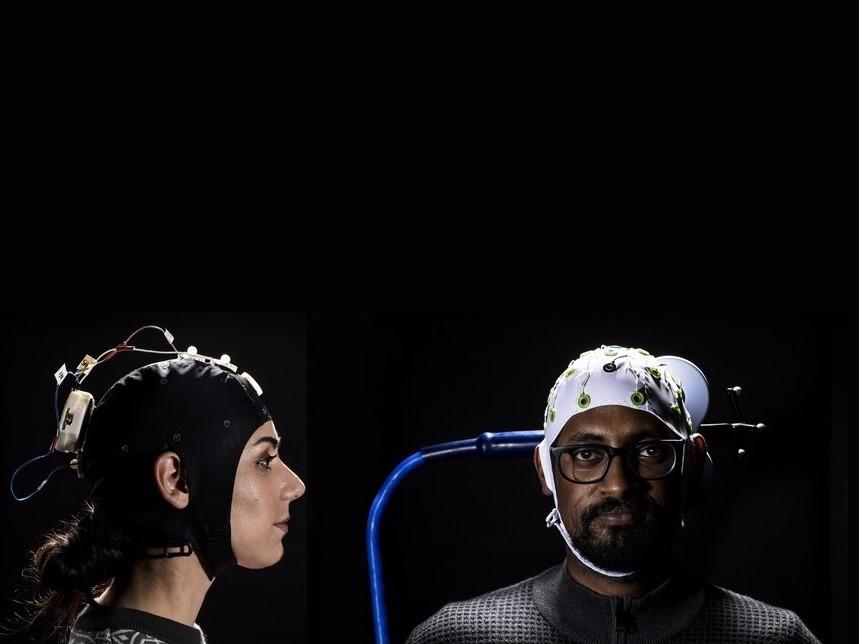

The research, published in April in Scientific Reports but only just publicised by the university, involved two people helping a third person to solve a task using inter-connected head gear.

Experiments involved a Tetris-like game, where two people, referred to as 'senders', could see the game but not control it.

The third person, or 'receiver', could only see one part of the game and had to rely on the two senders to transmit the remaining information through the BrainNet interface in order to successfully complete the game.

All three participants in the experiment were in different rooms and unable to see, hear, or speak to one another.

"To deliver the message to the receiver, we used a cable that sends with a wand that looks like a tiny racket behind the receiver's head. This coil stimulates the part of the brain that translates signals from the eyes," said co-author Andrea Stocco.

"We essentially 'trick' the neurons in the back of the brain to spread around the message that they have received signals from the eyes. Then participants have the sensation that bright arcs or objects suddenly appear in front of their eyes."

The researchers hope that the technology will develop sufficiently so that in the future teams of inter-connected brains will be able to work together to solve problems that one brain by itself could not solve.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments