Stargazing for September 2017: suicide of a spaceprobe

As Cassini nears its end after 13 years with the ringed planet, what can we expect in the skies this month?

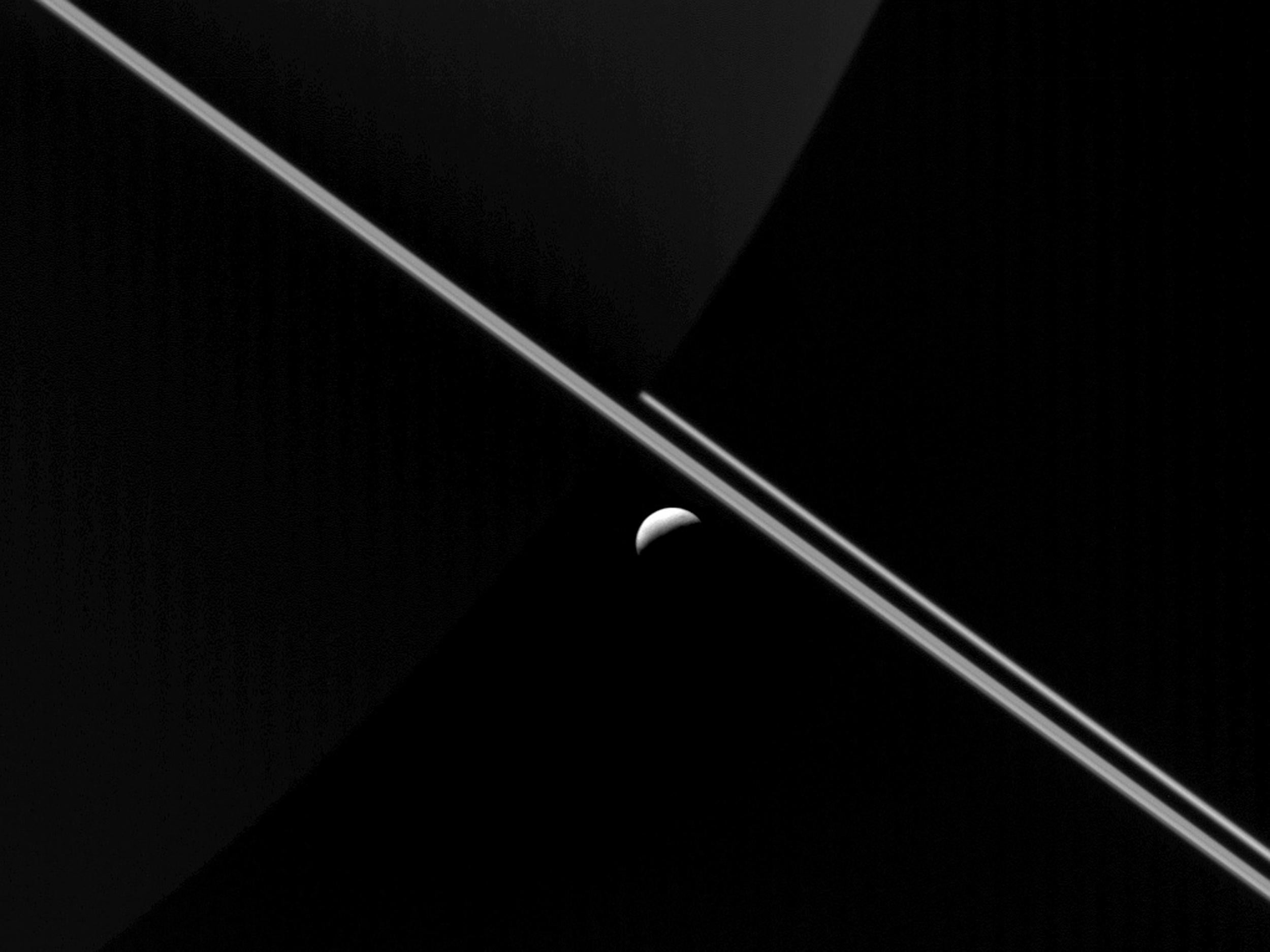

On 15 September, the spaceprobe Cassini will self-destruct in the clouds of Saturn. It has been a constant companion of the giant ring world since 2004, orbiting the planet and surveying its family of 62 moons.

If you want to see Saturn for yourself, look low in the southwest. It’s an unspectacular, yellowish ‘star’ – but try gazing at it through even the smallest of telescopes. It looks artificial, like a “Boys’ Own” vision of a planet. Believe us, it’s an incredible sight.

The Cassini mission was the brainchild of NASA and ESA (the European Space Agency). Named after Domenico Cassini – a seventeenth-century French/Italian astronomer who discovered the main division in Saturn’s rings – it piggybacked Europe’s Huygens craft to Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan (first spotted by a contemporary of Cassini, Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens).

Titan is an enigma. One of the biggest moons in the solar system, it’s cloaked in a dense orange atmosphere of nitrogen, whose pressure is 1.5 times that of the Earth’s air. In 2005, Huygens separated from Cassini and audaciously parachuted down to the surface of Titan. It landed on a world covered in lakes of organic compounds – methane and ethane – one of which is larger than any of the Great Lakes of America. This iconic world has the right chemistry to develop life.

And so has Enceladus, another of Saturn’s moons. Cassini discovered that it has geysers made of water ice, spewed up from an underground ocean. A NASA spokesperson acknowledged: “It’s the most likely place in the solar system to host alien microbial life”.

Saturn itself came up with surprises. In 2006, its south pole developed an enormous hurricane, 8000 kilometres across. It boasted wind speeds of nearly 600 km/hr.

Not to be outdone, the planet’s northern hemisphere fought back in 2010. It hosted the “Great White Spot”: an enormous storm in Saturn’s normally bland atmosphere. These spots, which appear periodically, can be thousands of kilometres across.

Cassini’s mission has been extended year after year – but all good things must come to an end. NASA engineers have been progressively decelerating the orbiting spacecraft with a series of weekly dives between the gaps in the rings, and Saturn itself. The grand finale of the mission will yield close-up data about the ring world as never before.

Why kill Cassini? Scientists have gathered enough information that makes them convinced that two of Saturn’s moons – Titan and Enceladus – could harbour life in the future, when our ageing sun grows to become a red giant. They can’t risk Cassini remaining in orbit: were it to collide with either moon, it would wreak devastating biological contamination.

So: farewell, Cassini. In Bruce Forsyth’s words: didn’t he do well?

What’s up?

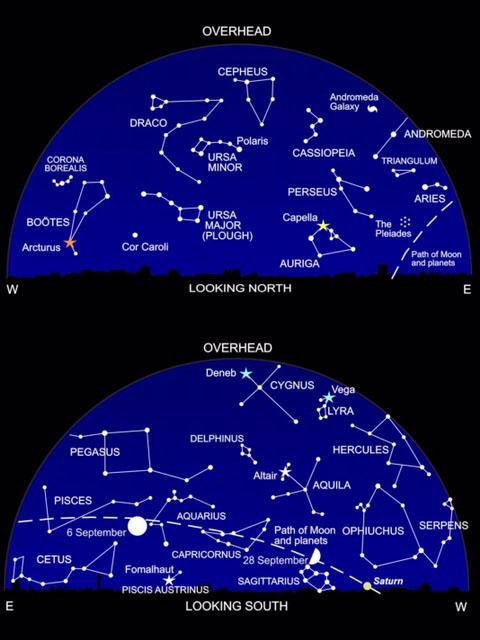

Say goodbye to Jupiter this month: after dominating the evening sky all summer, the giant planet is on its way out. Early in September you can catch Jupiter low in the west after sunset, but by the end of the month it will have slipped down into the twilight glow.

Saturn is still holding the planetary fort, low in the southwest. It’s a bright jewel below the dim stars of Ophiuchus: the Serpent-Bearer.

Look overhead for the much brighter stars Vega and Deneb, swimming in the Milky Way: together with Altair, in the south, they make up the great Summer Triangle. To the upper left of Altair lies a small but perfectly formed constellation: Delphinus, the Dolphin, with his trapezoidal body and tiny tail.

If you want some real action, though, you’ll have to be up with the lark. Brilliant Venus rises about 3.30, blazing as the glorious Morning Star. With binoculars, check out Venus on the first couple of nights of September, and you’ll spot a pretty little cluster of stars nearby. This is Praesepe: scan it through a telescope and you can see why it’s nicknamed the Beehive Cluster.

During the first half of September, watch two planets performing some deft choreography with a star, low in the eastern dawn twilight. The stationary partner is Regulus, the brightest star in Leo (the Lion). At the beginning of September, you’ll find Mars nearby: it’s about the same brightness as Regulus, but you’ll notice its distinct orange colour. Slightly brighter Mercury lies to the right.

As the mornings go by, Mars and Mercury move down to the left, leaving Regulus behind as they move together for a close planetary canoodle on the mornings of 16 and 17 September.

Diary

6 September, 8.03 am Full Moon

12 September Mercury at greatest western elongation

13 September, 7.25 am Moon at Last Quarter

20 September, 6.30 am New Moon

28 September, 3.54 am Moon at First Quarter

For a preview of all that’s up in the sky next year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book: Philip’s 2018 Stargazing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks