Scientists finally understand the strange behaviour of meteorites as they fall to Earth

The most protected part of the meteorite is usually its rear

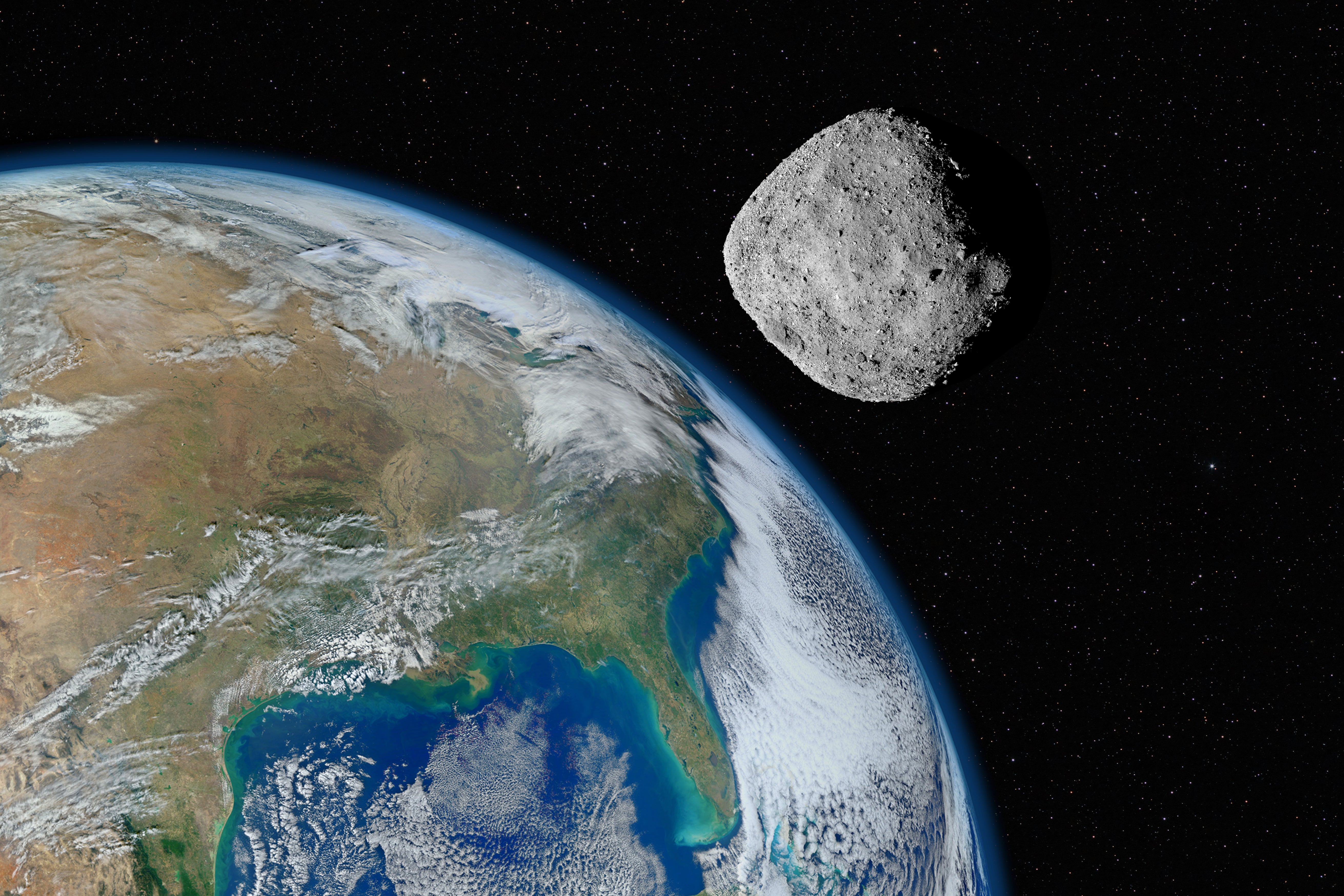

Scientists have worked out why rocks survive crashing to the Earth’s surface as meteorites, despite the brutal heating they go through.

"Most of our meteorites fall from rocks the size of grapefruits to small cars," said lead author and meteor astronomer Peter Jenniskens of the SETI Institute and Nasa Ames Research Center.

"Rocks that big do not spin fast enough to spread the heat during the brief meteor phase, and we now have evidence that the backside survives to the ground."

Researchers unlocked this secret with the help of 2008 TC3, a 6-meter-sized asteroid that was detected in 2008 and which scientists tracked for over 20 hours before it hit the Earth’s atmosphere, creating a bright meteor that disintegrated over the Nubian Desert of Sudan – resulting in a shower of meteorites.

"In a series of dedicated search campaigns, our students recovered over 600 meteorites, some as big as a fist, but most no bigger than a thumbnail," says University of Khartoum professor Muawia Shaddad. "For each meteorite, we recorded the find location."

The researchers were surprised to find that the larger fist-sized meteorites were spread out more than the smaller meteorites.

Models of 2008 TC3 showed how the asteroid melts and breaks up, suggesting that the asteroid punched a near vacuum wake in the atmosphere. The first fragments came away from the side of the asteroid, falling at a relatively low speed.

When the smallest meteorites fall to Earth, friction in the atmosphere stopped them from reaching the surface while larger asteroids survived the trip.

"The asteroid melted more and more at the front until the surviving part at the back and bottom-back of the asteroid reached a point where it suddenly collapsed and broke into many pieces," said Mr Robertson. "The bottom-back surviving as long as it did was because of the shape of the asteroid."

Dr Jenniskens added: "The largest meteorites from 2008 TC3 were spread wider than the small ones, which means that they originated from this final collapse. Based on where they were found, we concluded that these pieces stayed relatively large all the way to the ground."

The different meteorite types were spread randomly on the ground, but scientists know that cosmic rays in space can creator a low-level activity – especially on a meteorite’s surface.

"From that radioactivity, we often find that the meteorites did not come from the better-shielded interior," said Dr Jenniskens. "We now know they came from the surface at the back of the asteroid."

The research was published in Meteoritics and Planetary Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks