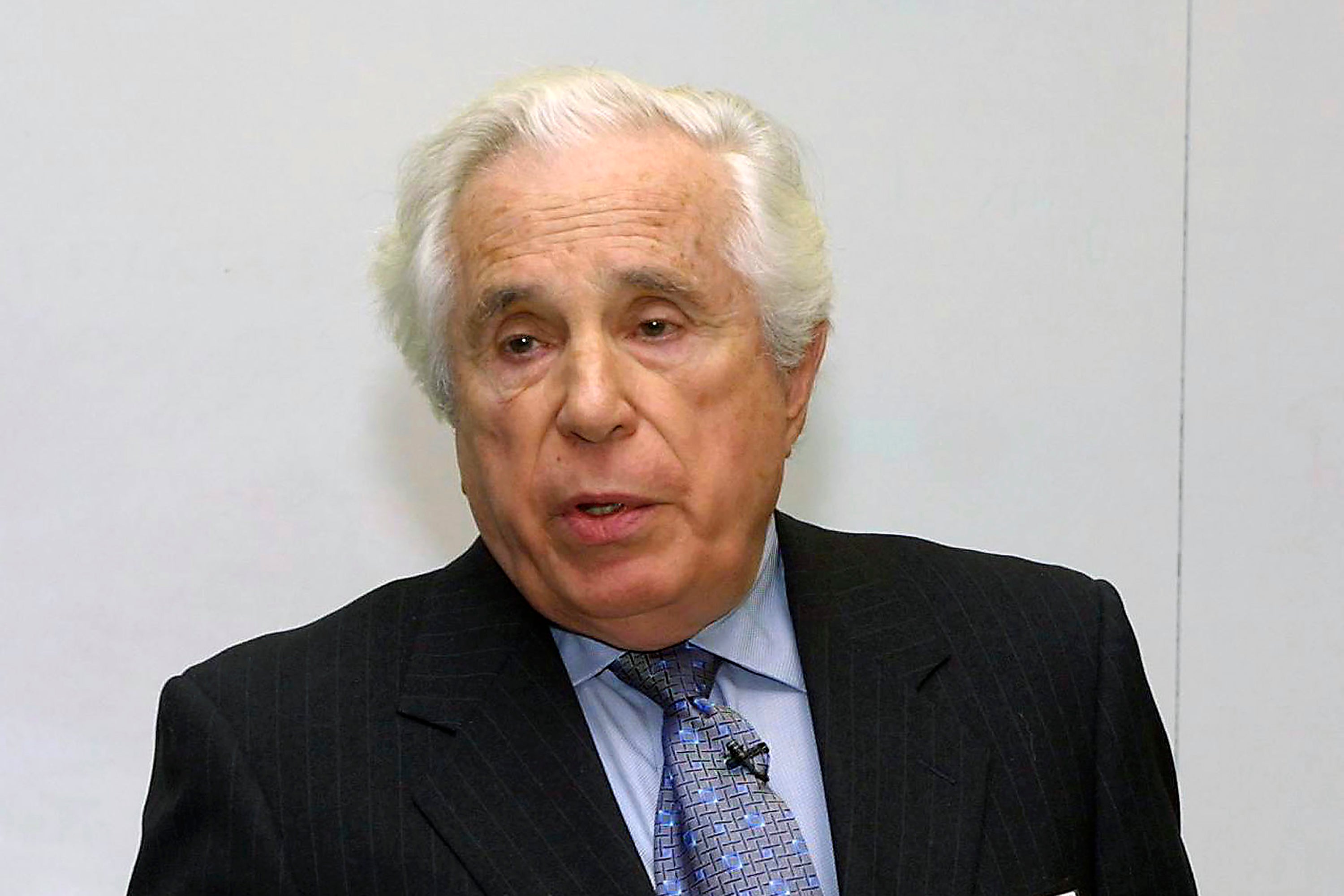

Renowned world correspondent Seymour Topping dead at 99

One of the most accomplished foreign correspondents of his generation has died

Seymour Topping, among the most accomplished foreign correspondents of his generation for The Associated Press and the New York Times and later a top editor at the Times and administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, died on Sunday. He was 99.

Topping passed away peacefully at White Plains Hospital, his daughter Rebecca said in an emailed statement.

As a correspondent for the AP in 1949, he was eyewitness to the fall of Nanking, then the capital of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government, to Mao Zedong’s Red Army. It was the key victory in the Communist conquest of China and Topping was first to report it to the world.

After the Communists consolidated their hold and publicly aligned with Soviet leader Josef Stalin Topping and other American correspondents were ousted from the mainland, with Topping arriving in Hong Kong in late 1949. From there, after a home leave visit to the United States and an urgent detour to Canada to visit and marry his future wife, Audrey, he returned to the AP bureau in Hong Kong.

He was hoping that the Chinese Communist authorities would agree to his request to go back to China. While awaiting their answer, Topping accepted an assignment in French Indochina.

As he recounted it in a 1972 memoir of his reporting career in Asia, “Journey Between Two Chinas,” the AP wanted him to “go to a funny little country whose name was sometimes mixed up by our editors in New York with Indonesia. It was Indochina. There was some kind of trouble in Vietnam, and would I go there for a month?” He and Audrey had just checked into the Continental Hotel in Saigon in February 1950 when a plastic bomb thrown by a cycle driver ripped through a café across the square, shaking the hotel. He rushed out to a scene of chaos.

“French soldiers and sailors, dead and wounded, lay amid overturned tables and shattered glass inside the café and outside on the sidewalk terrace where they had been sipping drinks,” he wrote. “The war was on in the South in full fury.”

Over the next two years, Topping wrote presciently about the strength of the insurgency against the French colonial occupiers of Indochina and the long and bloody struggle that would continue almost without interruption until the final U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975.

After postings to London as diplomatic correspondent and West Berlin as bureau chief for the AP, Topping in 1959 joined the Times, where he was to work for the next 34 years.

Known as “Top,” he was chief correspondent in Moscow and Southeast Asia, foreign editor, assistant managing editor, deputy managing editor and finally managing editor under Times Executive Editor A.M. Rosenthal for 10 years from 1977 to 1987. He became director of editorial development for the New York Times newspaper group until his retirement in 1993 from the company.

For the next decade, he served as administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes at Columbia University and simultaneously held the San Paolo Professor of International Journalism Chair at Columbia Journalism School.

“As the longstanding dean of the Pulitzer Prizes, Seymour Topping set the highest standard of excellence and integrity for judging and awarding the prizes in journalism and arts and letters,” said Dana R. Canedy, the current prize administrator. “His vision and leadership as Pulitzer administrator have withstood the test of time and continue to influence the prize awarding process.”

He stopped teaching in 2002. He remained engaged in writing and in international affairs and journalism as a member of the International Press Institute and the Council of Foreign Relations, among other organizations, and was a frequent attendee at events at the AP and the Overseas Press Club well into his 90s.

Born Dec. 11, 1921, in Harlem, New York, Topping was the son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. He wrote that he developed a fascination with China at a young age and decided at 16 as a high school editor that he wanted to become a newspaper correspondent there.

That led him to enroll at the University of Missouri, whose journalism school had connections to China and the Far East, and he graduated in 1943. After serving as a U.S. infantry soldier in the Pacific in World War II, Topping demobilized in the Philippines and began to put his journalist training to work in 1946, first as a part-time stringer and then as a staff reporter in Asia for the International News Service.

From there, he was sent to China and landed a better-paying job with the AP in Shanghai in 1948. Topping covered the pivotal battle of Huai-Hai and then remained in Nanking as diplomats and Nationalist government officials and troops fled the oncoming Red Army.

Topping was there when Mao’s forces swept in the night of April 24 and clandestine Communists emerged in the open to seize control of the city. An Agence France-Presse reporter with Topping won a coin toss to telegraph word to his editors first, Topping recalled, but Paris editors held onto his colleague’s three-word flash, awaiting details.

Instead, Topping’s longer dispatch went out immediately on the AP’s wires, after which lines from the city were cut. He had achieved a world beat on the story.

Topping met Audrey Rodding, who became his wife and collaborator of 69 years, in 1948 while she was an 18-year-old student at the University of Nanking. She was the daughter of Canadian diplomat Chester A. Ronning and was from a family of Lutheran missionaries in China.

While a reporter and then an editor at the Times, Topping was frustrated that he had never been able to return to China. The United States had never recognized the People’s Republic of China, which in turn would not admit journalists from the United States throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Topping’s chance finally came in 1971 in the wake of the “pingpong diplomacy” between the United States and China.

Topping had met Chou En-lai during the Chinese civil war. In 1971, Audrey, then working as a freelance photographer and writer while accompanying her father on a diplomatic mission to China, sent word that Chou had agreed to invite Topping back.

“How I had longed these many years to see again the panorama of villages, the tile-roof dwellings ... and the cities surging with the torrential energies of a people unlike any other,” he wrote in the prologue of “Journey Between Two Chinas.”

Besides “Journey Between Two Chinas,” published in 1972, Topping authored “On the Front Lines of the Cold War: An American Correspondent’s Journal from the Chinese Civil War to the Cuban Missile Christ and Vietnam,” published in 2010. He also wrote two historical novels, one based on the Chinese civil war and one on Vietnam in 1945 entitled “Fatal Crossroads.”

After their move back to the United States from Berlin in 1966 when Topping was appointed the Times’ foreign editor, the Toppings settled in Scarsdale, New York.

Survivors include his wife, Audrey, and four of their five daughters: Karen Cone, Rebecca (Robin) Topping, Lesley Topping and Joanna Topping. A fifth daughter, Susan Topping, died in 2015.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks