Why did the Titanic sub implode?

Five crew members confirmed to have died in the disaster

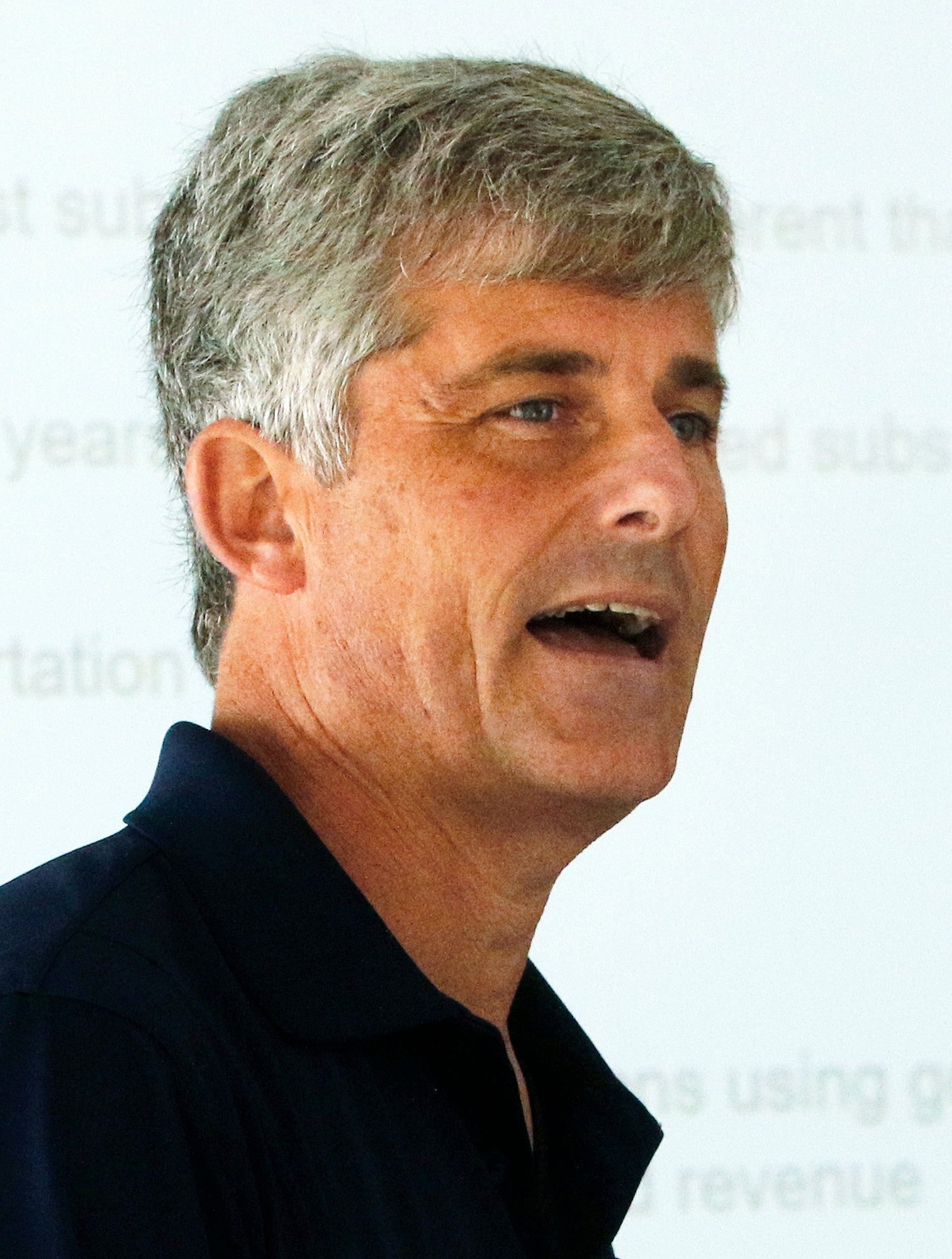

In the days after OceanGate chief executive Stockton Rush and his four-paying crew members went missing on their dive to the wreck of the Titanic, experts had several theories as to their fate.

Perhaps the group had managed to surface and were awaiting rescue amid the Atlantic waves. Perhaps they were trapped underwater within the hull of their broken-down submersible, running out of air.

Or perhaps they had suffered the worst-case scenario: a sudden, catastrophic hull breach, causing their sub to rapidly buckle under the crushing pressure of the water above them.

Follow the latest updates on the missing Titanic sub

On 26 June, those worst fears were confirmed when the US Coast Guard announced that it had found pieces of the Titan submersible scattered across the ocean floor about 1,600 feet from the bow of the ill-fated ocean liner.

But what exactly caused the Titan to implode? While we don’t yet know the truth of what happened, we do know enough to have some idea of what might have sealed the sub’s fate.

An unusual design for a deadly environment

The Titan set off from its mothership, the Polar Prince, on Sunday 18 June, heading for the remains of the Titanic some 3,800 metres below the surface of the ocean. Communications ceased about an hour and 45 minutes later when the sub was probably close to the bottom of its dive.

At that depth, any object – including a human body – is subject to water pressure more than 300 times stronger than the pressure Earth’s atmosphere exerts on us every day. On the surface, we only need to withstand 14.7 lbs per square inch (Psi) of pressure, whereas the Titan had to withstand 5,500 Psi.

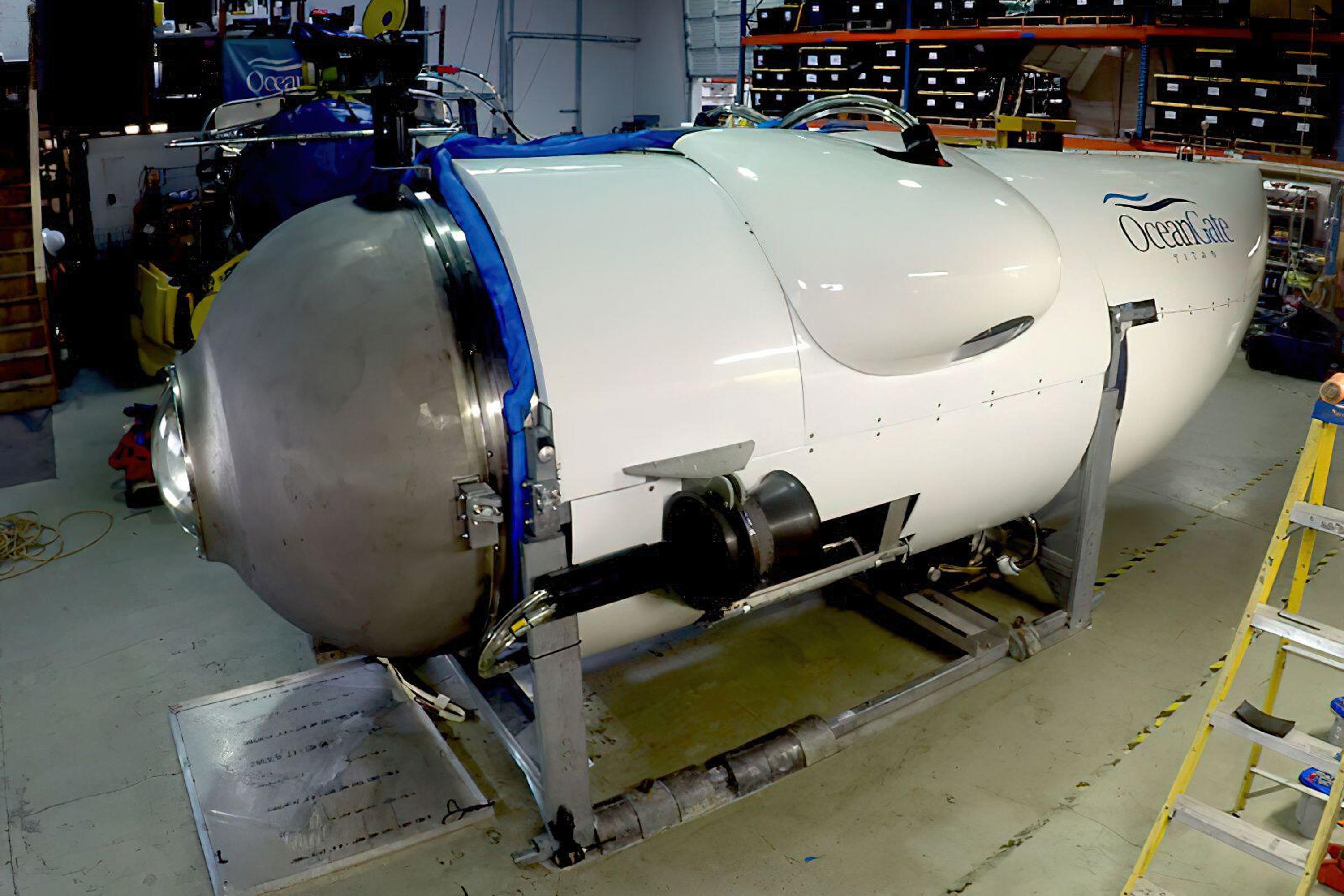

The Titan was designed to survive this level of pressure, with two strong titanium domes at either end of the hull linked by a five-inch-thick cylinder of carbon fibre. According to reports, it was subjected to rigorous safety checks before every dive to make sure there were no defects or faults in the hull.

Carbon fibre is an unusual material for a deep-sea submersible because it is weaker than the solid steel or titanium of which such vessels are usually made. While widely-used in aircraft, it was largely untested in deep-sea diving.

That was a calculated choice by OceanGate founder Stockton Rush, who believed that the material was more viable for such dives than commonly credited.

Unlike metal, carbon fibre is naturally buoyant beyond 2,000 metres, meaning the Titan could be far lighter and cheaper than previous subs.

”You’re remembered for the rules you break,” Rush told YouTuber Alan Estrada in 2021. “I’ve broken some rules to make this. I think I’ve broken them with logic and good engineering behind me.”

To offset this weaker material, the Titan was equipped with a “real-time hull health monitoring system” that could, in theory, detect any deformations, cracks, or other faults rapidly enough for the crew to attempt an emergency ascent.

Yet such depths offer little margin for error. If even one part of the hull fails and lets in water, the pressure would be so great, and the velocity of the incoming liquid so fast, that the sub and its occupants might be torn apart in mere milliseconds, monitoring system or not.

Indeed, a report in The Wall Street Journal suggests that whatever happened to the Titan, happened very fast.

Despite claims that rescuers had picked up “tapping sounds” every 30 minutes, suggesting the crew might still be alive and signalling for help, military insiders told WSJ that a top-secret US Navy system for detecting enemy submarines had heard an implosion soon after the Titan lost communications.

So what might have caused the hull to fail? The answers may lie within a lawsuit filed against OceanGate by one of its most senior former employees.

‘Critical safety concerns’ about the Titan’s hull and porthole

“Now is the time to properly address items that may pose a safety risk to personnel. Verbal communication of [these problems] has been dismissed on several occasions, so I feel now I must make this report so there is an official record in place.”

So wrote OceanGate’s then director of marine operations David Lochridge on 18 January 2018, according to a complaint filed by his lawyers as part of a court battle against the underseas tourism company.

Lochridge had begun working with OceanGate in 2015 and was allegedly tasked with conducting a final safety review of the Titan. His lawsuit, later settled out of court, claimed that he raised “critical safety concerns” about the sub’s “experimental and untested design” – only to be fired for his troubles.

“Issues of quality control with the new submersible were raised, as there were evident flaws throughout the build process,” the lawsuit alleged, noting that no carbon fibre submersible had ever achieved its target depth of 4,000 metres.

It argued that the carbon fibre hull was vulnerable to small defects being widened into “large tears” by the constant changes of pressure, and claimed that “visible flaws” were found in samples of the material produced for the Titan.

Indeed, Mr Rush would later admit to GeekWire after test dives in the Bahamas that the Titan’s hull “showed signs of cyclic fatigue”, meaning it had been stressed by repeated pressure changes. Trips to theTitanic were delayed while these problems were addressed.

Lochridge was also sceptical about the real-time monitoring system, which he believed would only show when a component was very close to failure – perhaps only “milliseconds before an implosion”. The lawsuit alleges that he pressed for the hull to be tested more rigorously but was denied.

Worse, the lawsuit claims that the Titan’s single porthole was only certified to withstand the pressure at 1,300 metres and that OceanGate “refused to pay” for a porthole certified to 4,000 metres.

“Paying passengers would not be aware, and would not be informed, of this experimental design, the lack of non-destructive testing of the hull, or that hazardous flammable materials were being used within the submersible,” the lawyers said.

In its response, OceanGate said that Lochridge “is not an engineer and was not hired or asked to perform engineering services on the Titan.” It said he was fired not for raising safety concerns but for refusing to accept assurances from the company’s lead engineer that its chosen testing methods were better suited to the situation than he believed.

OceanGate told The Associated Press that the missing Titan vessel was finished in 2020-21 - so not the same as the vessel described in Mr Lochridge’s lawsuit.

A ‘rule-breaking’ CEO who refused outside regulation

Mr Lochridge was not the only person concerned about OceanGate’s methods. In 2018, 38 members of the Marine Technology Society’s Manned Underwater Vehicles committee wrote to Stockton Rush expressing “unanimous concern” about the way Titan had been developed.

According to The New York Times, the committee was alarmed that OceanGate had not subjected Titan to a standard risk assessment by Det Norske Veritas (DNV), an international maritime classification body that writes and maintains technical standards for undersea vehicles.

“While this may demand additional time and expense, it is our unanimous view that this validation process by a third party is a critical component in the safeguards that protect all submersible occupants,” the letter said.

OceanGate defended its decision in a 2019 blog post.

“When OceanGate was founded the goal was to pursue the highest reasonable level of innovation in the design and operation of manned submersibles. By definition, innovation is outside of an already accepted system...” the company wrote.

“Bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation.”

And, because the Polar Prince and the Titan operated in international waters, they were not subject to regulation by any country including a US law requiring passenger submersibles to be registered with the Coast Guard.

In the early days of the Toyota Motor Company, engineers were trained to diagnose a problem by repeating the question “Why?” five times.

If a car won’t start, the first “why” might establish that there is a problem with the engine, but the fifth why might reveal that the engine was poorly constructed because its builders were badly trained and underpaid.

Therefore asking why the Titan imploded must eventually lead us to examine Stockton Rush, his attitude to safety, and the nature of OceanGate and its goals.

“There hasn’t been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years. It’s obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations,” Mr Rush told Smithsonian Magazine in 2019. “But it also hasn’t innovated or grown – because they have all these regulations.”

Privately, in response to a letter from an OceanGate consultant imploring him to be more cautious, Rush reportedly said he was “tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation”.

He declared: “We have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often. I take this as a serious personal insult.”

The Titan was not a pure research vessel from a government agency or coalition of universities. It was a commercial vehicle, designed to help OceanGate turn regular Titanic voyages – and, eventually, the exploitation of undersea resources – into a profitable business, and its design followed from that reality.

Already many observers are asking the next set of “whys”, questioning the nature of the adventure industry, the wisdom of the super-rich, and the morality of ferrying paying tourists to perhaps the world’s most famous underwater mass grave.

“I’m struck by the similarity of the Titanic disaster itself, where the captain was repeatedly warned about ice ahead of his ship and yet he steamed at full speed into an ice field on a moonless night,” said James Cameron, the director of the 1999 hit film about the ocean liner, who is also an experienced undersea explorer.

Those questions, however, are harder to answer, and may be debated for just as long as the meaning of the Titanic itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks