Wilder Penfield: Who was he and how did he use burnt toast to map the human brain?

Neuroscientist's work on neural stimulation helped treat epilepsy and illuminated our understanding of phenomena like hallucinations, deja vu and out-of-body experiences

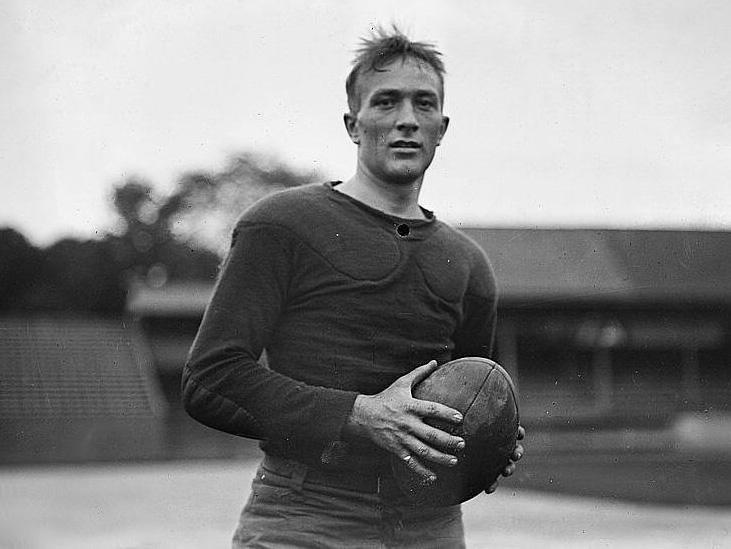

Celebrated neuroscientist Wilder Penfield (1891-1976) is the subject of today's animated Google Doodle on what would have been the 127th anniversary of his birth.

A brilliant man once hailed as "the greatest living Canadian", Penfield is known for developing the Montreal Procedure along with colleague Herbert Jasper in 1950, a treatment for cerebral seizures that destroys troublesome nerve cells by zapping them with electrical probes while the patient is still awake.

More famously, Penfield's experiments with charged stimulation led to his being able to map the brain's sensory and motor cortices and discovering in the process that physical parts of the brain could be teased into evoking memories, like recalling the unmistakeable odour of burnt toast.

This finding enabled Canada to lead the post-war world in neuroscience and healthcare and offer better lives to those suffering with epilepsy. His work also advanced our understanding of such phenomena as hallucinations, illusions and deja vu.

Penfield was actually born in Spokane, Washington, in the US, however. He grew up in Hudson, Wisconsin, before studying at Princeton and earning a Rhodes scholarship to Merton College, Oxford, in 1915. Interrupting his neuropathology studies almost immediately to serve in a French military hospital during the First World War, he was wounded the following year when the SS Sussex was torpedoed.

Returning to Oxford, Penfield married his sweetheart Helen Kermott and returned to the US to study at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, before spells in Boston, New York City and Germany.

From the mid-1920s, Penfield spent his days at the Neurological Institute of New York working on a cure for epilepsy. However, when academic politics saw Rockefeller-funding for a new research institute blocked in 1928, Penfield relocated to Quebec, teaching at the prestigious McGill University and Royal Victoria Hospital before serving as Director of the former's new Montreal Neurological Institute. He became a Canadian citizen in 1934 and went on to achieve the breakthroughs for which he is best known.

The recipient of innumerable honours, Penfield was immortalised by the great science fiction writer Philip K Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), the basis for Ridley Scott's film Blade Runner (1984). Dick used his name for the "Penfield Mood Organ", which allowed his characters to dial up any emotion they wish to feel on demand. His first name was adopted by another dystopian author, J.G. Ballard, for the protagonist of his late novel Super-Cannes (2000), one Wilder Penrose.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments